Archive for the ‘food’ Category

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

Gifts of an old tree

Ripe apricots on a tree. Image from Nature & Garden.

The Cupertino CA neighborhood where I lived in the early 1970s was developed about 1962 on the site of an old apricot orchard, the trees probably planted before the post-WWII boom of the 1950s transformed the orchard-covered Santa Clara Valley into Silicon Valley. The developers had left an apricot tree on each lot. Gnarled and picturesque, they provided welcome shade on hot summer days, and a harvest of apricots for those who loved them. Letters to my parents from two different years offer a glimpse of harvest time:

26 June, 1970

… Meanwhile, the apricots are getting ripe. We have started picking, and they are delicious. Several neighbours with trees (this used to be an orchard) don’t like them too much, so those of us that do are planning to get together and pick for drying. You have to have 65 lbs. of fresh fruit to fill a tray, and a local orchard will sulphur and dry them for us for $30 a tray – pretty cheap dried apricots!

Apricots drying in the sun at the Curry family orchard in San Jose, date unknown. Standing are Douglas and Howard Curry. Image from Lisa Prince Newman’s blog, For the Love of Apricots.

I still remember the fun we had at that orchard in Los Altos Hills. It had a long, open-sided shed with a work table running down the center. My friend Judi and I and other women of the neighborhood stood at the table, cutting or breaking open pound after pound of golden, honey-scented fruit and laying them on the drying trays. Beyond the shed we could see a stretch of bare earth where the big wooden trays of fruit lay open to the sun. About ten days later we returned and were presented with our now-dried fruit, shriveled, somewhat brown, but delicious. A year later:

26 July, 1971

I have also been busy coping with the apricot crop. Our poor old tree has really taken a beating this year. We lost a third of it in the spring with fire blight, and then came home one afternoon when they were just about ripe to find a huge branch crashed to the ground. The poor thing is just dying of old age, and we shouldn’t have let it carry so much fruit. I managed to salvage about 70 lbs. from the broken branch, which we took to a commercial orchard to be dried. They turned out very well this year. They shrink, of course, to a fifth of their weight, but 13 lbs. of dried apricots is a fair quantity. I have also bottled quite a lot, and made jam, and then we had a bright notion of drying another 30 lbs. at home and making wine with them. This is Tony’s project, and he has been having a great time with it. We came home the other night (after eating out with friends) to find that the yeast was working so well in one jar that it had blown the top off, and there was gicky apricot pulp all over the counter!

Decades later, when we finally opened a forgotten bottle of that wine, it was vinegar. Oh well … By then we were no longer living in Cupertino, so I don’t know how much longer that kind old tree lived. I hope its new humans gave it a dignified end.

A roof and a meal in 1968 dollars

While rereading letters dated early 1968 from California to my New Zealand parents, I discovered a conversation about the cost of housing and the cost of living generally. If you’ve seen the current astronomical real estate prices in the San Francisco Bay Area you will be mind-boggled at the numbers. For that matter, housing prices have also risen dramatically in New Zealand cities. (To take inflation into account, multiply the US 1968 numbers by 7.2)

The conversation started with mention that friends in the apartment complex where we lived had bought a house.

2 Jan. 1968

On Sunday we spent the afternoon at the J___s’ new house – they have managed to acquire a lovely rural acre running down to a creek – we are very envious.

26 Jan. 1968

You asked about the price of housing. Well, the J___s got theirs extremely cheaply, because of some easements on the property – power lines restrict building on one corner, and a road may possibly go down the side of it. Normally such a place would go for between $45,000 and $50,000 – they got it for under $35,000. Housing is generally pretty expensive here. If you want a genuine or potential slum you only have to pay about $18,000, but the vast majority of ordinary middle class suburban houses – about equivalent to the typical NZ suburban house – come in the range $22,000 to $28,000. New houses in this area, that is, the west side of the [Santa Clara] valley, are all $35,000 and up. Down payment is between 10%–25%. Which puts us out of the housing market for some time.

Just for comparison, what would an equivalent house in NZ cost now? The outer suburbs of Auckland or Wellington, for instance. It would also be interesting to compare costs of living – could you find out for me how much it would cost per week to keep house for a family like ours, for instance?

