Posts Tagged ‘New Zealand’

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

Inside a 1960s newspaper office

In graduate seminar at the University of Canterbury, Professor Neville Phillips fixed me with a stern eye as he returned my latest effort. “You are getting through your history papers, Miss Dinsdale, on your writing style, not on your knowledge of history.” I flinched, and worried. Graduation was coming up, and I planned to apply for a job on The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. Within the next week or two I needed to ask him for a letter of reference. Not only was Prof. Phillips head of the history department, he was a former newspaperman himself, and still had deep connections at The Press.

I needn’t have worried. Not only did he write me a nice reference, he also penned a personal note to the paper’s editor, Arthur Rolleston (Rollie) Cant, that opened the door to my dream job.

Press Building, Cathedral Square, Christchurch, NZ. Photo by Michael Whitehead from

http://www.nzine.co.nz/features/150years_the_press.html

I had known since childhood that writing was what I wanted to do. Movies about newspapers such as While the City Sleeps (1958), Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) and Ace in the Hole (1951) filled me with fantasies about the drama and excitement of the reporter’s life. Here was my chance to prove myself.

I loved working at The Press. A great Gothic pile on Cathedral Square, in the heart of Christchurch, the Press Building was a newspaper office out of one of those Hollywood movies: a cavernous newsroom that smelled of newsprint and dust, where telephones jangled, the chief reporter barked commands and the urgent clatter of the Teletype machine signaled a breaking story somewhere in the world.

Picture of Merganthaler linotype machines in a compositing room from the archives of the Nieman Foundation http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/

Sometimes I would be sent on an errand out back to the compositing room, a shadowy cave where enormous Mergenthaler Linotype machines made a deafening clatter. Deeper into the heart of the building, the throb and rumble of the great press itself, and the bustle of loading trucks in the small hours of the morning for long distance runs. When The Press celebrated its 100th anniversary in May 1961, its circulation was 62,000, with subscribers throughout the South Island.

It felt glamorous to work late into the evening, rushing back from meetings to meet the deadline for next morning’s paper. I shared dreams with the other young reporters, all of us with a few scratched notes tucked away for what each of us was sure would be the Great New Zealand Novel. We all had the sense of being part of an old tradition.

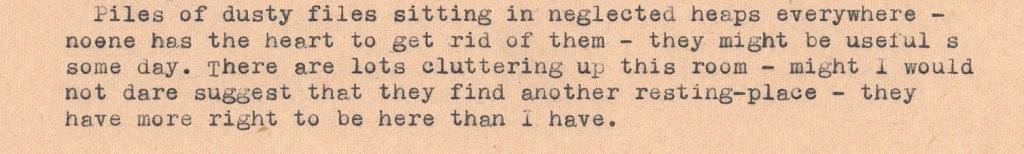

Among my notes I found this description of the office, written in 1960. Christchurch at that time was a sleepy provincial city of 193,000 people, and exciting news stories didn’t happen all that often.

I described the office as a jumbly assortment of rooms, all dirty and uncared for, and with space saving nonexistent.

I particularly appreciated my desk in the women’s department, by a window where I could gaze out across Cathedral Square. I’ve written about this view in an earlier post.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Women’s Lives in 1960s New Zealand

New Zealand social mores were clear when I was growing up in the 1940s and ‘50s: a woman’s place was in the home, taking care of husband and children. A few women (like my mother-in-law) worked after they had children, but the job options were few.

The staff at Christchurch’s The Press newspaper was overwhelmingly male. When I started in 1960, there was only one other woman reporter, besides myself, in the general reporting pool. A vacancy occurred in the Women’s Department, secluded in a separate little office down the hall. The other woman reporter, older and wiser about gender issues, adamantly refused to take it. I didn’t want to go either. I was having a ball scouring the big city hotels for interesting overseas visitors, interviewing artists, musicians and others with fascinating careers and histories. But I was not given a choice. Fortunately the women’s page editor, Tui Thomas, was sympathetic to my lack of interest in fashion and the social scene, and set me to reporting on meetings of various organizations focused on women and families.

