Archive for the ‘travel’ Category

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

Night train in winter

New Zealand’s Volcanic Plateau in daytime. Image from https://www.flyingandtravel.com/skiing-north-island-whakapapa-ruapehu/

An image haunts my mind like an old song in a minor key. From a train window late at night, a desert plateau spreads into the distance. In the foreground, scattered clumps of tussock, stiff with frost, emerge from a dusting of snow. On the horizon, three volcanic cones gleam white against the blackness. The scene is both bleak and beautiful. Tranquil even. A calmness fills me as I remember.

The year was 1968, the place the center of North Island, New Zealand, somewhere north of Ohakune on the Main Trunk Line. I was traveling by train, alone, to a funeral.

It had been a tense few months since my husband and I, with two young children, had decided to make the trip back to New Zealand, our home country, to visit our families. First there was boundary-setting to do with my mother on how much relation-visiting I would allow her to inflict on my shy infants. A few weeks prior to our departure date the children developed chickenpox, one after the other, pushing our schedule further into New Zealand’s winter and upending an itinerary that carefully divided our limited time between my husband’s family and mine. On arrival, I discovered my mother had sabotaged this division by taking a motel room in my mother-in-law’s town. Each day she ensconced herself in mother-in-law’s tiny living-room, dragging my embarrassed father and school-age sister with her. Other sisters later told me they’d remonstrated with her, but she’d insisted she had a right to see her long-gone daughter as soon as I arrived. My mother-in-law was gracious, but I was furious on her behalf.

Then fate intervened. On a night of heavy rain, my maternal grandmother’s husband stepped from between parked cars into the path of an oncoming truck. I did not know my step-grandfather, since he and grandma married about the time I left for college. But grandma had been an important part of my childhood, and she loved this man, so it mattered that I go to the funeral. Leaving the children with their father and his mother, I set out on the overnight journey. First a railcar from New Plymouth, on the west coast, which connected at Marton with the Night Limited express that ran each night between Auckland and Wellington.

I knew this train, having ridden it back and forth many times when I was in college. There was comfort in the familiar sway and smell of the overheated, stuffy carriage, the faded red plush covering high-backed seats, the clackety-clack of the wheels. There was peace too. For the first time since the children were born I was alone, with no responsibilities.

Beyond the desert and mountain vista on the Volcanic Plateau, the chuff and grind of the diesel engine became more labored as the narrow-gauge track rose into a more broken landscape, with forest a dark overhang outside the window. Then Taumarunui Station at 2:00 am, the refreshment stop, where bleary passengers streamed into the tea-room for meat pies or slabs of yellow pound cake and milky tea in thick white china cups. Sometime around dawn, a stop at Te Kuiti where relatives met me for the two-hour drive to Tauranga, where the funeral was to be held. Calmed by the journey, I willingly renewed acquaintance with uncles and cousins and aunts I’d argued with my mother about seeing.

Looking back, I understand what that spare, snow-covered landscape was telling me: that the land is vastly more important than human quarrels, that I needed to let go of my day-to-day tensions and anxieties and become merged with the wholeness of the earth.

Wide-eyed with wonder at the sights

Who can forget their first view of the Golden Gate Bridge? Or their first visit to California’s wine country. A breathlessly enthusiastic October 1967 letter to my New Zealand parents about a one-day excursion offers this immigrant’s impressions.

…We finally got away about ten, and headed north on the Nimitz Freeway, which runs up the east side of San Francisco Bay, past Oakland and Berkeley. Our destination was the Napa Valley, which is at the northern end of the bay. This is one of the most important wine growing districts of California, specialising mainly in dry wines similar to those of the Rhine Valley in Germany. A lovely day, and the air in the valley so crisp and clear – a pleasant change after the usual hazy smog of this valley. We went up through Napa itself – interesting little market town, with houses very reminiscent of New Zealand colonial architecture. We got a bit lost getting through the town, which made it more interesting – back streets are always more interesting than the usual bypass highway.

