Archive for the ‘history’ Category

The Easter Bunny mystery

How could my husband and I be so mean as to deny our kids the Easter Bunny? I frowned as I reread the letter to my parents stashed in my old black filing cabinet.

12 April 1971

The kids are back at school today after their week of Easter vacation. The weather has been so beautiful and spring-like. This is something I couldn’t really understand until I came to the northern hemisphere—the significance of Easter as a spring festival—the death and rebirth of the god that is an important part of almost every religion there has ever been. Here a big thing at Easter is the Easter Bunny, who is alleged to bring baskets of candy eggs and goodies to kids on Sunday morning. This Tony and I just can’t go along with—somewhat to the kids’ disappointment, I think, though we do buy them a fancy Easter egg, and of course we have the fun and mess of dyeing hard-boiled eggs and hiding them in the garden for an egg hunt. I did allow Simon to share our pet rabbit at school one morning. Bun-Bun was less than enthusiastic about the whole project, but the children were ecstatic.

Part of the reason for our rejection of the Easter Bunny was that Tony and I grew up in New Zealand, where rabbits were despised as pests. Brought by early settlers to a place with no natural predators, their population quickly reached plague proportions, causing major erosion problems. We did have Easter eggs, but given that we celebrated the festival in the Southern Hemisphere autumn, they had no significance other than as a source of sugar and chocolate. Even living in California, we couldn’t see any connection between rabbits and the Christian celebration of the Resurrection. I decided this week to look into the question. I quickly found myself down a fascinating rabbit hole of customs, beliefs, and theories, many of them contradictory.

How the Easter Bunny came to the U.S. seems pretty clear. According to several sources, the creature first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” who brought colored eggs to good children at Easter. As the custom spread across the U.S. the hare somehow transformed itself into the more familiar rabbit and its Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts.

The hare’s (or rabbit’s) connection with Christianity are more complicated. For the first few centuries, the Christian festival coincided with the Jewish Passover, which is when the historical events surrounding Jesus’s death occurred. Though the Christian calendar has since been modified, both festivals are still close to each other in spring. Both are based on a lunar calendar; the date of Easter was defined in 325 CE by the Council of Nicaea as the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. In Anglo-Saxon regions of Northern Europe, the Christian festival seems to have merged with a pre-existing equinox festival honoring Eostre, the goddess of spring, and Christians continued to use the name of the goddess to designate the season. Since hares and rabbits give birth to large litters in early spring, they have long been recognized as symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the vernal equinox.

No, no, no, say some Catholic writers. The Easter Bunny has Christian origins. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that the hare could conceive again while pregnant, thus shortening the time between litters and delivering more offspring during a breeding season. Later Greek writers such as Pliny and Plutarch expounded the notion that hares (and rabbits, by association) were hermaphrodite, and thus could self-impregnate and reproduce as virgins. During the medieval period, hares and rabbits began appearing in illuminated manuscripts and paintings depicting the Virgin Mary, serving as an allegorical illustration of her virginity.

Two pregnancies at once? Intrigued, I veer into another passageway of my research rabbit warren. It turns out that, as the Smithsonian Magazine put it, “Aristotle got it right: the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) can get pregnant while it’s pregnant.” In 2010, scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, Germany, led by Dr. Kathleen Roellig, published the results of their study. Using selective breeding and high-resolution ultrasonography, they showed that a male hare can fertilize a female during late pregnancy. The resulting embryos will develop around four days before delivery of the first pregnancy. To quote from the Smithsonian article: “The embryos don’t have any place to go at that time, however, since the uterus is occupied by the embryos’ older brothers and sisters. So the embryos hang out in the oviduct, rather like when you wait in your car for a parking space to open up. Once the uterus is free, the embryos move in.”

My head is spinning. I think I need chocolate.

Community battles housing discrimination

In the early 1970s, my husband and I volunteered with Mid-Peninsula Citizens for Fair Housing. Here’s an article about the organization I wrote for my Christchurch, New Zealand paper.

FAIR HOUSING: A COMMUNITY APPROACH

Cupertino, CA, 1972

Discrimination in housing on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin has been illegal in the United States since 1968. But it is not so easy to legislate away prejudices so deeply ingrained that they are written into the textbooks of realtors and enshrined in the housing patterns of all our communities.