27 Feb. 1968

Thank you for the list of prices etc. Costs certainly seem to be fairly high. Your power bill is about the same as ours, and so is the telephone. Houses in NZ seem to be about half our price, but rents considerably lower – we are paying $160 a month, or $40 a week, and this is pretty reasonable for this area. To get a house we would have to pay $225 or more.

Your food bill is certainly much cheaper than mine. I have $40 a week for housekeeping, of which about $20 goes on groceries, $4 on fruit and vegetables, $5 on meat (and this is pretty frugal – we practically never eat steak, for instance. In fact, our standard of living hasn’t changed much from what it was in England.) The rest goes on miscellaneous sundries – sewing notions [I sewed all my own and the children’s clothes], postage, haircuts – at $3 a go for an ordinary cut it’s just well I don’t go in for sets, perms, etc., and the boys’ hair I cut myself.

…This seems to be turning into a grouch about costs, which is not really fair, as salary levels are comparably higher. At present we are managing to save about 10% of Tony’s salary, which is better than we have ever done.

Those new houses in Cupertino that in 1968 were selling for $35,000 are now listed at over $2,000,000. That’s eight times the inflation rate. Economists might say that’s the law of supply and demand.

A sisterhood of neighbors

Would she be able to watch my toddler for an afternoon while I went to a doctor’s appointment, I asked Margaret, my next-door neighbor in the block of new row houses we’d both recently moved into in 1965. An odd look came over her face, and a blush reddened her cheeks. A pause. “Actually, I have a doctor’s appointment that afternoon too.” Another pause. I don’t remember which of us said it first: “I think I’m pregnant again.”

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

Not having family in England to call on for help, I am forever grateful to this sisterhood of neighbors. Most of the women in our little close of twenty houses were stay-at-home mums with small children. We drank coffee together in the mornings and shared how our brains were turning to mush. Our children ran in and out of each other’s houses. We took care of each other.

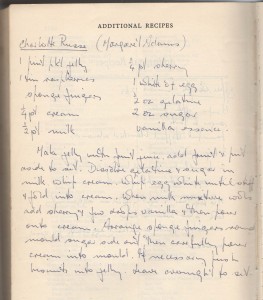

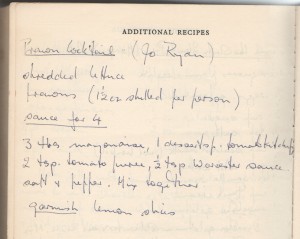

On the back pages of my English cookbook are two recipes, one for a Charlotte Russe from Margaret and a prawn cocktail from Jo, both classic 1960s recipes. I remember the occasion vividly. My husband Tony had accepted a position in California. We were waiting for our US green cards to come through –a nerve-wracking saga that I’ll write about sometime. Meanwhile, his prospective new boss was passing through on his way home to Denmark for Easter, and wanted to meet Tony. A dinner invitation was obviously required. But what to serve? In a panic, I turned to my sister-neighbors. They held my hand and helped me through planning a menu. Prawn cocktail to start, and Charlotte Russe for dessert. For the main course I probably served roast lamb, a traditional New Zealand staple.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

A season for love (and cake)

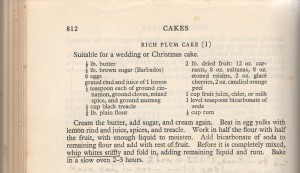

What I loved about living in England as a young woman in the 1960s was the traditions around the holiday season. On foggy street corners in London, vendors with portable braziers sold roasted chestnuts, hot in the hand, but so good. Butchers’ shop windows would fill with huge hams, neighbors’ kitchens be redolent with the aroma of figgy puddings steaming on stove tops. I would pull down the English recipe book my mother-in-law had given me and assemble ingredients for my Christmas cake: an assortment of dried and candied fruit, spices, juice, eggs, butter, brown sugar, treacle, flour, and the all-important dash of rum.

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

Making a proper English fruitcake is a multi-day affair. First, the careful preparation of the tin and timing of the baking so that it doesn’t go dry. My Constance Spry Cookery Book devotes several pages to these matters. Then the making of the cake itself. Several days later, in preparation for icing, the cake is brushed with a warm apricot glaze. My cookbook declares:

The object of this protective coating is to avoid any crumb getting into the icing and also to prevent the cake absorbing moisture from the icing and so rendering it dull.

