Archive for the ‘memoir’ Category

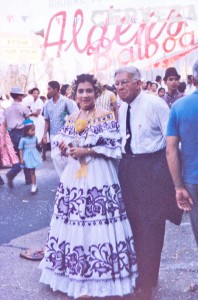

Encountering Carnival in Panama

Panama City, March 1962

I had no idea that we’d arrive in Panama during Carnival. Even as our ship sidled into port at the end of the Pacific crossing, we could hear the sounds of it, the ramshackle city pulsing to a beat like none I’d ever heard. Once docked and allowed to disembark, we passengers pushed our way through dense crowds of people, among which wove decorated floats, costumed dancers, bands crowded onto the beds of battered trucks, men on the street beating drums or, lacking drums, the metal sides of the trucks, all singing and shouting to the heady Latin American rhythms. Sometimes a figure in fantastic costume would pass, surrounded by a group of friends singing and shouting together.

Everyone dresses up for Carnival. I was fascinated to see women wearing the pollera, the Panamanian national costume. Spanish in origin and atmosphere, the dress is of white cambric, embroidered in a bold floral pattern in a contrasting color, usually red, black or blue, each frill trimmed with a border of hand-made lace.

At roadside stalls we watched Panamanian boys scrape blocks of ice for the local sweet. They pressed the ice shavings into a paper cup, and poured over it a bright colored syrup and condensed milk. A bit tasteless, but very refreshing.

Passengers had been warned before we disembarked about the level of crime on Panama’s streets. There’s a hint of bravado in my letter to parents: “You just didn’t go into the side streets, or you would be unlikely to come back alive. Pickpockets everywhere. We were either lucky or careful (or both) but many of the passengers had purses, wallets or cameras stolen.”

What I didn’t write about was the effect on me of the incessant drums, the shouts and snatches of tune, the rhythm syncopated, hypnotic. I wanted to drown in it, swirl with the dancers forever into the glittering ocean of color and sound. But like the hawsers holding the ship to the dock, my past tethered me: syrupy fifties songs about marriage and children, strictures on proper behavior, appropriate dress. We wandered in the crowd for a day, then moved on.

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Scrabble and other equatorial diversions

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

After the storms and seasickness of the first week, we had perfect weather: sunny days, calm seas, and just enough breeze to keep things cool. I decided that ocean voyages were not so bad after all.

I had time to dream. When my husband Tony and I carried our bags up the gangplank of the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” earlier that month, bound for New York and then England, I felt I was walking in the steps of my role model, the great New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, who also went abroad at a young age to pursue a literary career.

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out;

At one stride comes the dark

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

I haven’t played Scrabble in years, and don’t remember what happened to our old game set. But this week we bought ourselves a new one. Nostalgia filled my heart as I pulled out from the bag a handful of little wooden tiles.

JVO photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet, which contains 55 years of letters, notes and memorabilia.

Magical Day on a Tropical Island

I have never returned to Tahiti. I prefer to remember it as it was one special day in February, 1962. When I think of that day, a melody from the musical “South Pacific” fills my head.

I have never returned to Tahiti. I prefer to remember it as it was one special day in February, 1962. When I think of that day, a melody from the musical “South Pacific” fills my head.

In a letter to my parents I described coming in to port: “We got up early in the morning, in time to see us come through the passage between Moorea and Tahiti. Moorea is the most enchanted shape of any island – fantastic contorted peaks rising up out of a faint mist, and shimmering in the morning sunlight. … The sea perfectly calm, glassy inside the reef, and a sparkling sunny day.“ We had plans to explore the island by motor scooter, so after wandering around Pape’ete until we found the rental place, we “followed our noses and found ourselves on the coast road.

In a letter to my parents I described coming in to port: “We got up early in the morning, in time to see us come through the passage between Moorea and Tahiti. Moorea is the most enchanted shape of any island – fantastic contorted peaks rising up out of a faint mist, and shimmering in the morning sunlight. … The sea perfectly calm, glassy inside the reef, and a sparkling sunny day.“ We had plans to explore the island by motor scooter, so after wandering around Pape’ete until we found the rental place, we “followed our noses and found ourselves on the coast road.

“Took a turning up into the hills – very steep, narrow winding road up to a lookout point – excellent view over Pape’ete and out to Moorea. Hibiscus everywhere, vivid red, pink, yellow – any colour you can think of. The vegetation is all a bright yellowish green, and the soil is bright red.