One group that has found this out the hard way is a San Francisco Peninsula organization called Mid-Peninsula Citizens for Fair Housing. Committed to the right of all persons to purchase or rent property wherever they choose, MCFH evolved in 1965 out of a nucleus of citizens who had fought an election proposition that would write in to the California constitution the right of the housing industry to perpetuate the existing discriminatory housing patterns.

The proposition passed, and MCFH learned its first lesson, that even in this allegedly liberal area, the housing market was tight shut.

Education, they concluded, was the key. By the time the federal Civil Rights Act of 1968 outlawed all measures like Proposition 14, MCFH had speakers visiting schools, factories and church meetings. Representatives started talking with local government officials and housing developers, focusing attention on the problems of housing for the aged, and other low income groups, as well as on racial minorities. A full-time lobbyist was employed to keep in touch with elected representatives in Sacramento, the state capital.

With the legal clout of the 1968 Act, they set up a legal aid service for members of minority groups discriminated against in obtaining housing. When a complaint is received, the Fair Housing Office sends out a White volunteer checker. In order to eliminate other legitimate grounds for a landlord to refuse an apartment, the checker matches the complainant as closely as possible, in everything except race.

The availability of the home, and the terms offered, are compared. If discrimination is apparent, MCFH offers the services of a volunteer lawyer, or assistance in filing a complaint with HUD.

But still this was not enough. Blacks and Chicanos, seeing the organization as yet another example of white liberal condescension, have been reluctant to contact the Fair Housing Office. On current showing it is affecting only one percent of the apartments in the area each year, and even fewer of the real estate sales. Meanwhile Peninsula communities are becoming more and more segregated, in terms of race, age, and economic status.

Now MCFH has added a new weapon to its arsenal. It is the community audit, a technique designed by Howard Lewis, a local realtor and vice-president of MCFH. The method used for an audit is much the same as that used to check individual complaints. The difference is that it is done by people already living in the neighborhood, who see their effort as a contribution to the community as a whole, and not to their individual housing needs.

Teams of checkers are made up: one White, one of a minority race. Most of the audits so far have been White/Black, but some White/Chicano audits are getting under way. One after the other the team members apply to their assigned apartments, and report back on the terms offered to them. The results are frequently double-checked, cautious MCFH lawyers preferring to give apartment managers the benefit of the doubt in dubious cases. But eventually a profile of the city’s housing practices emerges: in so many cases the Black was told that nothing was available, but the White was invited right in; in so many cases the rent quoted to the Black was higher, or the cleaning deposit was larger, or the credit check would take longer. The figures run between fifty percent and sixty percent for most of the varieties of discrimination, and the overall figure has been as high as seventy percent of the apartment units in any one city.

Reports are made to the individual apartment managers and owners, complimenting those who were shown to be obeying the law, seeking consultation with those who don’t. “The very least a fair housing organization can do,” says Fair Housing Director Marilyn Nyborg, “is contact housing industry members and talk with them—to deal with their fears, inform them of the law, and seek their commitment to equal opportunity in housing.”

The audits are repeated quarterly, and MCFH is prepared to take legal action against persistent offenders. But its members feel that local pressure is a more satisfactory incentive for obeying the law. For this reason the city council and the local press are also informed of the results of the survey.

Some city councils have reacted with suspicion and hostility; others have been spurred to initiate positive programs for their city’s housing needs. The City of Palo Alto, for instance, has set up meetings between discriminating apartment owners, representatives of MCFH, and its own Human Relations Commission; has agreed to act as co-plaintiff in discrimination cases; and has given notice, through a mailing to its utilities customers, that fair housing laws will be enforced in the city. Under discussion are ordinances that would provide for a public vacancy list; for the licensing of apartment managers; and for the use of written records of the terms offered to every prospective tenant. These stricter regulations are necessary, MCFH claims, because the education sessions they already provide for apartment managers have had little effect on their attitudes or practices.