Next comes the layer of almond paste or marzipan, rolled out like pastry and smoothed on with the palm of the hand. A day or three later comes the smooth base coat of royal icing, made by mixing egg whites and lemon juice with the sugar. When this layer is perfectly stiff and hard the decoration is piped on.

When we moved to California, I continued to make Christmas cake for a few years, until I realized that fruitcake in America is the butt of seasonal jokes and that my lovingly prepared cake sat in the pantry scarcely touched. I am grateful that until his death a few years ago, my late brother-in-law Derek Heckler, who lived not far away, continued to bake and share a splendid traditional cake.

As earth and sun roll toward another pausing time, let us remember dear friends and family members now gone, and reach out in love to those still with us. However you celebrate the season, may it be filled with the traditions you hold dear.

The red stain of near disaster

Whenever I see old blackberry canes, dark red as the stain of their summer juice, I remember blackberrying in England when my son was small, and a dark red guilt sweeps over me. I described our expedition in a letter to parents:

8 Oct 1965

We went blackberrying on St. Ann’s Hill, not far from here. Got a lovely lot—have been busy making jelly, pies, etc. David had a wonderful time—it was so sweet to see the solemn single-mindedness with which he set about collecting his berries—and he didn’t eat a single one until Tony offered him a handful—to comfort him when he tumbled down a slope into a patch of brambles.

Modern American parents would probably be horrified at how lackadaisical we young mothers in England were about supervising our children’s play. Once the daddies were gone to work, our little close of twenty-eight row houses was almost completely free of traffic. The kids, twenty of them under school age, ran in and out of each others’ houses and romped together across the grassy front yards.

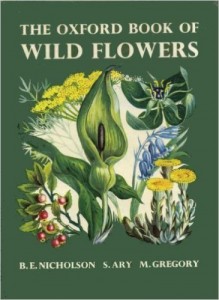

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

While Tony, who had come home from work for lunch, went to tell the mother of the other child what had happened, I tried everything I knew of to make our baby throw up. Nothing worked. We called an ambulance. Since I was within a week or two of giving birth to our second child, a neighbor, seeing the ambulance, came over to wish us well. I am still grateful that when she learned the story, she called the police, and still guilty it hadn’t occurred to me that other children might be involved. Some days later I wrote to parents:

Watercolor illustration by Barbara Nicholson in The Oxford Book of Wildflowers, Oxford University Press, 1960. Shown are: Comfrey, Common Mallow, Musk Mallow, Deadly Nightshade, Duke Of Argyll’s Tea Plant, and Woody Nightshade.

13 Oct. 1965

The police organised all the rest of the kids in the close whose parents couldn’t prove they were somewhere else that morning into another convoy of ambulances for a mass stomach pumping session. About a dozen altogether involved, of which four (including David) were confirmed cases, though they decided to keep the whole lot overnight for observation, just in case.

Meanwhile the newspapers had got hold of the story. We refused to see them at the hospital, but when we got home about 7:00—completely exhausted, & having had nothing to eat since breakfast—we were invaded by a posse of reporters. A highly garbled & exaggerated account appeared the next day. I suppose it’s not every day one makes the front page of the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, & the BBC News, but I shouldn’t care for the honour to happen again.

Anyway, the story ended well—all the kids were discharged the next morning, with none but the hospital staff any the worse for wear—in fact the sister-in-charge of the children’s ward where the confirmed cases were confessed that she hadn’t known that four such tiny boys could get so involved in riots and punch-ups all up and down the ward, and they were very pleased to see the back of them.