“Coming down – discovered that scooter’s brakes were practically nonexistent – slightly hazardous! Continued along the coast road, looking for somewhere to swim, asking the way in our best French. We were agreeably surprized all day that we could understand and make ourselves understood. Of course they speak much more slowly than the French of Paris – hotter climate.

Found a good beach after a ride down a track through a coconut grove – i.e., very large rough boulders – every so often the scooter would jam and we would have to get off and lift her over. Came out between the houses of two Tahitian families. Fishing nets hung along the beach to dry – used them as a changing tent – not that one would need to worry in Tahiti.  Just wallowed in the lukewarm water – crystal clear, and watched the tiny tropical fish nibbling at our toes. Pretty little things, mostly black and white, though some coloured ones, all spotted and striped. Eavesdropped on the Tahitian families at home – fascinating. A very happy, leisurely people – we were amazed with the genuine friendliness we met everywhere.

Just wallowed in the lukewarm water – crystal clear, and watched the tiny tropical fish nibbling at our toes. Pretty little things, mostly black and white, though some coloured ones, all spotted and striped. Eavesdropped on the Tahitian families at home – fascinating. A very happy, leisurely people – we were amazed with the genuine friendliness we met everywhere.  We saw a fishing canoe come in, manned by six men – and with an outboard motor. Also watched women fishing along the shore – four of them splashing about in their sarongs and laughing and singing as they pulled in the net.”

We saw a fishing canoe come in, manned by six men – and with an outboard motor. Also watched women fishing along the shore – four of them splashing about in their sarongs and laughing and singing as they pulled in the net.”

My letter goes on to describe people-watching at an outdoor café back in Pape’ete: “Easy to pick tourists from the ship – they stood out a mile – the footsore look, paler complexions, brand new plaited straw hats – we got one each too, very fine models for roughly 6/- [about $US 0.42] and were very glad of them all day.” Then an evening visit to a tourist hotel for a display of Tahitian dancing. I commented: “The tourist trade is thriving here, especially since the Americans have just finished making a film here, Mutiny on the Bounty. They have sent prices up. The hotel was one of these places that you know are touristy and a bit artificial, but exciting all the same. Guests sleep in native-style bungalows, and the dance floor was also in native style, with carved supporting poles, thatched roof, and open sides. Dimly lit with coloured lights inside bamboo fish traps. Tables both inside and outside on the grass on the shore of the lagoon – that was where we were. All round the edge, kerosene torches on poles to keep away the insects. A huge full moon shimmering on the water, a jetty to wander out and watch the fish. European dancing (Tahiti version) with floor shows – native dancing. The most exciting dancing I have seen. Fantastically fast hula to the urgent throbbing of native drums. Later in the evening the slower, more graceful hula to drums and singing.

“When the show closed – about 1 a.m., there was a general move toward “La Fayette,” which turned out to be a pretty low dive several miles the other side of Tahiti, and was the most terrific entertainment yet. Dim lights, floor jam-packed – mostly pretty well under the weather. Lots of people from the ship – stewards and passengers, with Tahitian girls. No inhibitions – man, what an education! Got back to the ship about 4 a.m. – shore leave finished at five – and wandered round on the wharf, where women were still sitting patiently at souvenir booths – they had been there all day. Spent our few remaining coins on postcards, etc. Many of the passengers waited up to see the boat out, but we piked and went to bed. Very hard to say goodbye to the place.”

In closing my description of the day, my first in a country other than New Zealand, I wrote: “We found it rather difficult getting used to being tourists – you feel so brash and raw, and totally ignorant, and tolerated by the local population mostly as a useful source of income. I think I would much rather go to a place to live for some length of time – it would give you a much better idea of what it is really like. We were lucky in getting a glimpse of Tahitian families about their ordinary life – that I think was the best part of the whole day. But it was only a tantalising glimpse – enough to whet the appetite.”

In closing my description of the day, my first in a country other than New Zealand, I wrote: “We found it rather difficult getting used to being tourists – you feel so brash and raw, and totally ignorant, and tolerated by the local population mostly as a useful source of income. I think I would much rather go to a place to live for some length of time – it would give you a much better idea of what it is really like. We were lucky in getting a glimpse of Tahitian families about their ordinary life – that I think was the best part of the whole day. But it was only a tantalising glimpse – enough to whet the appetite.”