We can influence the quality of life in our own communities, says MCFH. And change, though painfully slow, is happening. A few housing developers have publicly committed themselves to equal opportunity in housing. Some local realtors now display fair housing pledges in their windows. Membership of MCFH has swelled from the original handful of people to well over 2,000, and the annual operating budget, including contributions from local industries, is over $17,000. The organization is still a long way from its ultimate goal, equal justice for all in the housing market. But it is on its way.

The other side of the freeway

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a battered cardboard box containing the manuscript of a novel I wrote in the early 1970s. I understand now why it never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject: racial discrimination in housing. As I reread some of the text, I recalled the shock I felt when I first grasped the magnitude of the social gaps. The descriptions that follow come from my own experience as I researched the book, and it began my involvement with the fair housing movement.

Here is the central character Karen, a newspaper reporter, visiting the black ghetto of East Palo Alto for the first time to interview the director of a community advice center:

She knew vaguely that East Palo Alto belonged to the county. … She crossed the county line now, and accelerated to get onto the overpass that spanned the freeway. As she came down the ramp on the other side, she knew she was in a different country. The road was suddenly pot-holed and bumpy, and brown dust rose in thick choking swirls from its verges. She slowed, and looked about her. Such tiny bedraggled houses, desperately in need of paint. Yards littered with junk, yet here and there a brave attempt at order and color, a flower-bed, a well-cut lawn. She came upon a few tatty shops. Surely this couldn’t be the main shopping center? Yet soon she could see the sign, NAIROBI SHOPPING CENTER, and underneath, in a language she could not understand, UHURU NA UMOJA.

She had to force herself to open the door. Lurid accounts of rapes and muggings and violence in the streets flooded her mind. Here she was the enemy. She wanted to jump back into the car and get out, away from this place.

A woman passed, with two small children, headed for the market. She looked indifferently at Karen as she passed, then turned to scold one of the children, who was whining for candy. Karen let out the breath she had been involuntarily holding, and made herself move on. … Across the road, outside a liquor store, a black knot of middle-aged men stood transfixed in time, waiting for nothing.

It was hot. The dust lifted lazily as she walked. Something about the huge trees, and the stillness of the air, brought to her mind descriptions she had read of towns in the southern states. But this was California. It did not make sense. A mockingbird flashed its wings across her path, still proudly singing.

Karen does her interview, in which she learns about the pressures of living in East Palo Alto (and also finds herself attracted to Paul, the advice center director).

She said goodbye, and walked slowly back to the car, past the Louisiana Soul Food Kitchen and the Black and Tan Barber. The heat and dust were almost unbearable.

Back across the freeway, she noticed for the first time the neatly swinging redwood sign: Welcome to Palo Alto. A few blocks further down University Avenue and it hit her like a punch in the gut. She pulled over to the side of the road and rested her head on the steering wheel, fighting back an impulse to vomit. The contrast was an obscenity. Huge magnolias here lined the street on both sides, giving deep dappled shade to the well-paved highway. Between the road and the white concrete sidewalks rose great greening mounds of juniper and ivy, and beyond them, with manicured lawns and discreet sprinkler systems, were the complacent mansions of the rich.

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

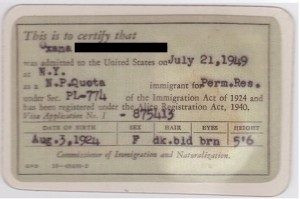

The citizenship decision

In 1972, five years after I emigrated to the US clutching my hard-won Green Card, my official status was Resident Alien. I was required to register at the Post Office every January. If I wanted to leave the country, I had to prove that my income tax payments were up to date. I had to remain “of good moral character” and could be expelled if I had a run-in with the law. And I couldn’t vote.

Meanwhile, opposition to US involvement in Viet Nam was heating up. A turning point for me was the May 1970 killing and wounding of students by members of the National Guard at Kent State University, where students were protesting the secret bombing of Cambodia. As a history major, I already understood why interference in another country’s self-determination was bound to end badly. It was obvious to me as an outsider that the Viet Nam War was a disaster. Yet here in this supposed Land of the Free, it seemed that the authorities were beating up people who said so.

