Archive for the ‘architecture’ Category

The appeal of the picturesque

I’ve been wondering: what is it about an old house or barn that appeals so much that we describe the scene as “picturesque.” The question came up as I reread a January 1970 letter to my parents describing the purchase of a house in Cupertino, CA. Our new home was a typical early 1960s tract house with scalloped trim and prominent garage. The place was certainly not picturesque, but it was within our price range. I wrote:

It’s a very nice little house – 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, big sitting room with dining area at one end, small family room opening to a neat little kitchen, 2-car garage with laundry facilities in it. Very attractive inside, though not very prepossessing from the outside. However, this is just a matter of landscaping – other houses in the street are just lovely, but the garden of this one is just bare grass.

Looking back on that time, what comes most vividly to mind is another house I saw while house-hunting, a charming old farmhouse dating from the time when the Santa Clara Valley was so full of orchards it was called “The Valley of Heart’s Delight.” As I walked through with the realtor, I paused in what must have been a utility porch and mud room. The unfinished walls of the room were black with mold. The realtor shrugged when I pointed it out. The price was right, but I chose not to make an offer.

There’s a significant difference, of course, between the picturesque, which has been defined as that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture and a habitable structure for humans. But what is it in the human psyche that is drawn to the antique? Rummaging around on the web, I found quotes such as:

(esp. of a place) attractive in appearance, especially in an old-fashioned way

A picturesque place is attractive and interesting, and has no ugly modern buildings.

My friend Sandy Peters says it well. Commenting on a Portola Art Gallery exhibition of her husband Jerry Peters’ paintings of old battered trucks in rural settings, she wrote: They demonstrate how the beauty of nature blends seamlessly with the wisdom of age.

However, with age comes death. When we first moved to Mendocino seventeen years ago, a cabin stood among the trees along Highway 128, not far north of Yorkville. Its bare board were gray with age, the sway-backed roof shingles covered with moss. Over the years, the roof has slowly caved in, until now the cabin is a jumbled pile of boards. At first it was picturesque. Now when I drive by, I am sad.

A long, slow saga of first-time house buyers

In 1964 my husband Tony came into an inheritance, enough to put a down-payment on a small row house in a village on the outskirts of London. From first placing a ?50 holding payment on a partially-built structure to actually moving in took seven months. Today, with the purchase, remodeling and/or building of four subsequent houses behind me, I read my letters to parents from that period with wry sympathy, thinking how universal is the impatience of a young couple buying their first house.

The first letter in the series has a page or more of excited detail.

11 May 1964

… though still with the nagging doubt that it is all too perfect, that something is sure to go wrong. Points in favor: a brand new house within our price range (rare), architect-designed with imagination (also rare), less than a mile from Tony’s job, practically in the country with a charming view over open fields to woodland, closer to London (20 minutes by fast train to Waterloo) and won’t be finished for three months by which time we should have the means to pay for it…. Small, of course, but with ingenious use of space and attractive layout …

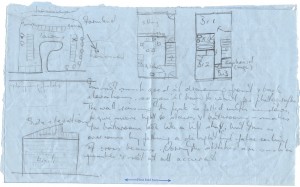

When I was growing up, my mother filled binder after binder with house design ideas and plans. We (my parents, three children, and succession of boarders – aunts, uncles, and family friends, often two at a time) lived in a rental Craftsman bungalow built about 1910: two bedrooms and a sleeping porch accessible only through the parents’ bedroom and through a laundry room in which a toilet was installed late in our tenure. (Before that, we used the outhouse back in the yard.) Mum eventually built her dream house when I was about thirteen. In the meantime, I learned a lot about building design and became very familiar with architectural drawing and its symbols. I drew her a sketch:

After a month of marking time, and a thickening correspondence file, a tirade about a building society (English equivalent of a mortgage company) to whom we had applied:

8 June 1964

… the building society wouldn’t consider our house for a mortgage because it was too contemporary in design – they stick doggedly to the deadly dull conventional things. We saw one the other day, part of an estate quite near here – good solid brick, appallingly bad planning, and claustrophobically tiny windows. Mortgages no bother.