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Hurricane at Sea

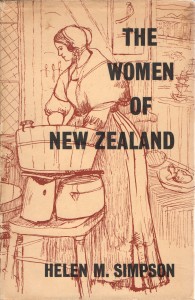

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

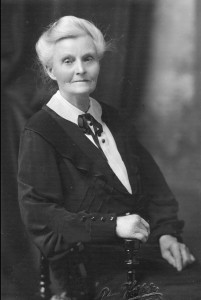

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

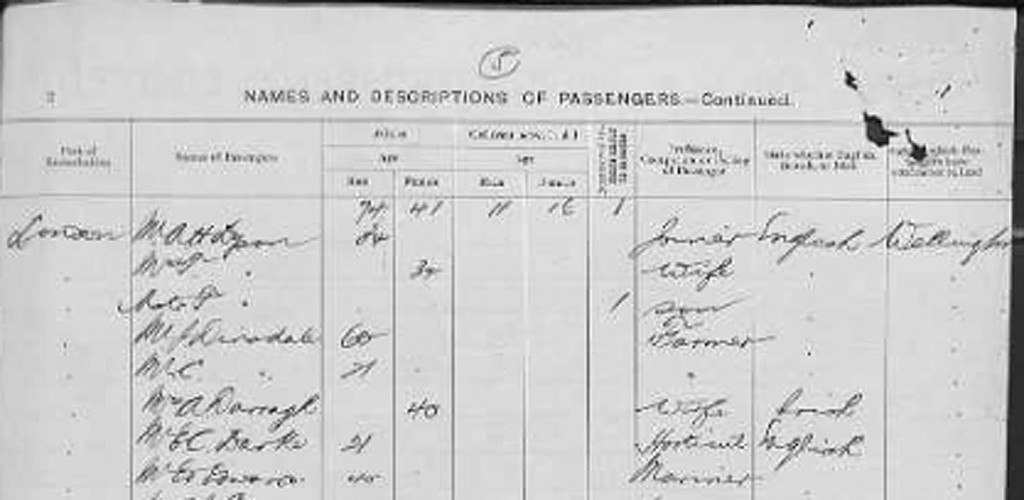

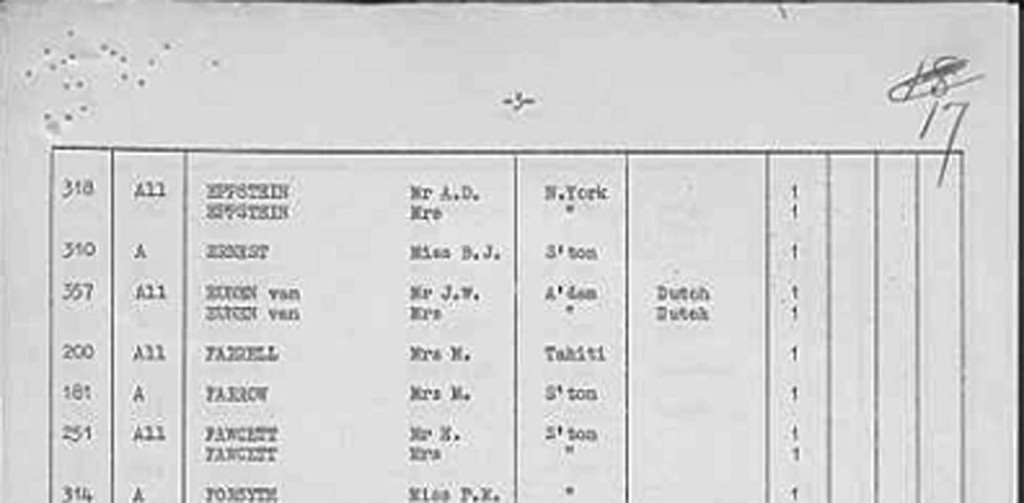

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

As Godwits Fly

Godwits landing on the Motueka, NZ sandspit after their migration from Alaska.

