Archive for January, 2019

A legacy of crocheted lace

A comment in an old letter to my mother catches my eye:

March 1, 1971

I can’t remember anything about that bit of crochet, Mum, but I guess it probably is mine. Now it will sit in my workbox for years!

Do I still have it? I open the Cadbury’s Chocolate box that holds my collection of crochet hooks and sundry balls of crochet thread. On top sits a small piece of lace, obviously the beginnings of an ambitious project. Was it the piece that cluttered Mum’s workbox? Probably.

The art of crochet was honored in my mother’s family, passed on, like all domestic arts, from generation to generation. The most noted expert was my great-grandmother, Sarah Jane Caundle, whom I met a few times when I was a child. She was born in 1864 to Irish immigrants on a New Zealand goldfield. In a reminiscence my mother wrote:

Outside the back door [of Grandma’s house] in the sun was a stool to sit on. Across the yard in a shed that housed the wash house with its copper and wooden tubs with the toilet next to it. Grandma washed the clothes in the old way with a well-stoked fire under the copper to boil the sheets, etc. The tubs for the rinsing and blueing with a hand-turned wringer between them. While visiting as a small girl I was being taught how to crochet. Trying to make my doll a pink woolen petticoat like the ones Grandma made for us. Something would not go right so I called for assistance. There was Grandma coming across the yard at her usual jog-trot wiping the soapsuds off her arms on her apron (Must always wear an apron) to sort out my muddle. The picture is still so clear in my mind.

… As we grew older we were given doilies and crochet-edged linen for our “box.” At each 21st birthday each granddaughter was presented with an afternoon tea cloth with a wide edge of crochet lace.

Before she died in 1951, Great-Grandma Caundle had started making doilies for her great-granddaughters. I missed out, but inherited a piece of her work from my mother. Fascinated by Mum’s stories about her grandmother’s life, I put together a poem:

Great-Grandma’s Doily

Early afternoon, when chores were done,

Great-Grandma put her feet up on the kitchen couch

and gave herself an hour with crochet hook and thread

to figure out the sequence from a photograph—

chain and double loop and treble—

the mathematical progression of the rounds

revealing patterns satisfying in their laciness.

She learned the art at her mother’s knee

in the dirt-floored hut at the Puriri claim.

Her mother learned it from her Mam

back in Ireland before famine memories

and rumors of gold in the far-off colonies

took Bernie Donnelly and his new young wife

adventuring across the world.

There was a dame school at the diggings.

Great-Grandma might have gone some days

but not enough for fluency in letters.

She had sisters and brothers to mind,

manuka-twig brooms to fashion for the floor,

clay to fetch for the hearth’s weekly whitewash of mud.

She entered service as a housemaid at eleven.

Later came marriage and children of her own,

nine of them, then grandchildren to care for.

All this time persisting in her art,

gifting to daughters and grand-daughters

lacy linens for their marriage chests.

I have one doily, handed down, an oval of white linen

edged with a crocheted frill of tulips in a row,

each stitch pulled neat and tight, a testament

to discipline and practice, and the will

to make time for her art.

A spat in slow motion

A spat between parent and adult child is different when conducted on flimsy blue international air letter forms. For one thing, it happens in slow motion: weeks pass between riposte and retort. For another, it’s solitary: neither side can see the angry tears of the other. And it’s documented; that is, if letters are kept. My mother kept all mine, and gave the bundle back to me. I constantly regret that I didn’t keep hers, so have to guess at the comment to which a letter of hers or mine would have responded.

A typical example happened in late 1971. Decades later, as I read through my old words, I recognize patterns of individuation familiar to every psychoanalyst.

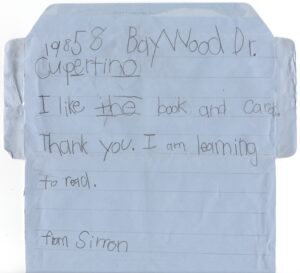

It started with a postscript to a birthday thank-you note my six-year-old son had written on Nov. 13, 1971.

At the bottom of the page I’d scrawled:

Do I assume that you have given up writing to me?

Mum’s response, as I remember it, was to the effect that if she wrote to one member of my family, it was to be assumed that she was thinking of us all. Here’s my response:

Nov. 23, 1971

I’m sorry that you got so uptight about my comment, Mum. However, I think we should clear up some basic misunderstandings about the children. I am delighted that you have written to them, and they are too. They think it is pretty special when an adult relative takes an interest in them. But it is very important to me that the kids be seen as individual people, with interests and responsibilities of their own, and this includes developing communications with other adults outside the immediate family. This, I think, is a reaction to my own childhood, when you tended to take over any attempts we made to establish relationships with other people. Now don’t get upset – I’m just trying to show you how I see myself, and how I see my kids. If you only have time to write to the kids, that’s O.K. I’ll encourage them to answer your letters, but there may be some long gaps. They are not big enough yet to handle a regular correspondence. But I have no intention of taking over the responsibility for them, nor of regarding your letters to them as some sort of gimmick substitute. I am an individual person too, and I haven’t had a letter from you since August.

We made up our differences in the next round of letters. In response to her plaint about the difficulty of being a parent, I wrote:

Dec. 14, 1971

I know what you mean, Mum, about bringing up kids. I sometimes wonder what these two will hold against me when they grow up, and it’s sure to be something I’ve never thought of.