A month later, good news on the offer of a loan from another building society. However, letters for the next several weeks report a battle with the developer:

30 July 1964

… One of the hazards of a speculative development – they are very reluctant to depart from the standard model, which in this case is decidedly murky – masses of dark grays, black, browns & blues. I’m getting a bit fed-up – sick of looking at samples & doing sums – I want some action round the place.

8 August 1964

… ran into trouble over the alterations we wanted to the colour scheme – we were met with a blunt ‘take-it-or-leave-it.’ However, eventually Tony rang up & told them they were a lot of bloody-minded so & so’s, & managed to get the most important concession – the colour of the tiles on the floor. The rest of the detailing we shall probably have to rip out & replace as we can afford it. Infuriating, but the housing situation being what it is, we daren’t tell them to go to hell.

Inevitably, construction delays kept postponing the finish date for the house:

26 Sept. 1964

We went up to London on Tuesday to sign the lease & mortgage documents for the house. Exciting, but still somewhat unreal. I am ceasing to believe in the existence of the house, and find it rather unsettling to go over every other weekend or so & find they have done a tiny bit. Still no idea when we can shift in – it will probably be weeks yet.

8 December 1964

It is still hard to believe that we have actually moved in. Up to 9:15 on Friday morning, with the carrier already piling boxes into the van, we still didn’t know if we could – it all depended on the cheque from the building society being in our solicitor’s post. A strange, unreal situation to live through. However, talking to some of the other people who have moved in, they seem to have had much more trouble than us, so we must be thankful.

Anyway, in all the chaos of cancellations, postponements, etc., it was too much trouble to cancel our housewarming party, so we held it as planned on Saturday night. The earliest arrivals were detailed off to put up curtain rails, shift packing cases from the middle to the sides of rooms, etc. Quite a successful party, I think. About a dozen people (& kids) stayed overnight, dossing down wherever for what was left of the night – we got to bed about 4 am, & a few more people dropped in for brunch the next morning. Needless to say by today we are both pretty worn out, but the house is more or less habitable. Strange what an effort, both physical & mental, to make a shell filled with boxes into a habitable room.

An advocate for junk heaps

Cover and invoice of a 1964 informational booklet, “Creative Play” published by Paul & Marjorie Abbatt, Ltd. Image from Pinterest

By the time I interviewed him in 1963, Paul Abbatt and his wife Marjorie had spent thirty years as advocates for the importance of play in the development of young children and for the betterment of children’s toys and playing facilities. Toys commissioned by their toy company, Paul and Marjorie Abbatt Ltd. of 94 Wimpole Street in London, won prestigious international awards for their good quality and design. Paul Abbatt, whose chief interest was in ‘the ethos behind the business,’ delivered lectures and contributed to academic and professional journals on child development.

In 1963, Abbatt was focusing on outdoor playgrounds for older children. He commented that

“…as a society becomes more urban and industrialised, it becomes more and more hostile to the child and its needs. As buildings are packed closer and closer together, available sites become too valuable for industry, or for car parks, to be used for children’s playgrounds. Even the upper class child with a garden of his own is no better off, for custom demands that his parents keep their grounds neat and spotless, and the child has no opportunity for such fundamental activities as building a den, or digging down to Australia.

In keeping with the stereotypes of his time, by older children he meant older boys, assuming that a girl would be “already a mother with dolls, kitchen, a little house of her own.” The interview continues:

Mr Abbatt believes that the solution to the needs of the older child can be found in the adventure playground. The first of these was built several years ago in Copenhagen, where the designer, instead of putting in the usual concrete shapes, swings and slides, filled his playground with builders’ junk. The playground was a great success, and was copied all over Europe. Some cities produced old cars, or traction engines, used tires, and even an old boat.

The first experimental playgrounds, with their carefully manufactured playing facilities, had not been a success. The children were interested at first, but quickly gravitated to the streets just outside the playground, where they were closer to the real life that they knew. But when the material was provided on the sites for them to build their own dens, they could create their own world inside the playground. “Building a den seems to be fundamental to children’s play, and other activities develop round the original den,” said Mr Abbatt. In Zurich, for example, the gang who inhabited one playground built up such a community spirit that they had their own bank with its own play money, a duplicated magazine, an antique shop, and even a farm with a dozen ducks on a man-made pond. When each gang deserts the playground, as they eventually do, the dens are pulled down, and the next gang to come along starts from scratch with the pile of junk.