Image from http://blog.doc.govt.nz/tag/motueka/

When asked why so many of us travel abroad, most Kiwis will respond that our birth country is a long way from anywhere and we want to see what the rest of the world looks like. The iconic image for such a journey is the godwit, a mottled brown wading bird with a long upturned bill that arrives around mid-September and spends the New Zealand summers foraging in mudflats and marshes. As the southern hemisphere air turns autumnal, godwits flock on sand spits and set off on their annual migration to another summer. They fly non-stop, nine thousand miles north to their breeding grounds in Alaska and Siberia. The mysterious compulsion for this incredible journey captured the imagination of early New Zealand writers.  Robin Hyde, in her 1938 novel The Godwits Fly, first offered the metaphor: Most of us here are human godwits; our north is mostly England. Our youth, our best, our intelligent, brave and beautiful, must make the long migration, under a compulsion they hardly understand.

Robin Hyde, in her 1938 novel The Godwits Fly, first offered the metaphor: Most of us here are human godwits; our north is mostly England. Our youth, our best, our intelligent, brave and beautiful, must make the long migration, under a compulsion they hardly understand.

A decade later, the poet Charles Brasch would write:

Remindingly beside the quays the white

Ships lie smoking; and from their haunted bay

The godwits vanish towards another summer.

Everywhere in light and calm the murmuring

Shadow of departure …

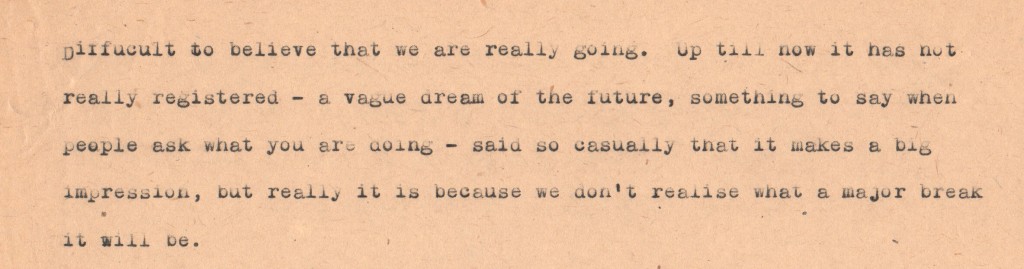

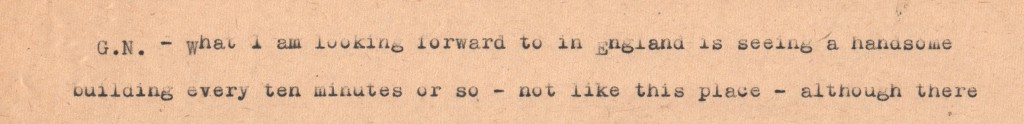

Among my notes in my black filing cabinet is something I must have typed not long before my husband Tony and I left for England:

Pinned to that sheet of 9×6” newsprint (which we reporters used at The Press to type up our stories) is another with this comment from a friend:

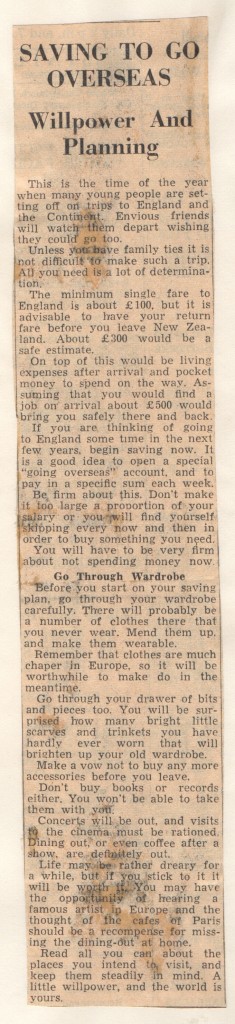

And in my clippings from The Press scrapbook is this advice column. The savings amounts I suggested are in New Zealand pounds, which were each worth US $1.40 in 1961. Even for the time, they were wildly optimistic, as we discovered when we arrived in London.

And in my clippings from The Press scrapbook is this advice column. The savings amounts I suggested are in New Zealand pounds, which were each worth US $1.40 in 1961. Even for the time, they were wildly optimistic, as we discovered when we arrived in London.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Inside a 1960s newspaper office

In graduate seminar at the University of Canterbury, Professor Neville Phillips fixed me with a stern eye as he returned my latest effort. “You are getting through your history papers, Miss Dinsdale, on your writing style, not on your knowledge of history.” I flinched, and worried. Graduation was coming up, and I planned to apply for a job on The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. Within the next week or two I needed to ask him for a letter of reference. Not only was Prof. Phillips head of the history department, he was a former newspaperman himself, and still had deep connections at The Press.