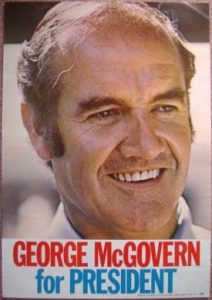

If I couldn’t publicly protest, and I couldn’t vote, at least I could help behind the scenes. I became interested in the anti-war policies of presidential candidate George McGovern, and began to volunteer in his California primary campaign. Here’s how I described my activities in a letter to parents:

June 2, 1972

I have been sticking my neck out in other directions lately too – have become very involved in George McGovern’s presidential campaign. I have put in some time at the campaign headquarters, and then got nailed to organise the local precinct. It is really rather fun, once I got over the initial panic. Support for him is very strong in this area, so I was lucky in the number of people I could con into working for me. Our house is going to be the headquarters for all 30 Cupertino precincts Tuesday (election day), so that should be interesting too. Am meeting all sorts of interesting people, especially the out-of-state students who are travelling around working for him. There are some neat kids amongst them.

McGovern won the nomination, but lost the November election to incumbent Richard Nixon. Meanwhile, I was feeling ambivalent about my own status. After five years in the US, a Resident Alien may commence the application process to become a citizen. Was I ready to do that? Could I turn my back on the land that had nurtured me and my ancestors? Could I pledge allegiance to a country whose foreign incursions I could not support? On the other hand, how badly did I want to share with my neighbors in making decisions about this place we all now called home? For most immigrants, this is a decision that requires careful thought and soul-searching. In the end, my husband and I decided to apply for citizenship. We didn’t know then how many years, frustrations and phone-calls it would take. But that’s another story.

Political women in the 1970s

In early 1972 I had a note from the women’s editor of my New Zealand newspaper requesting pieces on how the women’s liberation movement had changed the role of women in politics. “Surely,” she said, “women over there do more than make tea for the candidates.” My response was a two-part series. First, the attitudes and roles of party workers in my county, now more widely known at Silicon Valley. In my next post, I’ll share a profile of a woman political candidate.

Women in Politics Part I:

Party workers reflect range of attitudes

Santa Clara County, CA, 1972

The grey-haired woman in the Republican campaign trailer sniffed contemptuously. “Women’s lib! I don’t hold with all that stuff.” She is the wife of a retired army officer, and a veteran of political campaigns. Meanwhile, the Republican incumbent for her Assembly district is being challenged by a feminist woman Democrat, and in Southern California the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party is seeking to abolish itself, on the grounds that a separate women’s organization is sexist in conception.

These are the extremes in the spectrum of views on women’s place in the world that the political party workers of Santa Clara County, CA reflect in their organization, their activities, and their attitudes.

Organization at the state level is set for both parties by the state code. Each legislator or party candidate has up to five nominees to the State Central Committee of his party, of whom at least two must be women. From this 1,000-strong body, a man and a woman for each Congressional District are chosen to form the decision-making executive committee.

“The women have a great deal of influence,” says Loretta Riddle, field representative and campaign coordinator for State Senator A. Alquist, who has served on the executive committee for ten years. “It has been a very fair thing. If you have the ability, and work hard, you can make your voice heard.”

The presence of a few women is customary, though not mandatory, on the elected County Central Committees. But at this level the loose structure imposed by the state gives way to local idiosyncrasies. The Democratic Party, though overwhelmingly the majority part of the county, admits to being fragmented and disorganized. The Republicans, on the other hand, pride themselves on their efficiently centralized hierarchy. Robert Walker, executive director of the Republican county headquarters, has the county committee divided into specialized sub-committees, and keeps close liaison with his party’s many volunteer clubs.

In contrast to the 600 members that the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party can muster, the thirteen chapters of Republican Women’s Club in the county have a total of 3,000 members. Ten of the clubs run their own local campaign headquarters, registering voters and handing out literature for all the Republican candidates. They are also the labor force of the campaign. “Those women are fantastic,” says Mr. Walker. “I can send them a 30,000-piece mailing and get it back the next day all ready to go.”

The Democratic women have a project too: they run the county headquarters for the party. Madge Overhouse, its director, feels that she has a strong voice in the running of the party organization. “But it is simply by going ahead and doing something like this. Within the Democratic Party you can come up with an idea and follow it through.”