In the meantime, in Copenhagen, the first adventure playground has become something of a showplace for visiting social workers. The grounds have been tidied up, and the rough dens turned into pretty villas. The visitors look and admire, but the children no longer come.

Similar problems affect playgrounds in Britain. They are normally noisy, untidy, derelict places, a disgrace to the neighbourhood of neat houses with even neater gardens. So local residents complain, and the council tidies up the playground. “In doing so, they destroy the urge for creative activity that the previous junk-heap gave to the children,” said Mr Abbatt.

In preparation for a conference of the International Council for Children’s Play, which Abbatt helped found, he is making a descriptive survey of children in Britain.

He has invited parents to write and tell him what their children do, and, since small boys particularly are notoriously uncommunicative about the activities of their gangs, he is also seeking information from policemen, schoolteachers, traffic wardens, and others who see the children outside their homes. Already the response from parents has been overwhelming.

He hopes that the survey will provide town planners, architects, and designers, with information on what children really want out of their community.

In a note to my editor, I promised a follow-up when the survey results were in. I’ll talk about that in my next blog piece.

The last time I saw Paris

An old letter from my black file cabinet brought back memories of a brief vacation in Paris in 1962. Rereading the headlong, crammed-onto-the-page text, I hear again the breathless voice of a wide-eyed young traveler falling in love with the city of light.

I’ve not been back to Paris. It’s likely I never will. But, as in the old Jerome Kern song, I’m happy to remember her as I saw her back then.

Listen to Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

singing “The Last Time I Saw Paris.”

Windsor, 24 Sept

Dear Mum & Dad,

Breakfast tray at our door each morning: croissants with butter and jam, café au lait–the height of luxury.

Back home in England again, and not particularly pleased to be back to these bleak autumnal mists, and a real stinker of a cold to go with it—first cold I have had for ages. We had a wonderful week in Paris, and fell in love with the city. Left very early Monday morning—rose before the sun, about 5 am, and took off at 8 in a Caravelle, a very fast French jet plane, which landed us in Paris before 9 – though it was after 10 by the time we got to our hotel, which was in a little side street off one of the main boulevards. Rather noisy, at least for the first night, as it was close to the great city market, which does its business in the small hours of the morning. The second night we didn’t even notice it. Nice room, with a balcony from which we could watch all the goings-on in the street below—most entertaining. We spent practically every day walking—the number of miles must be pretty high. First morning we went down to the old centre of the city, the Île de la Cité, an island in the Seine, and had a look at Notre-Dame—I hope you got the postcard I sent you of it. Spent the rest of the day pottering round the island, along the banks of the river to the Tuileries, and back by a more or less circular route to the hotel. The next day we went up to the north side of the city, to the hills of Montmartre—fascinating streets, most of them ending in steps, somewhat like parts of Wellington, and with graceful balconied buildings with the plaster peeling off. About midday we went out to the woods of Boulogne, a huge park just out of the city, where we watched workmen playing at bowls in their lunch-hour. It is a sort of grown-up marbles, played with heavy steel balls that you throw to knock out the kitty. Then we went back to the Arc de Triomphe and walked down the Champs Elysees—lots of interesting shops, and the wide street incredibly tightly packed with vehicles—you look down the street and you see nothing but a sea of car roofs. Traffic in Paris is very thick, very, very fast (no speed limits) but amazingly well organized. Pedestrians beware though—they are very much second class citizens, and boy do they hop when the traffic starts to move. Anyway, back to Tuesday—later in the afternoon we went over and had a look at the Eiffel Tower—a remarkable piece of engineering. We didn’t go up it, however—we had already seen enough views of Paris from above, and weren’t very keen on its reputation for swaying.