A day at a famous cookery school

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

As an engagement gift, my future mother-in-law gave me a copy of The Constance Spry Cookery Book. Constance Spry was well known in New Zealand, both for this book and for her several books on flower arranging. When I moved to England in the early 1960s, I was delighted to discover that I lived quite close to Winkfield Place, the school of cookery and domestic arts founded by Mrs Spry and Rosemary Hume, who was also co-director of the Cordon Bleu School in London. A hook for a story for my New Zealand paper was that a NZ girl currently attended the school, so I wangled myself an invitation to spend the day. Here’s what resulted:

A day at a famous cookery school

Even at first sight Winkfield Place is charming. It is a large, white country house, set in broad gardens on the edge of Windsor Forest. Inside, all is bustle and activity. About 100 girls are going about their regular classes: cookery, dressmaking, handwork, flower arranging, shorthand and typing, and another 60 local women are attending demonstrations on cookery and flower arranging. The girls normally spend a year at the school, with a few staying on for a fourth term to take the Cordon Bleu diploma, which is recognised all over the world.

The girls, each in shining white overalls and chefs’ caps, cook in classes of 10. From one kitchen came appetizing smells of spaghetti and baked apples. From another, risotto with a potato salad, and a hazel-nut meringue to be served with an apricot sauce. Miss Hume was found in another kitchen busily stirring whipped cream into a creamed rice pudding. A dish of chopped nuts was waiting to be sprinkled on top.

Later in the afternoon, Miss Hume gave a cooking demonstration. Lotte en mayonaise, tourtiere de boeuf, chicken mousse italienne, and chamonix, were the menu for her supper party. Translated, they were a fish mould gaily decorated with gherkins and chopped parsley, a tasty steak pie, a jellied mould of creamed chicken and shredded ham, and a magnificent dessert of meringue topped with a piped “birds nest” of chestnut puree and whipped cream.

Miss Hume is described by Mrs Spry in her book (which is jokingly referred to as “the bible” at Winkfield) as the authority from whom she obtained all the cooking knowledge she had. She is a tall thin woman, with a strong no-nonsense face, a shy smile, and a deft hand with the pastry. Her guiding characteristics are commonsense and a passion for economy: she believes that all food should be treated with respect, and that to waste it is a crime. She has become expert in parrying the comments of the more snobbish of her day class audiences. One woman, for instance, wondered why she did not use fillet steak in her pie, instead of the less expensive, and less tender, rump steak. Her reply was that fillet was too good for this sort of pie, which was a “cut-and-come-again,” and that the recipe called for a cooking time quite adequate to make the rump tender. Her final comment tactfully vanquished the snob. “I for one would be grateful for a piece of this pie,” she said.

The spirit of Mrs Spry lingers throughout the house. Although few of the present students ever met her, many of the staff, who are old girls of the school, recalled her engaging personality. They spoke of the dinner parties she used to hold on the bare scrubbed table of the diploma group’s kitchen, with the candlelight gleaming on the array of copper utensils on the shelf behind. They described with amusement the clutter of treasures in her flat, and the extraordinary leaps of her conversation. “You will remember, dear,” she would whisper confidentially to one of her students, in the middle of a discussion on current affairs, “that you must always clean out the bath when you get out of it, and hang the bathmat up to dry.” Many remembered her beautiful hands, and her great skill with flowers. With it went the ability to encourage her pupils. Mrs Christine Dickie, now co-principal of the school, described how she herself was never very good with flowers. “But Mrs Spry would come in with a great heap of flowers, and say, ‘Do arrange these for me, dear.’ I would struggle with them, but the result always looked a mess, and I would beg her to show me what to do with them. ‘What’s wrong with that, it looks fine,’ she would say, giving the whole bunch a little tug that made it exactly right. Then I would be rather pleased with myself, although I know deep down that she had done it.”

Mrs Dickie was with Mrs Spry during the founding and early growing pains of the school. “She had that wonderful gift of delegating authority,” she said. “She would forge ahead with some new project, with her ‘dogsbody’ (that was me) beside her, and when the groundwork was laid, she would say, ‘Now you take over – I have other things to do’.” The result was that at her death a few years ago, the staff, although they missed her very much, found that they could continue almost as if nothing had happened. Mrs Spry made provision for this in her will. She instructed that the existing staff were to run the school for three years. If they succeeded in keeping it going, they would be permitted to continue, but if in that time the school went downhill, it was to be closed immediately.

It says much for Mrs Spry’s groundwork, and for the enthusiasm that she had inspired in her staff, that not only has the school survived, but it has had to expand to cope with the increasing demand. There is now a long waiting list for places, and the day classes, about 60 women each on three days of the week, are filled well ahead of each term.