“Individual effort” is an idea often expressed by Democratic women; “femininity” comes more often to the lips of Republicans. The northern chapter of the Democratic Women’s Division, though less militantly feminist than its counterpart in Southern California, puts most of its fund-raising effort into the campaigns of women candidates. Ladies’ club activities like luncheons or fashion shows, favorites of the Republican women, are not popular with Democrats. “We are more issue-oriented,” says Madge Overhouse.

The advantage of clubs, thinks Robert Walker, is that they attract people who would not ordinarily be involved with the party. He described the Republican Party as “the party of the middle class. They tend to be socially oriented, and this carries over to their approach to doing political work. They want to gain some prestige out of it.”

Joan Menagh was a founder of the Republican Women’s Club in her neighborhood. While enjoying the social aspects, she stresses that education is its primary purpose. “Volunteerism” has been a popular topic for speakers. Traditional social values prevail. Though she has worked up to a seat on the County Central Committee, and a full-time job in the office of U.S. Congressman Ch. Gubser, Mrs Menagh claims to have no political ambitions. “In my life my husband and family come before any of my other activities.”

Democrat Madge Overhouse is also critical of the more militant factions of her party. “We have to recognize that there are a good many women who are perfectly happy to be wives and mothers. The militants are cutting these women off, and I think it’s too bad.”

Nor for that matter will Loretta Riddle run for office, partly because she wants to stay close to her two teenagers, but mainly because her personality is satisfied with the considerable power she already wields behind the scenes. She does however admire women who have aspirations to high office, and is longing to see a woman in the California Senate. “I don’t think men realize how much they need women in politics. Women have a certain sensitivity and perspective that men do not.”

Both Republicans and Democrats see a trend toward more women in public office. “I think it goes back to this whole women’s lib thing,” says Republican Joan Menagh. “Women for many years didn’t feel that running for public office was a particularly feminine thing to do, and voters in the past didn’t feel that a woman could hold her own within the political arena as a candidate. Both ideas are passing.”

Democrat Loretta Riddle agrees. “People have not yet learned to accept women who are forceful. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t go ahead, because then we may go along and start learning little by little.”

The way is open for a woman to rise as high in politics as her ability, tenacity and sheer personal drive will allow. It is a difficult path though, and few are willing to take it. The vast majority of women in political campaigns will no doubt continue to stuff envelopes, sit at voter registration booths, check precinct lists, and make tea for the parched throats of campaign speakers.

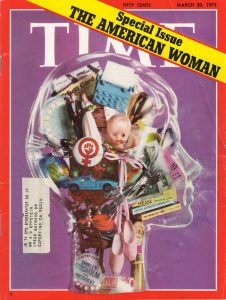

Time Magazine on women, 1972

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

The issue starts, as usual, with letters to the editor. These are from female readers responding to the magazine’s invitation to “write to us about their experiences and attitudes as women, and to tell us how their views on this subject have changed in recent years.” I tabulate the responses. Twenty enthusiastic about the new feminism, three ambivalent, and six tending negative, arguing that, since very few higher level jobs are available to women, by going out to work they “trade the drudgery of housewifery for the drudgery of an office job.” Or, as another writer put it: “Rush out each day to that exhilarating, high-paid position; rush home to that hot-cooked supper (cooked by whom?); relax in that nice clean living room (cleaned by whom?). Most likely, dearie, you’ll hold down two jobs—‘cause when you get home from that executive job in the sky, there ain’t gonna be no unliberated woman left (and certainly no man) to do your grub work.” Sidebars titled “Situation Report” in the various sections of the issue reflect these caveats: prejudice is rampant against allowing women into higher paid or managerial professions.

Time’s editorial attempts to define “the New Feminism” as “… a state of mind that has raised serious questions about the way people live—about their families, homes, child rearing, jobs, governments and the nature of the sexes themselves. Or so it seems now. Some of those who have weathered the torrential fads of the last decade wonder if the New Woman’s movement may not be merely another sociological entertainment that will subside presently.”

Subsequent pages offer a history of the currents of social change that “have converged the make the New Feminism an idea whose time has come.” There are portraits of a range of American women, a piece on “the organizations, aims, difficulties and range of opinions that help make up Women’s Liberation in all its diverse forms,” a one-page snapshot of attitudes in Red Oak, a small Iowa town. Here’s a quote: “Many Red Oak women agree with Doctor’s Wife Jane Smith: ‘A woman’s place is in the home taking care of her children. If a woman gets bored with the housework, there are plenty of organizations she can join.’” A photograph shows Mrs. Smith entertaining friends at bridge. I have a flash of memory: one of my sisters saying the same words to me.

The “Politics” section of the magazine showcases some familiar names: Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Martha Mitchell, and describes the bipartisan effort of the National Women’s Political Caucus to get more women elected, or selected, as delegates to the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

The “Science” section describes the difficulties a woman astronomer faced. As a woman Margaret Burbidge, who helped develop a new explanation of how elements are formed in the stars, “found that she could get precious observing time at Mount Wilson Observatory only if her husband [a physicist] applied for it and she pretended to act as his assistant.” The Burbidges also ran into nepotism rules at the University of Chicago. “’The irony of such rules,’ says Mrs. Burbidge, who had to settled for an unsalaried appointment while her husband was named a fully paid associate professor, ‘is that they are always used against the wife.’” I think of women scientists I have known who suffered the same exclusion, such as Beatrice Tinsley, a British-born New Zealand astronomer and cosmologist whose research made fundamental contributions to the astronomical understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow and die. Beatrice had to divorce her husband, a Texas University professor, and move to Yale to gain the position she needed to do her work.

In many science fields, recognition for outstanding women is still abysmally low. I think of efforts by my son David, a mathematician, to redress the paucity of profiles of eminent women mathematicians in Wikipedia.

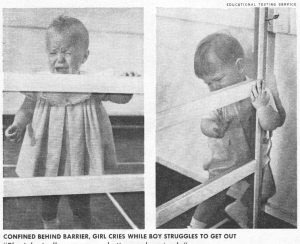

Section after section, the stories continue. “The Press” section is subtitled “Fight from Fluff,” how women’s pages are shifting to more general interest features. ”Modern Living” talks about efforts to find new pronouns, the opening of day care centers, and changes in marriage dynamics. The Situation Report for the “Law” section puts the number of women lawyers in the U.S. at 9000, 2.8% of the total number of lawyers. Of this small number, “less than 12% of them were making more than $20,000, as compared to 50% of the men.” Similarly depressing are statistics for recognition of women in the arts, in business, and in medicine. The “Behavior” section, which looks at research into sex-related differences in early childhood, seems to reinforce stereotypes: “Many researchers have found greater dependence and docility in very young girls, greater autonomy and activity in boys.” The accompanying pictures show two babies behind a barrier set up to separate them from their mothers. The little girl cries helplessly; the boy struggles to get out.

A keynote essay by Sue Kaufman, author of the novel Diary of a Mad Housewife, attempts to capture the feelings of a composite American woman, interested in the new ideas, admiring of feminist leaders, but cautious about jumping on the bandwagon. Kaufman describes an imagined scene: an admired leader is coming to town to speak. The woman arranges for a babysitter. “She will go, usually with friends. They will arrive … take their seats—and slowly it will begin to happen … she begins to feel the flickers and currents of a mass communion, a rising sense of excitement that she imagines parallels what one feels at a revival meeting … this powerful thing happening, this sweeping, surging, gathering-up-momentum feeling of intense camaraderie, solidarity movement.” After the meeting is over, Kaufman describes the woman driving home, paying the sitter, returning to the children and the kitchen “to take up the reins of her existence. Only—something is wrong. She is overwhelmed by a terrible sense of wrongness, of jarring inconsistency. There was that surging, powerful feeling in the hall, and now, stranded on the linoleum under the battery of fluorescent kitchen lights, there is this terrible sense of isolation, of walls closing in, of being trapped. …but she doesn’t burst into tears. …In spite of the desolation she feels, she knows that she is not alone…there is enormous comfort in knowing that. And knowing that is one of the big changes in her life.”

Recycling centers: the old days

Rummaging through my old black filing cabinet, I came across an article I wrote in 1972 about recycling centers that was published in my Christchurch, New Zealand paper. These days, when everything recyclable gets dumped into the Blue Bin and carted away, I though it might be fun to read about the beginnings of the movement.

Rummaging through my old black filing cabinet, I came across an article I wrote in 1972 about recycling centers that was published in my Christchurch, New Zealand paper. These days, when everything recyclable gets dumped into the Blue Bin and carted away, I though it might be fun to read about the beginnings of the movement.

COME ON DOWN TO THE RECYCLING CENTER

Cupertino, CA

Spurred on by their ecology-minded kids, Californian families these days are loading up the station wagon at weekends with squashed cans, bottles, aluminum foil, and old newspapers, and heading for the local recycling depot.

The movement started a few years ago, when beer manufacturers discovered that they could earn bonus points in public relations by buying back and recycling the aluminum beer cans that had become an inevitable part of the landscape of the nation’s beaches and parks. As concern for the environment became a national obsession, clean-up campaigns became a fashionable, and profitable, project for youth groups.

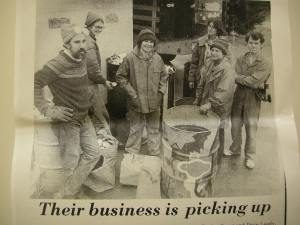

A 1970s recycling center. Image from Bainbridge Island, WA Community Cafe

Then the kids started taking over the collection depots. Each summer, high school social studies departments set up their own recycling centers. Sometimes the logistics of getting students organized can be overwhelming. One summer the boxes and bottles piled up embarrassingly high in the parking lot of a local supermarket before the kids from the high school across the road got themselves coordinated. And last year student apathy on the prestigious Stanford University campus allowed the recyclable trash to spread like a slum over the elegant grounds.

But a well-run recycling center can be a pleasure to visit. A Los Altos youth group set up shop in the grounds of an abandoned school. Every weekend enthusiastic volunteers were there, sorting, packing, stacking. Cheerful hand-lettered signs directed customers to the right cardboard carton for each item, and warned about the broken glass on the ground. One member invented an ingenious wooden lever for pressing the cans as flat as can be, and this is always in use, though most families now bring the stuff in already sorted and squashed. “Doing your bit for ecology’ has become an acceptable chore for children, and there is a therapeutic value in bashing cans nearly comparable to chopping firewood, back in the good old days before central heating and all-electric kitchens.

Some local government projects have fared less well. Neighboring Sunnyvale’s municipal recycling center is a lonely outpost in the corner of the city dump, way down in the swamp beyond the aerospace plants and the defense installations. Not surprisingly, the center made a loss last year.

Cupertino has tried to get the best of both worlds. The local chapter of Jaycees, supported by the city, the college administration, and the students’ Ecology Corps, has set up a recycling depot in a corner of the beautiful, and central, De Anza College grounds. It is less chaotic than the Los Altos center: a neat redwood fence surrounds the area, and the materials are contained in big steel skips. But there is still the sense of community involvement, the cheerful bustle on a Saturday morning, the satisfying clunk of bottles smashing into the skips. First quarter earnings showed a modest profit. The glass and aluminum are bought back by their respective manufacturers, and the tin and bi-metal go to a local producer of nursery pots.

Some recycling centers take newspaper, which is now reused for a variety of items, from dinner napkins to stationery. But the youth club paper drive, long a part of American life, takes care of most of this, and the big brown newspaper skip on the local school grounds is a familiar part of the landscape.

What about the future? Development suggestions have included a return to the regular garbage collection, with automatic sorters at the dumps to pick up reusable materials. The idea sounds more efficient, more appropriate to industrial America. But somehow it doesn’t quite fit the new environmental consciousness, with its emphasis on individual effort. And it won’t be nearly so much fun.

A discovery in the sky

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken

—John Keats

A letter to my parents:

31 March 1970

…This morning we had another memorable experience: Tony got us up at 4:30 am to see Bennett’s comet, which is visible in the east at this time. This is believed to be a new comet, and is an extraordinarily beautiful sight, with its huge tail trailing. Can you see it from New Zealand?

The Southern Cross and its Pointers. Image from Te Ara–Encyclyopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz

Since I was a child, learning from my father how to find due south from the Southern Cross and its Pointers, I have been fascinated by the night sky. In my homeland of New Zealand I could point out some of the interesting phenomena: the Coalsack nebula, the Magellanic Clouds. An immigrant to the Northern Hemisphere I was still learning the northern sky.