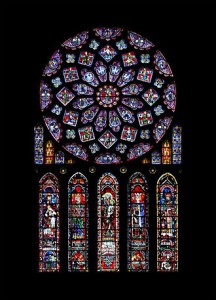

The next day we met my college friend John Wilson, who is at present living in Paris, and he took us out for the day in his little car, one of the new utility model Citroens. You may not have seen them in New Zealand. A chopped-off little bug, a bit ugly, very mass-produced, but able to go anywhere, very cheap, and very comfortable to ride in. There are thousands of them in Paris. Went first to Versailles, to look at the palace where the king and Marie Antoinette were taken from to have their heads chopped off. A most impressive building (though we didn’t have time to go inside), and the gardens are incredibly beautiful, in a cool, formal sort of way. Mostly vistas of fountains and pools, with statues, with a few formal flower beds, and woods beyond, laid out with a grace and elegance unknown to these more democratic times. We could have stayed there just wandering all day, but had to get going again, through side roads and quaint little villages. We had lunch in one, at a street café in the village square, just outside the gates of a very charming old chateau, whose towers were reflected in the canal close by. Then on to Chartres. The cathedral stands on a hill overlooking the plain, where there has been a church since the third century. This one was built in the 13th century, and was remarkable in that, except for part of one tower, which is noticeably odd, it was completed in thirty years. Outside very elaborate and impressive relief carvings in the porches, lots of gargoyles and what not.

You go inside, and it seems at first quite dark. Then gradually, as your eyes get used to the light, the huge pillars begin to appear, lit up by a pale greenish, strangely luminescent glow. Then you look up, and are practically dazzled in the burst of red and blue and green. The stained glass windows of Chartres are said to be the most magnificent in the world, and I can well believe it. To the north, south and west are huge rose windows, and all around are arches, each closely worked with many little pictures of saints, in incredibly fine detail. The result is a blaze of pattern and colour.

Then back the sixty miles to Paris, through wide open fields—no fences in this region, and the land is fairly bare of trees, and with a very gentle swell. It is a grain growing area—lots of harvesting machinery, and everything a beautiful golden colour—even the soil is the same colour as the wheat stubble. The next day we went to the Louvre museum, or at least to a small annexe, the Impressionists gallery—Van Gogh, Renoir and co., and discovered again the beauty of many of the paintings that we had thought a bit hackneyed in reproduction—things like Degas’s ballet pictures for instance—very beautiful and subtle in the originals. Spent all morning there, and in the afternoon walked over to the other side of the city, to see the UNESCO building, a very fine modern building. Our favourite part of it was a Japanese garden in the grounds, a little area of different levels and contrasting textures of stones and gravels, a stream and a pond, and a few bushes. Sounds rather stark and uninteresting to describe, but the result was charming, and very peaceful and relaxing. Friday back to the Louvre, to the main museum this time, but when you think that each of the wings of this is about a mile long, with several intersecting galleries about half a mile across, and all several stories high, you will realise that we didn’t see much of it, and even what we did see—mostly Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, there were so many fascinating and beautiful things to look at that we didn’t do them justice—excuse for going back! Later in the afternoon we had to think of getting ourselves back to the airport. Bought some beautiful (smelly) French cheeses from one of the many street markets, then got out to the airport to catch our plane at seven. Wonderful to see the lights of London as we flew over the city—when we got under the cloud, that is. Very exhausted by the time we got home, but still wouldn’t mind doing it again. Though went into London yesterday, to see [our friend] Bill, an exhibition at the Tate, and a concert at the Festival Hall, and decided that London was rather lovely too.

Vive la France! Love, Maureen

Plumbing crisis brings neighbors together

Windsor Castle in the snow, January 1963. We lived in the town below the castle. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

The winter of 1962-63, my first in England, was the coldest Britain had known in over 200 years. First the fog crept in. My nostrils tightened against the thick yellow damp, sour with the smoke of coal fires and diesel trains. As November wore on and the cold deepened, fog froze into hoar frost that thickened daily on the power lines until they resembled sagging ropes.