I needn’t have worried. Not only did he write me a nice reference, he also penned a personal note to the paper’s editor, Arthur Rolleston (Rollie) Cant, that opened the door to my dream job.

Press Building, Cathedral Square, Christchurch, NZ. Photo by Michael Whitehead from

http://www.nzine.co.nz/features/150years_the_press.html

I had known since childhood that writing was what I wanted to do. Movies about newspapers such as While the City Sleeps (1958), Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) and Ace in the Hole (1951) filled me with fantasies about the drama and excitement of the reporter’s life. Here was my chance to prove myself.

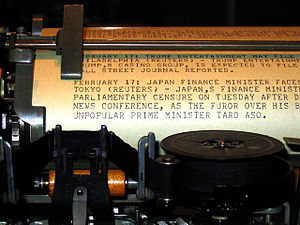

I loved working at The Press. A great Gothic pile on Cathedral Square, in the heart of Christchurch, the Press Building was a newspaper office out of one of those Hollywood movies: a cavernous newsroom that smelled of newsprint and dust, where telephones jangled, the chief reporter barked commands and the urgent clatter of the Teletype machine signaled a breaking story somewhere in the world.

Picture of Merganthaler linotype machines in a compositing room from the archives of the Nieman Foundation http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/

Sometimes I would be sent on an errand out back to the compositing room, a shadowy cave where enormous Mergenthaler Linotype machines made a deafening clatter. Deeper into the heart of the building, the throb and rumble of the great press itself, and the bustle of loading trucks in the small hours of the morning for long distance runs. When The Press celebrated its 100th anniversary in May 1961, its circulation was 62,000, with subscribers throughout the South Island.

It felt glamorous to work late into the evening, rushing back from meetings to meet the deadline for next morning’s paper. I shared dreams with the other young reporters, all of us with a few scratched notes tucked away for what each of us was sure would be the Great New Zealand Novel. We all had the sense of being part of an old tradition.

Among my notes I found this description of the office, written in 1960. Christchurch at that time was a sleepy provincial city of 193,000 people, and exciting news stories didn’t happen all that often.

I described the office as a jumbly assortment of rooms, all dirty and uncared for, and with space saving nonexistent.

I particularly appreciated my desk in the women’s department, by a window where I could gaze out across Cathedral Square. I’ve written about this view in an earlier post.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Given Time

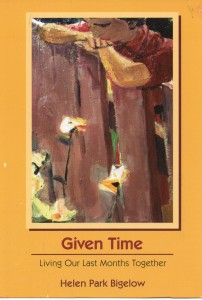

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

To offer a flavor of the book, I can’t do better than to quote the blurb by Fithian Press, the book’s publisher: “The book deals honestly with the process of dying, an ordeal shared by both of them. It also deals with the process of staying alive and in love until the ordeal is over… [Bigelow] writes with brutal honesty about her anger and grief over what has become of her husband and herself. The book isn’t a manual about how to take care of a dying man, but it makes the reader well aware of what a grueling job it is. “So this is it,” she writes. ‘This chemo routine is the rest of our lives together…and goddamn it, it’s going to be as good for both of us as I can make it.’ ”

Reading this book set me to thinking about my husband’s and my circle of friends. We’re all of an age where we’re facing mortality, both our own and our partners’. Physical infirmities creep up on us. Memories start to fail. The mechanisms of the heart become clogged. I know we’ll all do what we have to do, to the best of our abilities, when loved ones need our care, and that, if we are the ones whose lives are ending, we hope to have someone as caring as Helen to tend our passage. I’m grateful that services such as hospice are available. Most of all, I am inspired by Helen’s love of beauty to seek it out in my own life. Whether my time is counted in decades or years or even months, I want every day to be touched by grace.

Ending a Story

I’ve just posted a piece on the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference blog about working with my editor, Andrew Todhunter, on revisions to my memoir about my sister Evelyn. The draft is finished, and out once again for comments. It’s always so valuable to see one’s work through another’s eyes.

Now I’ll need to write an epilogue. Just this week we learned that the New Zealand Geographical Board has assigned the name Stokes Peak, in Evelyn’s honor, to a peak in the Kaimai Range, between Tauranga (where she was born) and the Waikato (where she lived and worked). An impressive end to the story.