Our first stop was at Yountville – just a tiny hamlet with a huge old winery building, now disused, and converted into an art centre – fascinating little booths selling antiques, objets d’art, etc. One of the latest crazes here is digging up old bottles and other trash from the old mining towns – some of these fetching fantastic sums in such markets! We sat on the terrace of a little café nearby and had coffee and watched the vineyards and the hills. The café used to be the old Wells Fargo stage stop, now converted. We then took a side road across to the other road that runs up the valley, the Silverado Trail – very quiet and empty, and beautiful scenery. The valley is long and narrow, with mountains on either side, and vineyards covering the flat valley floor. We stopped off by a dry river bed to have our lunch, then went on to visit a winery. We chose Beaulieu, a fairly small one, where the emphasis is on quality rather than mass-production. It was rather nice, too, in that it was not at all touristised, unlike another that we stopped at later – a German one, with a replica of the family home on the Rhine – a fantastic German high Gothic mansion, entirely over-run with tourists and touristy gimmicks. By contrast, the reception and tasting room at Beaulieu was a simple stone building under plane trees, very simply and sparsely furnished with red brick floor and wooden benches. We were taken on a tour of the winery – wonderful aromatic smell of the freshly picked grapes going through the crushers, and the coolness, and row upon row of vast redwood settling tanks, some of them holding up to 20,000 gallons.

We took an interesting route home – partly because David [our four-year-old] has been breaking his neck to go over the Golden Gate Bridge. We climbed up the mountains on the west side of Napa – magnificent panoramic view of the valley floor – then dropped down the other side into Sonoma Valley at Glen Ellen, another tiny sleep hamlet, with even some original log cabin buildings. Near Glen Ellen is Jack London’s ranch, now a state park. None of us knew much about Jack London, but found it a delightful place to have a picnic tea, then walked up a little path through the trees to a revelation of a house. It was built by his widow of big fieldstones found in the grounds, as a memorial to him, and now used as a museum. From the odds scraps of manuscripts that were there I was quite impressed by his style. Probably you know more about him than we do. He died in 1916, wrote during the early 1900’s, “The Call of the Wild,” and “The Cruise of the Snark” among others. But that house was just wonderful, especially the exterior – I have never seen a place that so perfectly fitted into its surroundings.

The sun was going down as we drifted down the Sonoma – the Indian name means ‘valley of the moon’ – making the layers of hills distinct in different tones of gold. Over a few more hills into Marin County, past the gay houseboats in the artists’ colony of Sausalito, then suddenly, there was the most extraordinary view, just over the crest of a hill. Just below us the huge red towers of the Golden Gate Bridge, and across the water the skyline of downtown San Francisco, all pink and pastel in the setting sun. The huge golden sun was dropping slowly into the waters of the Pacific as we drove across the bridge, and by the time we had got through S.F. it was dark, with car headlights making thick ribbons of light on the freeway interchanges.

The last time I saw Paris

An old letter from my black file cabinet brought back memories of a brief vacation in Paris in 1962. Rereading the headlong, crammed-onto-the-page text, I hear again the breathless voice of a wide-eyed young traveler falling in love with the city of light.

I’ve not been back to Paris. It’s likely I never will. But, as in the old Jerome Kern song, I’m happy to remember her as I saw her back then.

Listen to Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

singing “The Last Time I Saw Paris.”

Windsor, 24 Sept

Dear Mum & Dad,

Breakfast tray at our door each morning: croissants with butter and jam, café au lait–the height of luxury.

Back home in England again, and not particularly pleased to be back to these bleak autumnal mists, and a real stinker of a cold to go with it—first cold I have had for ages. We had a wonderful week in Paris, and fell in love with the city. Left very early Monday morning—rose before the sun, about 5 am, and took off at 8 in a Caravelle, a very fast French jet plane, which landed us in Paris before 9 – though it was after 10 by the time we got to our hotel, which was in a little side street off one of the main boulevards. Rather noisy, at least for the first night, as it was close to the great city market, which does its business in the small hours of the morning. The second night we didn’t even notice it. Nice room, with a balcony from which we could watch all the goings-on in the street below—most entertaining. We spent practically every day walking—the number of miles must be pretty high. First morning we went down to the old centre of the city, the Île de la Cité, an island in the Seine, and had a look at Notre-Dame—I hope you got the postcard I sent you of it. Spent the rest of the day pottering round the island, along the banks of the river to the Tuileries, and back by a more or less circular route to the hotel. The next day we went up to the north side of the city, to the hills of Montmartre—fascinating streets, most of them ending in steps, somewhat like parts of Wellington, and with graceful balconied buildings with the plaster peeling off. About midday we went out to the woods of Boulogne, a huge park just out of the city, where we watched workmen playing at bowls in their lunch-hour. It is a sort of grown-up marbles, played with heavy steel balls that you throw to knock out the kitty. Then we went back to the Arc de Triomphe and walked down the Champs Elysees—lots of interesting shops, and the wide street incredibly tightly packed with vehicles—you look down the street and you see nothing but a sea of car roofs. Traffic in Paris is very thick, very, very fast (no speed limits) but amazingly well organized. Pedestrians beware though—they are very much second class citizens, and boy do they hop when the traffic starts to move. Anyway, back to Tuesday—later in the afternoon we went over and had a look at the Eiffel Tower—a remarkable piece of engineering. We didn’t go up it, however—we had already seen enough views of Paris from above, and weren’t very keen on its reputation for swaying.