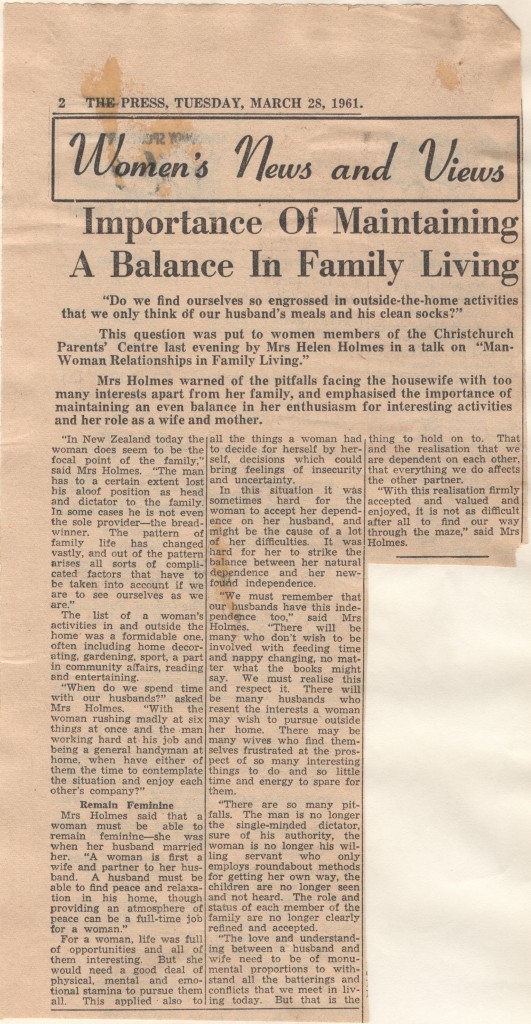

I cringed when I first re-read this clipping from my scrapbook, with its sexist stereotypes. Looking more carefully, I sense the speaker’s unease. By the early 1960s, change was in the air. I don’t remember who Mrs Holmes was, but I imagine her as an older woman struggling to reconcile traditional values with the emerging demand by a younger generation of women for an expanded role in the world outside the home. I’ve appended a transcription, in case you have trouble reading the old newsprint.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The Press, March 28, 1961 (transcription)

Importance of Maintaining a Balance in Family Life

“Do we find ourselves so engrossed in outside-the-home activities that we only think of our husband’s meals and his clean socks?”

This question was put to women members of the Christchurch Parents’ Centre last evening by Mrs Helen Holmes in a talk on “Man-Woman Relationships in Family Living.”

Mrs Holmes warned of the pitfalls facing the housewife with too many interests apart from her family, and emphasized the importance of maintaining an even balance in her enthusiasm for interesting activities and her role as a wife and mother.

“In New Zealand today the woman does seem to be the focal point of the family,” said Mrs Holmes. “The man has to a certain extent lost his aloof position as head and dictator to the family. In some cases he is not even the sole provider—the breadwinner. The pattern of family life has changed vastly, and out of the pattern arises all sorts of complicated factors that have to be taken into account if we are to see ourselves as we are.”

The list of a woman’s activities in and outside the home was a formidable one, often including home decorating, gardening, sport, a part in community affairs, reading and entertaining.

“When do we spend time with our husbands?” asked Mrs Homes. “With the woman rushing madly at six things at once and the man working hard at his job and being a general handyman at home, when have either of them the time to contemplate the situation and enjoy each other’s company?”

Mrs Holmes said that a woman must be able to remain feminine—as she was when her husband married her. “A woman is first a wife and partner to her husband. A husband must be able to find peace and relaxation in his home, though providing an atmosphere of peace can be a full-time job for a woman.”

For a woman, life was full of opportunities and all of them interesting. But she would need a good deal of physical, mental and emotional stamina to pursue them all. This applied also to all the things a woman had to decide for herself, by herself, decisions which could bring feelings of insecurity and uncertainty.

In this situation, it was sometimes hard for the woman to accept her dependence on her husband, and might be the cause of a lot of her difficulties. It was hard for her to strike the balance between her natural dependence and her new-found independence.

“We must remember that our husbands have this independence too,” said Mrs Holmes. “There will be many who don’t wish to be involved with feeding time and nappy changing, no matter what the books might say. We must realize this and respect it. There will be many husbands who resent the interests a woman may wish to pursue outside her home. there may be many wives who find themselves frustrated at the prospect of so many interesting things to do and so little time and energy to spare for them.

“There are so many pitfalls. The man is no longer the single-minded dictator, sure of his authority, the woman is no longer his willing servant who only employs roundabout methods for getting her own way, the children are no longer seen and not heard. The role and status of each member of the family are no longer clearly defined and accepted.

At Gallipoli

The Anzac Day memory floats up from my childhood: gray dawn in a small New Zealand town, plod and shuffle of marching feet, old men in uniforms button-stretched across their chests. The oldest of the veterans lays a wreath at the foot of a cenotaph where names are inscribed: casualties of the First World War.

When the war started in 1914, New Zealand was a British colony of less than a million people. Eager to come to the aid of the mother country in her time of need, more than 100,000 men signed up, and well over half of these were killed or wounded. A place name that crops up often on the marble tablets of small New Zealand towns is Gallipoli, Turkey. Seeking to take Constantinople, Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty, sent the Australia and New Zealand Expeditionary Force (the ANZACs) to storm the Gallipoli Peninsula, which overlooks the Dardanelles, a channel connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. Writing in Slate, journalist Andrew Curry comments: “Though Gallipoli was a small conflict compared with landmark battles of the first world war like the Somme, the battle for the narrow peninsula contains the story of the war in microcosm: the fatal bravado, the futile fighting, the error-prone assumptions made by politicians and generals, and the killing fields that decimated a generation of young men.”

At dawn on April 25, 1915, the ANZACs landed at a small cove surrounded by steep cliffs. They met stiff resistance from Turkish troops. For nearly nine months the two sides fought and died, until finally the ANZACs withdrew. The website for the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage comments: “It may have led to a military defeat, but for many New Zealanders then and since, the Gallipoli landings meant the beginning of something else – a feeling that New Zealand had a role as a distinct nation, even as it fought on the other side of the world in the name of the British Empire.”

The rugged landscape of the peninsula is now a Turkish national park, filled with cemeteries and monuments to the dead of both sides. I was there last week, almost ninety-nine years after that tragic venture. At every memorial site, huge semi-circles of temporary bleachers were being set up for the Anzac Day ceremonies, which will be attended on April 25 by tens of thousands of Turks, Australians and New Zealanders.

With us also at Gallipoli last week was a group of New Zealand high school students. We had met them the previous day in Troy where, in the shadow of a modern Trojan Horse sculpture, and with “ancient Greek” costumes rented from a nearby stall, they were having an exuberantly good time re-enacting battle scenes from Homer’s Iliad.

This day at Anzac Cove the mood was markedly different. With solemn steps the students inspected the graves, where the ages of the dead were little different from their own: seventeen, eighteen, twenty-four. One young man passed out red lapel poppies to visitors, including our American tour group. We watched as one by one the students approached the cenotaph, placed their poppy at its base, and stood a moment with bowed head.

A New Zealander by birth, I have not lived in my home country for fifty years. Nevertheless, that day of pilgrimage I carried with me a small New Zealand flag. Following the students’ example, I attached my poppy to the flag and placed them both in the drift of red poppy emblems that lay like fallen petals at the cenotaph’s base. I thought of the stories from Gallipoli of Turkish and ANZAC soldiers who bombed each other by day and in the evening shared cigarettes and rations and helped tend each other’s wounded. I thought of the kindness of our Turkish tour guide who reorganized the tour schedule so that my husband and I could visit the New Zealand memorial site. I thought of the words of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who led the Turkish troops, and later went on to become the founder of the Turkish Republic. They are engraved in stone at Gallipoli:

Those heroes that shed their blood

And lost their lives.

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore, rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies

And the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side

Here in this country of ours,

You, the mothers,

Who sent their sons from far away countries

Wipe away your tears,

Your sons are now lying in our bosom

And are in peace

After having lost their lives on this land they have

Become our sons as well.

Anniversary of a Departure

Fifty years ago today, my husband Tony and I said farewell to family on the quay in Wellington, New Zealand, and walked up the gangplank of the ocean liner Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt, drawn by that migratory urge young New Zealanders have to explore the other side of the world. This poem says a little about how it felt.

LEAVING NEW ZEALAND

I am Katherine Mansfield come again

on that slow ship out of Wellington.

Taste of bile in my mouth, I endure

the airless heat of the lower decks

rank with galley smells

and the deep-throated thump of engines.

The ice-slick of my daughter’s death

stumbling my speech,

I sit with parties playing Scrabble on the deck

where Indonesian stewards in white jackets

rattle tea-trolleys.

Evenings, I watch for that streak of light

as sun plunges into viscous sea.

Then sudden dark.

Familiar stars of my Antipodes

recede southward.

In their place, carved mahogany panels

that fill the walls of staterooms and stairways:

solemn eyes of strange beasts

peer from behind carved vines,

birds in extravagant plumage

perch on the edge of my dreams.

A Lifetime of Friendship

“I have not written these poems, nor even read them; this is a spoken book,” declares my friend Diana Neutze on the back cover of her latest collection, AGAINST ALL ODDS. The title refers not just to her illness—she has battled Multiple Sclerosis for well over forty years—but to the difficulties inherent in transforming poems from her mind to the printed page. As MS closed down her body, she progressed from longhand, to one finger on the computer, to voice recognition. “But now I dictate to Gabrielle, my editing carer. Even the editing has been done by voice, backwards and forwards in the air.”

I was privileged to receive a copy of this handsome limited edition. Written over the past three years, the poems chronicle the poet’s recognition that her death is imminent and her determination to live each remaining day in the beauty of the moment. The poems are rich with images such as: …a tangle of branches/ peremptory against a crystal sky. She asks:

If I died tomorrow, what would

happen to the poems in my head?

Christchurch, New Zealand, where Diana lives, has suffered a series of devastating earthquakes and aftershocks that figure in many of the poems. In “Elsewhere” she writes:

…the earth where I thought

to lay my final bones

is writhing like a wounded snake.

The earthquake draws her mind outward to share a communal grief:

I mourn for the lost, the mained, the dead.

I mourn for our grieving city.

The experience of working with composer Anthony Ritchie on a song sycle of her poems draws her to a new awareness of the importance of people in her life. The final poem in the book reworks “Goodbye,” the final poem in the song cycle. Keeping the opening lines: If this day were to be/ my last …, she traces the trajectory of her preparations for death, from spiritual and inward-looking to a recognition of a fear in which …I relegated/ my friends to the outer suburbs. The poem ends:

If tonight were to be my very last,

I would be desolate

at leaving behind

a lifetime of friends.

I have been friends with Diana since our freshman year at the University of Canterbury, fifty-four years ago, where we met in English Literature class. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate parents of small children in London. Over the years and across the globe we have stayed in touch, supporting each other as best we could in times of grief, commenting on each other’s poems, occasionally visiting. I honor this lifetime of friendship as I read AGAINST ALL ODDS.

Ending a Story

I’ve just posted a piece on the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference blog about working with my editor, Andrew Todhunter, on revisions to my memoir about my sister Evelyn. The draft is finished, and out once again for comments. It’s always so valuable to see one’s work through another’s eyes.

Now I’ll need to write an epilogue. Just this week we learned that the New Zealand Geographical Board has assigned the name Stokes Peak, in Evelyn’s honor, to a peak in the Kaimai Range, between Tauranga (where she was born) and the Waikato (where she lived and worked). An impressive end to the story.

Catching my breath

Countdown to the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, which starts next Thursday, July 29. Amazingly, I’m caught up for the moment on co-director tasks. Time to take a deep, relaxing breath and think about the wealth of wildlife with which this place is blessed. Last evening, on the hill behind our house, we saw our first California gray fox of the season. A cottontail scampered out of sight as a pair of angry scrub jays attacked the fox. Later, the stags emerged, two of them, both with magnificent six-point racks of antlers. We’ve been watching the new season’s fawns gradually lose their spots. A jack rabbit family shares the front garden with the quail family. Hummingbirds and bees have discovered an exotic treasure from my native New Zealand: a young Metrosideros excelsus. It is commonly known as New Zealand Christmas Tree because on the northern coast of New Zealand its spectacular clusters of red flowers bloom in December. Here on the other side of the world, where summer is on the other side of the calendar, it has been brightening our gray July. We call it by its Maori name, Pohutukawa.

Natives and Exotics

My friend Diana, who lives in New Zealand, has a wonderful piece in her journal today about the “exotic” species in her garden. It set me thinking about where I live. The English sparrows and starlings that forage in town don’t have much chance here at the edge of the forest, where the native birds are so dominant. Our resident Red-Shouldered Hawk argues noisily with the ravens, an American Robin sings his heart out from the top of the tallest fir. A dozen quail putter through the garden, and the returning Violet-Green Swallows inspect their nest site in the porch.

Of plants my garden is a mixture: some natives, but more Mediterranean and Australian dry-summer species. My little apple tree is in glorious blossom. But the tree I treasure is a young and flourishing Pohutukawa, a New Zealand native that reminds me of the beaches of my childhood.

Strip-mining New Zealand’s National Parks?

A disturbing mailing from my homeland. It seems the New Zealand government is considering a proposal to allow mining in some of the country’s high-value conservation land. Environmental organizations are horrified. Forest & Bird, one of the country’s major environmental organizations, noted in its online article:

Mining in any of these presently protected areas will further imperil our threatened species, destroy important habitat and leave us with contaminated waterways, scarred landscapes, subsidence and erosion problems and an almighty clean-up bill from ‘orphaned mines’.

Moreover, it will severely tarnish New Zealand’s ‘clean, green’ image.

The New Zealand Government has called for submissions from the public on its mining proposals. Submissions close at 5 pm (NZ time) on Tuesday, 4 May 2010. If you have visited New Zealand and seen what could be destroyed by mining, I urge you to learn more from Forest & Bird and other New Zealand environmental organization sites, and submit a protest. A good site for an overview of protest activity is 2precious2mine.