There have been a few changes in the character of the school, and these are ones that reflect an interesting facet of English society, the decline of the debutante. When the school opened, it was regarded as a finishing school for debutantes, as a place to acquire some skill in the domestic arts before coming out into society. To a certain extent this is still true, although of the 100 girls at present at the school, only four or five are potential debutantes, and the social whirl of a debutante’s life is viewed with some scorn by the staff. The others will take up a great variety of careers. Some will go from the secretarial course to office jobs. Many of the girls in the cookery course will go into institutional kitchens, some into private houses. Some will take up other careers, such as nursing. The really dedicated cooks are to be found in the Cordon Bleu diploma class, practically all of whom want to be free lance professional cooks, and spend many of their odd moments discussing the most suitable kit of kitchen equipment to carry with them, or the prospect of gaining experience among their friends.

There are still some girls who will probably not have to earn their living. For them the course provides a convenient stop-gap between school and adult life, in a place where they can learn to grow up pleasantly and happily, while at the same time providing themselves with a form of insurance in case they do have to keep themselves. For them it is also a safeguard against the increasing difficulty of finding domestic staff. Coming from homes where all the housework is done by servants, they realise that for themselves it may be a choice between the cooking and the dusting. The girls who attend Winkfield have plumped for the cooking.

The many names of bread

A cottage loaf. Image from Bewitching Kitchen

Living as I do in Mendocino, CA, I am blessed with access to excellent local bakeries offering a wide variety of breads. I was amused to find in my old black filing cabinet this article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about discovering there were more names for bread than “white” and “brown.”

Slindon Bakery’s website has many pictures of these traditional English breads.

A Loaf by Any Other Name

London, 1962

The shelves of a baker’s shop anywhere in New Zealand will be much the same—piled high with round-topped loaves in brown or white, square white sandwich loaves, and pre-cut wrapped bread, and although North Islanders and South Islanders may argue for hours over whether the broken half of the double loaf should be called a “half” or a “quarter”, they will usually be able to make themselves understood in any bakery.

Imagine then the confusion of a New Zealand housewife confronted with the window of an English bakery, filled with loaves in an incredible variety of shapes and sizes. Some of the shapes are wonderfully decorative. There will be long thin loaves and short fat ones, some decorated with grain and some with shining glazes. There will be complicated plaits and squat little knots, enormous swelling crusty loaves, and incredibly long thin rolls that look as if they have been transplanted from the Continent.

The vagaries of English custom have established different names for these traditional shapes from town to town, and sometimes even from shop to shop in the same town.

The biggest and crustiest loaf of them all is usually called a “farmhouse.” It is a tall white loaf, often bursting from a long crack in its top. It has a close relation in the “split tin”, which does not appear to be split at all, but merely a white loaf, again with a cracked top, baked in a narrow oblong tin. These loaves are not to be confused with the “Danish”, which is not baked in a tin at all, but rises as a large oval loaf, dusted with white flour, from a flat tray.

Then there are the more elaborate shapes, such as the “cottage”, often confused with the “farmhouse”. The “cottage” is made with two balls of dough, the smaller being set like a top-knot on top of the larger. Another even more complicated one is the double plait, which contains, as its name implies, two plaits of dough set one on top of the other.

Some of the small round loaves have fascinating names. There is a ball of rich wholemeal bread decorated with wheat grains, which is called, appropriately enough, a “round meal”, but the white ball, this time with a shining brown glaze, is known as a “cob.” This is reputed to be short for “Coburg”, but where this name came from few seem to know.

The origins of other names are more obvious. One delicious scone loaf, which is sold in quarter segments of a large flat disk, is known in England as “Scotch fare”. In Wales, however, they are sold as “Welsh babs”.

A small light white loaf with a shiny glazed crust decorated with diagonal slashes, and known as a “Continental”, has a large elder brother with various titles, but usually known as a “twist” or a “bloomer”. This odd name can cause difficulties, and it has happened that an order for “A large bloomer, thank you” has met with raised eye-brows from the shops that have not heard of this title. In most cases, it is safer to point: “That one over there” and then politely ask the name of the specimen as it is being wrapped up.