In 1970 I was too busy with children and their needs to study more about the new comet. I’ve now learned that it is considered one of the greatest comets of the past century. It was discovered on Dec 28 ,1969 by an amateur astronomer, Jack Bennett, in Pretoria, South Africa. It seems we have a southern constellation in common. From his obituary I learned that Bennett, who died in 1990, “became interested in Astronomy when as a teenager, his mother used to point out to him the Southern Cross and the brightest stars and planets, in the evenings after church service, on their way back home.”

Daniel Verschatse took this 1970 photograph of Comet Bennett near the town of Waasmunster in Flanders (Belgium).

The astrophotographer Daniel Verschatse notes on his website:

“For two decades, starting in the late 1960’s, the southern sky was patrolled by a dedicated South African comet-hunter named Jack Bennett. Using a 5-inch low-power refractor from his backyard he discovered two comets. Jack also picked up a 9th magnitude supernova in NGC 5236 (M83), becoming the first person ever to visually discover a supernova since the invention of the telescope.”

I also learned that Comet Bennett is estimated to have a period of 1700 years. So if it previously appeared in Earth’s sky, it would have been in the third century, about the time that the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great was a baby. Britain was still under Roman rule. In my ancestral Ireland, Cormac mac Airt reigned as High King from his seat at Tara.

The Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) atop the Hill of Tara, County Meath, where the High Kings of Ireland were traditionally installed.

Comet Bennett’s next perihelion, or point at which it is closest to our sun, is predicted to be the year 3600. Might it still exist by then, and might there be humans left to see it? Who knows?

A tale of a sparrow

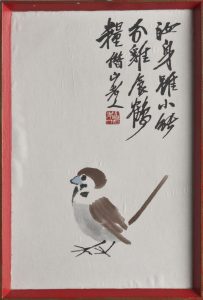

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

14 April 1969

A friend of Tony’s from Memorex came to dinner. A Korean boy … He is really charming, and we had a pleasant evening. One interesting thing that came out of it – Yun also reads and writes Mandarin Chinese, so was able to translate the inscription on our sparrow picture for us. Do you remember our sparrow? It is a little brush drawing that Tony picked up in a junk shop in Hawera when he was a student, shortly before reading in a magazine a story about a famous Chinese artist who was objecting to a government campaign to kill off the sparrows to improve the wheat production. He made these little posters, inscribed with sentimental stories about the sparrow. And this, as far as we can tell, is what we have got.

With the help of the Internet, I’ve been piecing together my fragments of knowledge about this period in Chinese history. What I discovered is a familiar story about well-intentioned interference with nature leading to ecological disaster.

In the First Five-Year Plan of the newly-founded People’s Republic of China, families were each given their own plot of land. In the Second Five Year Plan, begun in 1958, a new agriculture system was announced. Family farms were grouped into collective farms, making each village a single production entity in which everyone would have an equal share. Food would be provided in a communal kitchen.

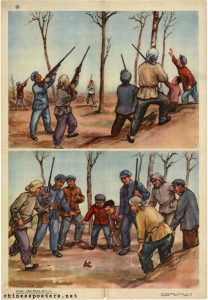

In theory, a collective farm where resources were centrally controlled should be more efficient and yield higher productivity. In practice, agricultural production figures fell. Food shortages were exacerbated by flood and drought. Believing that getting rid of sparrows, who ate grain, would improve production, Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Four Pests Campaign, which encouraged citizens to kill them, along with three other pests: rats, flies, and mosquitoes. Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks were killed. Many sparrows died from exhaustion; citizens would bang pots and pans so that sparrows would not have the chance to rest on tree branches and would fall dead from the sky. Citizens also shot the birds down from the sky. These mass attacks pushed the sparrow population to near extinction.

In hindsight, the result was inevitable. Too late, Chinese leaders realized that sparrows didn’t only eat grain seeds. They also ate insects. With no birds to control them, insect populations boomed. Locusts, in particular, swarmed over the country, eating everything they could find, including crops intended for human food. People, on the other hand, quickly ran out of things to eat, and tens of millions starved.