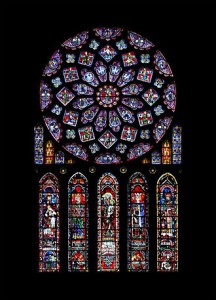

The next day we met my college friend John Wilson, who is at present living in Paris, and he took us out for the day in his little car, one of the new utility model Citroens. You may not have seen them in New Zealand. A chopped-off little bug, a bit ugly, very mass-produced, but able to go anywhere, very cheap, and very comfortable to ride in. There are thousands of them in Paris. Went first to Versailles, to look at the palace where the king and Marie Antoinette were taken from to have their heads chopped off. A most impressive building (though we didn’t have time to go inside), and the gardens are incredibly beautiful, in a cool, formal sort of way. Mostly vistas of fountains and pools, with statues, with a few formal flower beds, and woods beyond, laid out with a grace and elegance unknown to these more democratic times. We could have stayed there just wandering all day, but had to get going again, through side roads and quaint little villages. We had lunch in one, at a street café in the village square, just outside the gates of a very charming old chateau, whose towers were reflected in the canal close by. Then on to Chartres. The cathedral stands on a hill overlooking the plain, where there has been a church since the third century. This one was built in the 13th century, and was remarkable in that, except for part of one tower, which is noticeably odd, it was completed in thirty years. Outside very elaborate and impressive relief carvings in the porches, lots of gargoyles and what not.

You go inside, and it seems at first quite dark. Then gradually, as your eyes get used to the light, the huge pillars begin to appear, lit up by a pale greenish, strangely luminescent glow. Then you look up, and are practically dazzled in the burst of red and blue and green. The stained glass windows of Chartres are said to be the most magnificent in the world, and I can well believe it. To the north, south and west are huge rose windows, and all around are arches, each closely worked with many little pictures of saints, in incredibly fine detail. The result is a blaze of pattern and colour.

Then back the sixty miles to Paris, through wide open fields—no fences in this region, and the land is fairly bare of trees, and with a very gentle swell. It is a grain growing area—lots of harvesting machinery, and everything a beautiful golden colour—even the soil is the same colour as the wheat stubble. The next day we went to the Louvre museum, or at least to a small annexe, the Impressionists gallery—Van Gogh, Renoir and co., and discovered again the beauty of many of the paintings that we had thought a bit hackneyed in reproduction—things like Degas’s ballet pictures for instance—very beautiful and subtle in the originals. Spent all morning there, and in the afternoon walked over to the other side of the city, to see the UNESCO building, a very fine modern building. Our favourite part of it was a Japanese garden in the grounds, a little area of different levels and contrasting textures of stones and gravels, a stream and a pond, and a few bushes. Sounds rather stark and uninteresting to describe, but the result was charming, and very peaceful and relaxing. Friday back to the Louvre, to the main museum this time, but when you think that each of the wings of this is about a mile long, with several intersecting galleries about half a mile across, and all several stories high, you will realise that we didn’t see much of it, and even what we did see—mostly Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, there were so many fascinating and beautiful things to look at that we didn’t do them justice—excuse for going back! Later in the afternoon we had to think of getting ourselves back to the airport. Bought some beautiful (smelly) French cheeses from one of the many street markets, then got out to the airport to catch our plane at seven. Wonderful to see the lights of London as we flew over the city—when we got under the cloud, that is. Very exhausted by the time we got home, but still wouldn’t mind doing it again. Though went into London yesterday, to see [our friend] Bill, an exhibition at the Tate, and a concert at the Festival Hall, and decided that London was rather lovely too.

Vive la France! Love, Maureen

Droplets in an immigrant wave

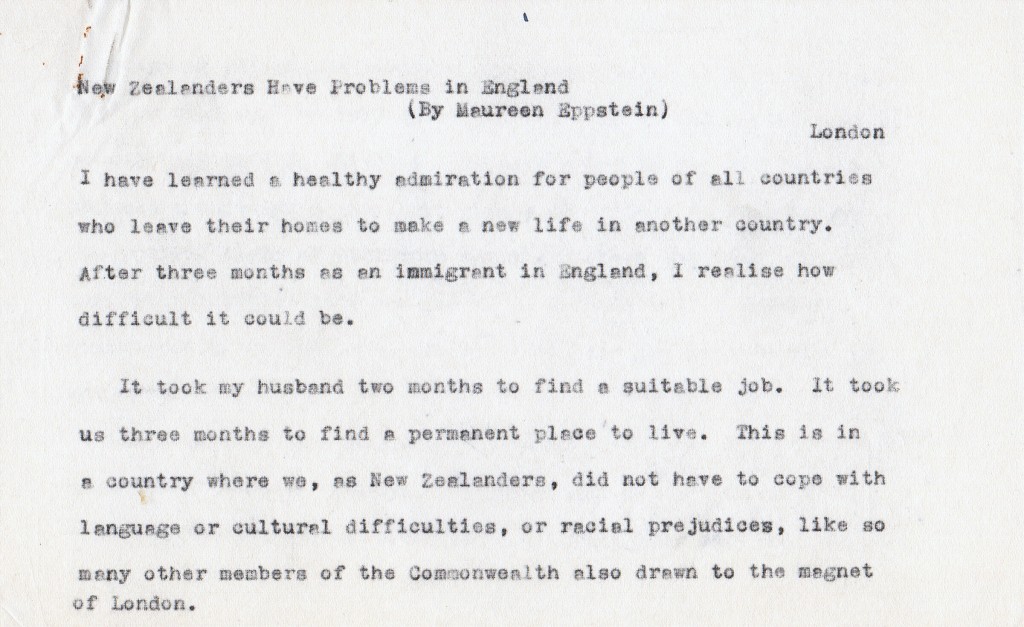

In a 1962 article I wrote for my old paper, the Christchurch (NZ) Press, a draft of which I found in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

I have learned a healthy admiration for people of all countries who leave their homes to make a new life in another country. After three months as an immigrant in England, I realize how difficult it could be.

It took my husband two months to find a suitable job. It took us three months to find a permanent place to live. This is in a country where we, as New Zealanders, did not have to cope with language or cultural difficulties, or racial prejudice, like so many other members of the Commonwealth also drawn to the magnet of London.

We had no idea at the time of the hugeness of the immigration wave in which we floundered. To aid in post-war reconstruction in the 1950s, Britain had recruited labor from its colonies, primarily the West Indies and the Indian sub-continent. At that time people from the Empire and Commonwealth had unhindered rights to enter Britain. However, by the late 1950s, with the British economy faltering, racial prejudice reared its violent head. The Conservative Party government proposed legislation to make immigration for non-white people harder. One aspect of the proposed bill was to deny entry to dependents of immigrant workers. Before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 could go into effect, the entry of dependents into Britain increased almost threefold as families attempted to beat the deadline. Total immigration from what was known as the New Commonwealth swelled from 21,550 in 1959 to 58,300 in 1960 and a record 125,000 in 1961.

Statistics are from Paul Foot, Immigration and Race in British Politics (Penguin, 1965)

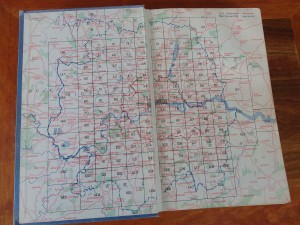

All these people needed somewhere to live. It is no wonder then that rents soared and accommodations of any sort were snapped up. While Tony job-hunted, I haunted rental agencies for a short-term apartment (or flat, as they’re called in England) and, the hefty Bartholomews Atlas of Greater London under my arm, braved the Underground and navigated the suburbs. My letters to parents are full of observations like this one:

It’s amazing how so many of the little villages that have been absorbed into the city still retain their village atmosphere – you pop up from an Underground station and could imagine yourself miles out in the country – unless you happen to be on a bit of a rise, when you see nothing but houses as far as the eye can see. One place I visited, for instance, Muswell Hill, you had to go by bus through a very extensive patch of woodland to get to it. That place I didn’t take, incidentally, because the bath was in the kitchen – covered by a lift-up board and a little frilly curtain. When I mentioned this to another English landlady she didn’t even raise an eyebrow.

My letter continues:

We have now moved out of our hotel into a bedsitter out at Hampstead, for which we are being grossly overcharged – I guess we just took it in a moment of desperation.

The rent was six and a half guineas a week (the same buying power as about $200 in current U.S. dollars.) Every piece of furniture was shaky about the legs, and the cooking facilities were two gas rings crammed into a cupboard with about six inches of counter surface. The shared bathroom was down the shabby hall. I described the landlady as

a bit of a social type – she was too busy preparing for her cocktail party last night to attend to our wants, which brassed me off considerably. Still we get on quite well with her little dog, so with a little careful handling relations might improve.

Relations did not improve. Still vivid in my mind is one of our shouting matches. I had returned from the local laundrette with clothes still damp, in spite of multiple coin feeds to the drier, and had strung clothesline around the room. In walked Mrs. Ashley-Davis. “My furniture! My furniture!” she wailed, hand to her heart. Other disputes must have followed. In a letter to parents dated May 25, after giving the news that Tony had accepted a job near Windsor, I mention that we have given notice

…after some somewhat violent disputes with the landlady, in which I managed to lose my temper – catastrophe!

Finding permanent housing proved even more frustrating. I told my parents:

…for the last three or four days we have been footslogging, railriding, bussing, and generally getting fed up in a wide arc around the area…

We moved out to a hotel near Tony’s new job. My letters for the next few weeks are full of the false hopes and discouragements of the search. Finally we got lucky: a second floor flat in a Victorian brick semi-detached house just down the hill from Windsor Castle. A roof over our heads at last!

Here’s a modern Google Maps street view of the neighborhood. It still looks much the same.

Red is the color of lost empire

In the 1940s, when I was a schoolchild in New Zealand, we used our red pencils to color in maps of the world. Great Britain, of course: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (Eire was gone by then). Huge chunks of the African continent that still had their old names and boundaries: Sudan, Gold Coast, Cameroons, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, South Africa are just some I remember. The Indian subcontinent with neighboring Ceylon and Burma. Pieces of the East Indies archipelago. Australia, our nearest neighbor. Little red dots, lots of them, for Pacific island dependencies. The big swathe of Canada. More dots in the Caribbean, and a dab for British Guiana on the South American mainland. We pressed our red pencils hardest for New Zealand, the furthest outpost of the British Empire, on which, it was said, the sun never set.

This website has a fascinating time lapse view of

the rise and fall of the British Empire.

Even as we children beamed with pride at our splendid red maps, our world was changing. By the time I moved to England in 1962, the political geography I knew as a child was obsolete. The British had retreated from the Indian Empire, leaving behind a land painfully divided between Hindu and Moslem. The red chunks of Africa rearranged themselves into separate nations. South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand declared themselves a Commonwealth, still recognizing the Queen, but independent of British rule.

Old loyalties die hard. The Union Jack still fills the top left corner of the New Zealand flag. In 1962, New Zealanders still looked to England as the “mother country” and I could write to my parents, in my first letter from London: “[W]e have finally arrived in the Heart of the Empire.”

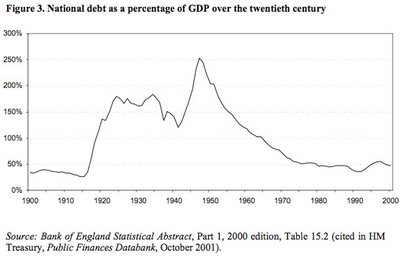

The mood I encountered in the old empire’s capital was bleak. Great Britain had survived World War II, but at an enormous financial cost, and the national debt hung like a shadow over the economy.

After the austerity of the 1950s, living standards were improving, but the country’s wealth, prestige and authority had been severely reduced. Economically, Britain was slipping behind its competitors. Relations between management and labor were bad; the newspapers were full of reports of strikes and unrest. It did not feel like a good place to be starting a new adventure.

Discovering the familiar

When I first went to London, I already knew it, or thought I did. The literature I studied growing up was English literature – novels by writers who lived in England and wrote about English life. From them I learned to find my way around London in my imagination. When I finally walked the London streets in 1962, I recognized names every time I glanced at a signpost. From Dickens I’d learned about the Inns of Court and Chancery Lane. I knew that Savile Row was filled with bespoke tailors, though I had only a vague idea what “bespoke” meant. Bond Street was where expensive jewelry was purchased by upper crust people who visited expensive doctors on Wimpole Street. Carnaby Street was where fashionable young people bought the latest fashions. As a newspaper reporter, I revered Fleet Street, where the great London dailies were headquartered.

The BBC world news, which in New Zealand we listened to on the radio every day, opened with the chimes of Big Ben, the clock at the Palace of Westminster, where the British Parliament met. I knew the sound, but still could write in amazement to my parents: When Big Ben strikes the whole street reverberates.

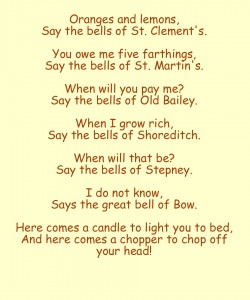

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

Here’s a Wikipedia page that includes a recording of the St. Clement Danes bells.

I wrote in my notes:

[V]ery difficult not to associate names of places in London with famous songs about them – find myself starting to hum the songs as I read the names.

We went to Buckingham Palace, of course, and I thought of my childhood book-friend Christopher Robin:

They’re changing guard at Buckingham Palace –

Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

Alice is marrying one of the guard.

“A soldier’s life is terrible hard,”

Says Alice.

My memory of those first few days in London is a sense of wonder and excitement as places became real. At the same time, there was a disconnect. I had to let go of expectations that special buildings, Sir Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s, for instance, were set off from other buildings, up on a pedestal, giving off a radiant glow. Reality was grimy walls and a crushed cigarette packet in the gutter. I wrote:

Peculiar sensation frequently of almost having been here before – not the usual one, connected with place, but connected with names – so familiar, and the outlines themselves so familiar, except that until now we had not known how they stood in the context of the rest of the city. –so this is Big Ben – so this is St. Paul’s – and we know they are, we have always known them, but we did not know that we would find them just here, with this office building on this side, and that park or square on the other. To walk down to the Embankment, and just happen to come upon Cleopatra’s Needle, standing so casually by the river. Somehow I had expected the great tourist attractions to be set apart, and gazed at always in awe. It is a jolt to realise that millions of people live and work alongside them every day of their lives, and take them so much for granted that they hardly see them. They leave the gawking to the tourists, who pour in by the busload, scatter their trash, and depart. The permanent thing is the life that goes on all around these not so very sacred objects, and of which they form a part.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Navigating the spider web

When Tony and I finally arrived in London after our weeks-long journey, our college friends Bill Moore and Robert Ludbrook met us at Waterloo Station. I felt like hugging them both, but thought they might be embarrassed, I wrote in my notes. New Zealand men of our time did not go in for overt displays of emotion.

An early 20th century view of Waterloo Station. It looked much the same in 1962. Image from http://www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/

Robert spoke of his and his wife Miriam’s “traumatic experience” when they arrived. They sat for three hours in the huge Waterloo station, not knowing whether they were on the right platform, not sure what to do, or even if they could get to Derby, in the middle of the country, where Miriam’s parents lived. Their ten-month-old baby was crying from hunger – none of them had eaten for three hours. They knew no-one in the city. “I decided then that no-one I called my friend should suffer the same fate,” Robert said.

Waterloo Station is part of a transportation network that on a map looks like a giant spider web with the heart of London at its center.

The trains link to London’s famous Underground system, with which I became very familiar in the next few weeks as I searched for short-term accommodation while Tony job-hunted. I found these notes in my black filing cabinet:

Several days [after our arrival] I returned to Waterloo, and could not remember ever having seen the concourse of the station before, yet we must have passed through it on our way to the underground platform. I can remember the way the train came into the main platform – rows of long platforms jutting out into the track, with the entrance at the head of them, and the high wrought iron and glass ceiling, very dirty, overhead.

And I can remember standing on the underground platform, although that memory rapidly becomes confused with standing on other underground platforms, all confusingly similar. Always the same smell, compounded of dust and disinfectant and human bodies, always the same roar of the escalators, the same draughts of air rushing in or out, and the airless feeling when a train has passed, the rattle and screech of the trains grating on the ear-drum and jangling the nerves. The hypnotic movement, grinding to a halt at stations, and the doors swishing open. Some go in and some go out, but they are always the same people.

It is very easy to miss your own station if you do not concentrate very hard. The signs are easy to follow – in the station itself you do not get lost unless you are very blasé and think you know where you are going – but all the stations appear exactly the same – it is just that in each the maze of tunnels is different. But once on the right train you feel that you are safe, that you can relax for a while from the struggle of finding your way about. This is the most dangerous of all, as before you know what has happened, the train will have swished past your station while you were still dreaming.

Stereotypes and misconceptions

When I lived in England in the 1960s it bugged me that, when they learned where I was from, people would typically have one of three responses:

1) They had no idea where New Zealand was.

2) They thought it was part of Australia.

3) They knew of it as that pastoral paradise they’d dreamed of emigrating to when they were younger.

Reading my old notes about coming to England in 1962, I realize that I too had huge misconceptions about what my new home would be like. Here is the account of our arrival:

First view of England – not counting faint views through the foggy channel – picturesque houses of Isle of Wight – only we thought it was Southampton and decided England must be charmingly antique and folksy, with church spires peeping through the trees and glowing green fields running down to the sea. but we were a little perturbed that we couldn’t get our geography right. Fascinated by the light – very soft, still a little hazy after the rain and fog of the day before, but with the sun coming through in pale golden streaks.

Our ship anchored off the Isle of Wight and passengers were sent ashore by tender. We managed to miss the boat train by being held up at Customs – a fuss over a lens Tony had bought in New York. But were well looked after by the railway porters, who rushed to get us into a taxi to catch the same train at the central station. On the way, the taxi-driver casually pointed out the old Roman wall of the town. As we gazed in amazement at something 2000 years old, and taken for granted, we began to realize the sense of history about the place, which confirmed even more the feeling of newness about New Zealand. My notes continue:

As the train pulled out of the centre of Southampton we discovered the slums. Obviously not the worst of the slums, but up till then we haven’t really believed that they existed, although we could mention them matter-of-factly. England from New Zealand looked a golden land, a land of opportunities, a land that housed the rich heritage of the old world. It definitely did not mean rows and rows of dreary brick buildings exactly alike, and behind them rows and rows of exactly similar yards, with blackened paling fences and rubbish tins. But occasionally we recognised the cry of a human spirit – from among the debris would rise a patch of golden daffodils dancing in the pale sun, cultivated by loving hands. And for a time we passed through farmland, with pussy-willow growing fat by the railway track, and small boys ambling cheerfully by hedges. Even one or two thatched cottages and barns, and we felt with a sentimental rush that we really were in England. But as we neared London the houses grew thicker and more dreary, their bricks blackened with smoke and soot, their monotony more grey. But even here people were making the best of their situation with window boxes full of bright flowers.

As well as misconceptions, I had opinions. I was amused to find in my notes that, with no knowledge of English social attitudes and no background whatsoever in urban planning, I laid out an argument about high density housing:

I have not yet resolved the problem of what is the best form of high density housing for such a city. Most people are housed in these old row houses, a monotonous block, but at least with some little bit of ground, however filthy and untidy, that they can call their own. The other alternative seems to be tall apartment blocks in their own parks. The disadvantage of these seems to be that the people shifted into them lose their sense of community – they no longer feel that their home is their castle, for they share it and its services with dozens of other families. I would feel the lack of a bit of ground of my own to cultivate, or just sit in. A semi-public park is all very well, but it gives no opportunity for creative contact with the earth. I have seen a few modern blocks of row houses, some of which are quite pleasant, but others will obviously become the future counterparts of the present monstrosities – pleasing to look at now because they are new, but once the newness has worn off little of artistic value will remain. Others, particularly a small block seen near Primrose Hill, had a cheerful friendly atmosphere that appeared more durable.

Ah, the certitude of youth.