Snow began the day after Christmas. All January it snowed and froze and snowed again. Transportation systems ground to a halt. The River Thames froze over. The inside wall of our apartment kitchen, wet since November and already black-mottled with mildew, glazed over with ice. On the outsides of buildings, ice congealed around plumbing outlet pipes like candle wax dripped from lighted candles. Water pipes froze and burst. The clatter of buckets as the water truck made its rounds became a familiar sound in our Windsor neighborhood.

Windsorians walk on the frozen Thames.

A view towards Windsor Bridge photographed on 24 January 1963. Image from the Royal Windsor Website

A side benefit of the bad weather was that we got to know our neighbors. Here’s a letter I wrote to my parents:

23 January 1963

I think we must be drifting into another ice age – the weather here continues to get colder every day. All sources of fuel – coal, gas electricity, and even paraffin, are in short supply, and everyone is fighting a losing battle against frozen pipes and general seizing up.

We had our fun and games over the weekend. We were woken fairly early on Saturday morning to terrific shouting and hammering on the door. We staggered out, to find that the Hoopers were being flooded out – their kitchen was an icy pond, and water was pouring through the light fitting in the ceiling. We turned off all the taps we could find, someone somehow found a plumber, and after he, Tony and Peter [Hooper] had hacked their way through the several inches of ice outside the front gate, and even more ice on top of the valve, they managed to get the mains off. Next thing we tried to get in touch with Stan Fricker, from whose flat the water was coming – he was at work, and we had visions of him coming home to a complete flood. By the time he arrived we had swished most of the water out of the kitchen, and had got all the heaters we could find in to dry it out. So we all trooped up into Stan’s bathroom, which is directly above the Hoopers’ kitchen and, to our surprise, found very little trace of water. We bailed the solid chucks of ice out of the bath, which had been frozen up for days, and Stan and Tony got to work on the floorboards, which were suspiciously damp. They managed to raise a couple, and discovered that the break in the pipe was right underneath the bath, which had been very recently closed in and modernised with plywood, fresh paint, and what not. A brute to get at.

The next thing to do was to find a plumber to fix it – easier said than done – “Oh no, love, we couldn’t possibly let you have one till Monday.” I don’t know how many pennies we spent on phone calls over the weekend, but at fourpence a call we went through several shillings. But we still couldn’t get a plumber till Monday, and late Monday afternoon at that. So we borrowed buckets of water from a neighbor, and puddled along with little dribs of washing where necessary, keeping most of it for drinking. It was pretty messy. At least in the old days they had facilities in keeping with such conditions – but try using a modern-type lav when you have nothing but half a bucket of dirty water to flush it with. That was the first thing that Margaret [Hooper] did, with great ceremony, when the plumber finally managed to get the water on again for us on Monday evening. Our lav had to wait a few hours longer – the remaining water in it had got so iced up that it had to be very carefully thawed before anything would move. And we still can’t have a bath – the outlet pipes in the bathroom are frozen up and, according to the plumber, that will just have to wait till the thaw.

The kitchen outlet, which comes down in the same place – down the outside wall on the coldest side of the house, now shows signs of doing the same thing, which would be choice. I am shortly going to do some washing, and hope that the gallons of hot water from the tub will deter it. Still, we could always throw our slops out the window – if we could unfreeze the windows enough to open them, that is. Might as well be really primitive.

We are getting rather advanced ideas on the proper requirements of a house in this climate – they do not agree very much with the conventional buildings most people live in here. Definitely central heating, double glazing, and interior plumbing.

Translucent angels

The glass artist John Hutton was on the list of New Zealanders living abroad that my editor at the Christchurch, NZ Press handed me when I left the paper in 1962. “He’s been working for years on a project for the new Coventry Cathedral. Go check out how it’s going,” he said.

Also known as St. Michaels, the original cathedral in Coventry, England was constructed between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. It was gutted by incendiary bombs during World War II; only the tower, spire, the outer wall and the bronze effigy and tomb of its first bishop survived. After the war, a decision was made to build a new cathedral and to preserve the ruins as a constant reminder of conflict, the need for reconciliation, and the enduring search for peace. The architect, Sir Basil Spence, proposed that the new cathedral should be built alongside the ruins, the two buildings together effectively forming one church.

Spence commissioned many magnificent art works for the new modernist building. Hutton’s contribution was to be a great glass screen for the west end of the new cathedral.

This image of Hutton’s great glass screen was posted by ashleyniblock on http://www.vortis.com/blog/

Unfortunately, the text of my interview is lost, but I still have a letter I wrote about our visit to Hutton’s studio near London:

May 9, 1962

One of the vases made by Hutton for sale at Coventry Cathedral. It is decorated with figures which appear among the images in the Great West Screen. It is now in the University of Warwick Art Collection.

Another artistic experience of a quite different sort was on Monday – we went out to interview John Hutton, a New Zealand artist who has made the great glass screen for Coventry Cathedral, which is to be consecrated this month. The panels are engraved with saints and angels, in a very bold scribbly style that nevertheless has a rich Gothic quality about it. We were very impressed, and also with his other work that he has at his studio – more glass work, but also paintings, and many other media as well. Just wish we had a hundred pounds to spare – he is making a series of vases, each engraved with two of the angels, which the cathedral is selling to raise funds.

Revisiting this story feels particularly relevant today. From the window of my office at the Christchurch Press, I used to look out at ChristChurch Cathedral, which was destroyed in the earthquake of 2011. Arguments are still going on about whether to rebuild or replace a building that was the physical and spiritual center of the city.

Discovering the familiar

When I first went to London, I already knew it, or thought I did. The literature I studied growing up was English literature – novels by writers who lived in England and wrote about English life. From them I learned to find my way around London in my imagination. When I finally walked the London streets in 1962, I recognized names every time I glanced at a signpost. From Dickens I’d learned about the Inns of Court and Chancery Lane. I knew that Savile Row was filled with bespoke tailors, though I had only a vague idea what “bespoke” meant. Bond Street was where expensive jewelry was purchased by upper crust people who visited expensive doctors on Wimpole Street. Carnaby Street was where fashionable young people bought the latest fashions. As a newspaper reporter, I revered Fleet Street, where the great London dailies were headquartered.

The BBC world news, which in New Zealand we listened to on the radio every day, opened with the chimes of Big Ben, the clock at the Palace of Westminster, where the British Parliament met. I knew the sound, but still could write in amazement to my parents: When Big Ben strikes the whole street reverberates.

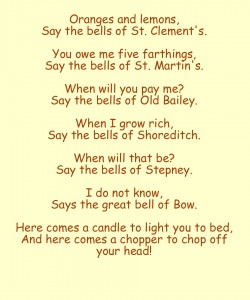

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

Here’s a Wikipedia page that includes a recording of the St. Clement Danes bells.

I wrote in my notes:

[V]ery difficult not to associate names of places in London with famous songs about them – find myself starting to hum the songs as I read the names.

We went to Buckingham Palace, of course, and I thought of my childhood book-friend Christopher Robin:

They’re changing guard at Buckingham Palace –

Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

Alice is marrying one of the guard.

“A soldier’s life is terrible hard,”

Says Alice.

My memory of those first few days in London is a sense of wonder and excitement as places became real. At the same time, there was a disconnect. I had to let go of expectations that special buildings, Sir Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s, for instance, were set off from other buildings, up on a pedestal, giving off a radiant glow. Reality was grimy walls and a crushed cigarette packet in the gutter. I wrote:

Peculiar sensation frequently of almost having been here before – not the usual one, connected with place, but connected with names – so familiar, and the outlines themselves so familiar, except that until now we had not known how they stood in the context of the rest of the city. –so this is Big Ben – so this is St. Paul’s – and we know they are, we have always known them, but we did not know that we would find them just here, with this office building on this side, and that park or square on the other. To walk down to the Embankment, and just happen to come upon Cleopatra’s Needle, standing so casually by the river. Somehow I had expected the great tourist attractions to be set apart, and gazed at always in awe. It is a jolt to realise that millions of people live and work alongside them every day of their lives, and take them so much for granted that they hardly see them. They leave the gawking to the tourists, who pour in by the busload, scatter their trash, and depart. The permanent thing is the life that goes on all around these not so very sacred objects, and of which they form a part.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes