Archive for the ‘art’ Category

The Easter Bunny mystery

How could my husband and I be so mean as to deny our kids the Easter Bunny? I frowned as I reread the letter to my parents stashed in my old black filing cabinet.

12 April 1971

The kids are back at school today after their week of Easter vacation. The weather has been so beautiful and spring-like. This is something I couldn’t really understand until I came to the northern hemisphere—the significance of Easter as a spring festival—the death and rebirth of the god that is an important part of almost every religion there has ever been. Here a big thing at Easter is the Easter Bunny, who is alleged to bring baskets of candy eggs and goodies to kids on Sunday morning. This Tony and I just can’t go along with—somewhat to the kids’ disappointment, I think, though we do buy them a fancy Easter egg, and of course we have the fun and mess of dyeing hard-boiled eggs and hiding them in the garden for an egg hunt. I did allow Simon to share our pet rabbit at school one morning. Bun-Bun was less than enthusiastic about the whole project, but the children were ecstatic.

Part of the reason for our rejection of the Easter Bunny was that Tony and I grew up in New Zealand, where rabbits were despised as pests. Brought by early settlers to a place with no natural predators, their population quickly reached plague proportions, causing major erosion problems. We did have Easter eggs, but given that we celebrated the festival in the Southern Hemisphere autumn, they had no significance other than as a source of sugar and chocolate. Even living in California, we couldn’t see any connection between rabbits and the Christian celebration of the Resurrection. I decided this week to look into the question. I quickly found myself down a fascinating rabbit hole of customs, beliefs, and theories, many of them contradictory.

How the Easter Bunny came to the U.S. seems pretty clear. According to several sources, the creature first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” who brought colored eggs to good children at Easter. As the custom spread across the U.S. the hare somehow transformed itself into the more familiar rabbit and its Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts.

The hare’s (or rabbit’s) connection with Christianity are more complicated. For the first few centuries, the Christian festival coincided with the Jewish Passover, which is when the historical events surrounding Jesus’s death occurred. Though the Christian calendar has since been modified, both festivals are still close to each other in spring. Both are based on a lunar calendar; the date of Easter was defined in 325 CE by the Council of Nicaea as the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. In Anglo-Saxon regions of Northern Europe, the Christian festival seems to have merged with a pre-existing equinox festival honoring Eostre, the goddess of spring, and Christians continued to use the name of the goddess to designate the season. Since hares and rabbits give birth to large litters in early spring, they have long been recognized as symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the vernal equinox.

No, no, no, say some Catholic writers. The Easter Bunny has Christian origins. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that the hare could conceive again while pregnant, thus shortening the time between litters and delivering more offspring during a breeding season. Later Greek writers such as Pliny and Plutarch expounded the notion that hares (and rabbits, by association) were hermaphrodite, and thus could self-impregnate and reproduce as virgins. During the medieval period, hares and rabbits began appearing in illuminated manuscripts and paintings depicting the Virgin Mary, serving as an allegorical illustration of her virginity.

Two pregnancies at once? Intrigued, I veer into another passageway of my research rabbit warren. It turns out that, as the Smithsonian Magazine put it, “Aristotle got it right: the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) can get pregnant while it’s pregnant.” In 2010, scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, Germany, led by Dr. Kathleen Roellig, published the results of their study. Using selective breeding and high-resolution ultrasonography, they showed that a male hare can fertilize a female during late pregnancy. The resulting embryos will develop around four days before delivery of the first pregnancy. To quote from the Smithsonian article: “The embryos don’t have any place to go at that time, however, since the uterus is occupied by the embryos’ older brothers and sisters. So the embryos hang out in the oviduct, rather like when you wait in your car for a parking space to open up. Once the uterus is free, the embryos move in.”

My head is spinning. I think I need chocolate.

A legacy of crocheted lace

A comment in an old letter to my mother catches my eye:

March 1, 1971

I can’t remember anything about that bit of crochet, Mum, but I guess it probably is mine. Now it will sit in my workbox for years!

Do I still have it? I open the Cadbury’s Chocolate box that holds my collection of crochet hooks and sundry balls of crochet thread. On top sits a small piece of lace, obviously the beginnings of an ambitious project. Was it the piece that cluttered Mum’s workbox? Probably.

The art of crochet was honored in my mother’s family, passed on, like all domestic arts, from generation to generation. The most noted expert was my great-grandmother, Sarah Jane Caundle, whom I met a few times when I was a child. She was born in 1864 to Irish immigrants on a New Zealand goldfield. In a reminiscence my mother wrote:

Outside the back door [of Grandma’s house] in the sun was a stool to sit on. Across the yard in a shed that housed the wash house with its copper and wooden tubs with the toilet next to it. Grandma washed the clothes in the old way with a well-stoked fire under the copper to boil the sheets, etc. The tubs for the rinsing and blueing with a hand-turned wringer between them. While visiting as a small girl I was being taught how to crochet. Trying to make my doll a pink woolen petticoat like the ones Grandma made for us. Something would not go right so I called for assistance. There was Grandma coming across the yard at her usual jog-trot wiping the soapsuds off her arms on her apron (Must always wear an apron) to sort out my muddle. The picture is still so clear in my mind.

… As we grew older we were given doilies and crochet-edged linen for our “box.” At each 21st birthday each granddaughter was presented with an afternoon tea cloth with a wide edge of crochet lace.

Before she died in 1951, Great-Grandma Caundle had started making doilies for her great-granddaughters. I missed out, but inherited a piece of her work from my mother. Fascinated by Mum’s stories about her grandmother’s life, I put together a poem:

Great-Grandma’s Doily

Early afternoon, when chores were done,

Great-Grandma put her feet up on the kitchen couch

and gave herself an hour with crochet hook and thread

to figure out the sequence from a photograph—

chain and double loop and treble—

the mathematical progression of the rounds

revealing patterns satisfying in their laciness.

She learned the art at her mother’s knee

in the dirt-floored hut at the Puriri claim.

Her mother learned it from her Mam

back in Ireland before famine memories

and rumors of gold in the far-off colonies

took Bernie Donnelly and his new young wife

adventuring across the world.

There was a dame school at the diggings.

Great-Grandma might have gone some days

but not enough for fluency in letters.

She had sisters and brothers to mind,

manuka-twig brooms to fashion for the floor,

clay to fetch for the hearth’s weekly whitewash of mud.

She entered service as a housemaid at eleven.

Later came marriage and children of her own,

nine of them, then grandchildren to care for.

All this time persisting in her art,

gifting to daughters and grand-daughters

lacy linens for their marriage chests.

I have one doily, handed down, an oval of white linen

edged with a crocheted frill of tulips in a row,

each stitch pulled neat and tight, a testament

to discipline and practice, and the will

to make time for her art.

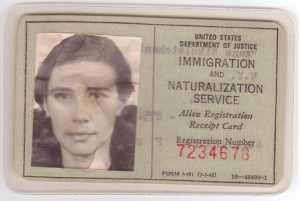

The citizenship decision

In 1972, five years after I emigrated to the US clutching my hard-won Green Card, my official status was Resident Alien. I was required to register at the Post Office every January. If I wanted to leave the country, I had to prove that my income tax payments were up to date. I had to remain “of good moral character” and could be expelled if I had a run-in with the law. And I couldn’t vote.

Meanwhile, opposition to US involvement in Viet Nam was heating up. A turning point for me was the May 1970 killing and wounding of students by members of the National Guard at Kent State University, where students were protesting the secret bombing of Cambodia. As a history major, I already understood why interference in another country’s self-determination was bound to end badly. It was obvious to me as an outsider that the Viet Nam War was a disaster. Yet here in this supposed Land of the Free, it seemed that the authorities were beating up people who said so.

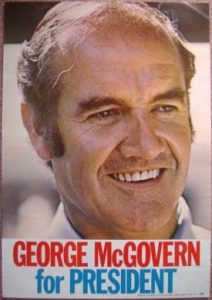

If I couldn’t publicly protest, and I couldn’t vote, at least I could help behind the scenes. I became interested in the anti-war policies of presidential candidate George McGovern, and began to volunteer in his California primary campaign. Here’s how I described my activities in a letter to parents:

June 2, 1972

I have been sticking my neck out in other directions lately too – have become very involved in George McGovern’s presidential campaign. I have put in some time at the campaign headquarters, and then got nailed to organise the local precinct. It is really rather fun, once I got over the initial panic. Support for him is very strong in this area, so I was lucky in the number of people I could con into working for me. Our house is going to be the headquarters for all 30 Cupertino precincts Tuesday (election day), so that should be interesting too. Am meeting all sorts of interesting people, especially the out-of-state students who are travelling around working for him. There are some neat kids amongst them.

McGovern won the nomination, but lost the November election to incumbent Richard Nixon. Meanwhile, I was feeling ambivalent about my own status. After five years in the US, a Resident Alien may commence the application process to become a citizen. Was I ready to do that? Could I turn my back on the land that had nurtured me and my ancestors? Could I pledge allegiance to a country whose foreign incursions I could not support? On the other hand, how badly did I want to share with my neighbors in making decisions about this place we all now called home? For most immigrants, this is a decision that requires careful thought and soul-searching. In the end, my husband and I decided to apply for citizenship. We didn’t know then how many years, frustrations and phone-calls it would take. But that’s another story.

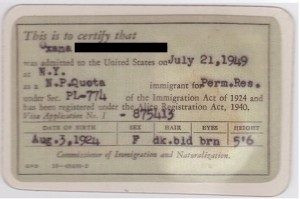

The appeal of the picturesque

I’ve been wondering: what is it about an old house or barn that appeals so much that we describe the scene as “picturesque.” The question came up as I reread a January 1970 letter to my parents describing the purchase of a house in Cupertino, CA. Our new home was a typical early 1960s tract house with scalloped trim and prominent garage. The place was certainly not picturesque, but it was within our price range. I wrote:

It’s a very nice little house – 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, big sitting room with dining area at one end, small family room opening to a neat little kitchen, 2-car garage with laundry facilities in it. Very attractive inside, though not very prepossessing from the outside. However, this is just a matter of landscaping – other houses in the street are just lovely, but the garden of this one is just bare grass.

Looking back on that time, what comes most vividly to mind is another house I saw while house-hunting, a charming old farmhouse dating from the time when the Santa Clara Valley was so full of orchards it was called “The Valley of Heart’s Delight.” As I walked through with the realtor, I paused in what must have been a utility porch and mud room. The unfinished walls of the room were black with mold. The realtor shrugged when I pointed it out. The price was right, but I chose not to make an offer.

There’s a significant difference, of course, between the picturesque, which has been defined as that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture and a habitable structure for humans. But what is it in the human psyche that is drawn to the antique? Rummaging around on the web, I found quotes such as:

(esp. of a place) attractive in appearance, especially in an old-fashioned way

A picturesque place is attractive and interesting, and has no ugly modern buildings.

My friend Sandy Peters says it well. Commenting on a Portola Art Gallery exhibition of her husband Jerry Peters’ paintings of old battered trucks in rural settings, she wrote: They demonstrate how the beauty of nature blends seamlessly with the wisdom of age.

However, with age comes death. When we first moved to Mendocino seventeen years ago, a cabin stood among the trees along Highway 128, not far north of Yorkville. Its bare board were gray with age, the sway-backed roof shingles covered with moss. Over the years, the roof has slowly caved in, until now the cabin is a jumbled pile of boards. At first it was picturesque. Now when I drive by, I am sad.

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

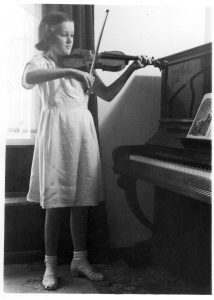

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.

A tale of a sparrow

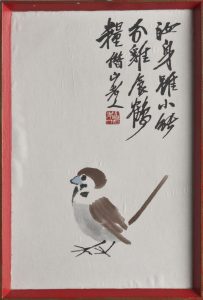

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

14 April 1969

A friend of Tony’s from Memorex came to dinner. A Korean boy … He is really charming, and we had a pleasant evening. One interesting thing that came out of it – Yun also reads and writes Mandarin Chinese, so was able to translate the inscription on our sparrow picture for us. Do you remember our sparrow? It is a little brush drawing that Tony picked up in a junk shop in Hawera when he was a student, shortly before reading in a magazine a story about a famous Chinese artist who was objecting to a government campaign to kill off the sparrows to improve the wheat production. He made these little posters, inscribed with sentimental stories about the sparrow. And this, as far as we can tell, is what we have got.

With the help of the Internet, I’ve been piecing together my fragments of knowledge about this period in Chinese history. What I discovered is a familiar story about well-intentioned interference with nature leading to ecological disaster.

In the First Five-Year Plan of the newly-founded People’s Republic of China, families were each given their own plot of land. In the Second Five Year Plan, begun in 1958, a new agriculture system was announced. Family farms were grouped into collective farms, making each village a single production entity in which everyone would have an equal share. Food would be provided in a communal kitchen.

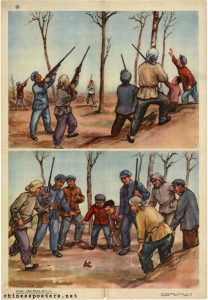

In theory, a collective farm where resources were centrally controlled should be more efficient and yield higher productivity. In practice, agricultural production figures fell. Food shortages were exacerbated by flood and drought. Believing that getting rid of sparrows, who ate grain, would improve production, Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Four Pests Campaign, which encouraged citizens to kill them, along with three other pests: rats, flies, and mosquitoes. Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks were killed. Many sparrows died from exhaustion; citizens would bang pots and pans so that sparrows would not have the chance to rest on tree branches and would fall dead from the sky. Citizens also shot the birds down from the sky. These mass attacks pushed the sparrow population to near extinction.

In hindsight, the result was inevitable. Too late, Chinese leaders realized that sparrows didn’t only eat grain seeds. They also ate insects. With no birds to control them, insect populations boomed. Locusts, in particular, swarmed over the country, eating everything they could find, including crops intended for human food. People, on the other hand, quickly ran out of things to eat, and tens of millions starved.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

The woman on the moor

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The year was 1966. Knowing it might be our last year in England, our family (husband, two infant boys and me) took a summer trip through England and into Scotland, staying mostly in private homes that offered bed and breakfast. A farm in the Peak District of Derbyshire. Across the Yorkshire Dales to Huddersfield and Keithley, from whence my paternal grandfather had emigrated as a young man to New Zealand. Up to a gray stone village on the moors to take tea with a sweet great-aunt who had married and stayed behind when her siblings left, and whose knowledge of the whole New Zealand branch of the family put me to shame. The Lake District, lowering with storm clouds and redolent with Wordsworthian cadences. A stone circle near Keswick. Hadrian’s Wall, a loch in Scotland. Yellowing pictures now fill a photograph album.

The little roadside shop was somewhere in the northern hills of England, on our way home. A gray, damp day, a gray, bleak building. Nothing much else around. We all needed a break from driving, so we stopped. Quickly bored with the arts & crafts contents of the shop, our toddler and the baby drifted outside with their father. I lingered, drawn to the young woman attendant, who sat at a table threading beads into a necklace. A knitted shawl around her shoulders, long mousy hair falling in a braid down her back. We chatted. She had left an unhappy relationship and was determined to survive on her own.

She had the confidence I lacked. Brought up in a conservative culture and married young, I was struggling with a sense of powerlessness in my traditional wife-and-mother role. There were times I felt trapped, and thought of escaping with the children back to New Zealand. But this would have felt like defeat. Besides, it was impractical. I had no money to pay for fare, no clue about how I would manage on my own once I got home.

My encounter with the woman on the moor was brief. I never learned her name. But the amethyst ring symbolizes an unspoken pact between us. What I gave her was good wishes and payment for her work. What she gave me was confidence that I too could find my inner strength. This is what I remember when I wear it.

Furnishing a house, 1960s style

A magazine clipping tumbles from a November 1964 letter from England to my parents. It’s the picture of a dinner service I won in a menu-planning competition. Looking at the geometric pattern on the dishes, I realize that the way we furnished the row house we bought that year has many elements of what is now recognized as a distinctive 1960s aesthetic: bold shapes and strong colors.

Having limited funds, Tony and I refurbished or made many pieces of furniture. The dining table he made was a heavy white plastic-veneered slab with straight, varnished wood legs. He built, and I upholstered, a sofa and side chairs with squared-off, simple lines, a copy of a set we particularly liked, but whose price was prohibitive. I made all the curtains from fabric purchased at Heal’s of London, the store that carried the trendiest of household furnishings. I wrote:

8 August 1964

The sitting room curtains are quite magnificent – deep orange flame colour, with a pattern called “Armada,” the formalised ships’ hulls giving the impression of a dark horizontal stripe.

A shag (another 1960s design element) area rug that matched the curtain’s colors helped warm up the coldness of the room. After battling the developer over the house’s color scheme, we had compromised on gray vinyl tile floor and plain white walls. In the kitchen and dining area, we covered the white with a geometric wallpaper. A photograph reveals more geometrics: the gray and white kitchen curtains, the cups and saucers on the counter.

We still have one platter from that dinner service I won. A few other items, mainly metal, have survived the years. A pewter jug purchased on board ship during our emigration from New Zealand to England still sits on our kitchen windowsill. To the right of the dinner service picture, behind a porcupine of cheese chunks on skewers, are familiar objects: salt and pepper shakers just like the ones we still use every day. I guess we, like these furnishings, can all be labeled “vintage.”

A long, slow saga of first-time house buyers

In 1964 my husband Tony came into an inheritance, enough to put a down-payment on a small row house in a village on the outskirts of London. From first placing a ?50 holding payment on a partially-built structure to actually moving in took seven months. Today, with the purchase, remodeling and/or building of four subsequent houses behind me, I read my letters to parents from that period with wry sympathy, thinking how universal is the impatience of a young couple buying their first house.

The first letter in the series has a page or more of excited detail.

11 May 1964

… though still with the nagging doubt that it is all too perfect, that something is sure to go wrong. Points in favor: a brand new house within our price range (rare), architect-designed with imagination (also rare), less than a mile from Tony’s job, practically in the country with a charming view over open fields to woodland, closer to London (20 minutes by fast train to Waterloo) and won’t be finished for three months by which time we should have the means to pay for it…. Small, of course, but with ingenious use of space and attractive layout …

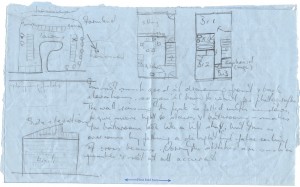

When I was growing up, my mother filled binder after binder with house design ideas and plans. We (my parents, three children, and succession of boarders – aunts, uncles, and family friends, often two at a time) lived in a rental Craftsman bungalow built about 1910: two bedrooms and a sleeping porch accessible only through the parents’ bedroom and through a laundry room in which a toilet was installed late in our tenure. (Before that, we used the outhouse back in the yard.) Mum eventually built her dream house when I was about thirteen. In the meantime, I learned a lot about building design and became very familiar with architectural drawing and its symbols. I drew her a sketch:

After a month of marking time, and a thickening correspondence file, a tirade about a building society (English equivalent of a mortgage company) to whom we had applied:

8 June 1964

… the building society wouldn’t consider our house for a mortgage because it was too contemporary in design – they stick doggedly to the deadly dull conventional things. We saw one the other day, part of an estate quite near here – good solid brick, appallingly bad planning, and claustrophobically tiny windows. Mortgages no bother.

A month later, good news on the offer of a loan from another building society. However, letters for the next several weeks report a battle with the developer:

30 July 1964

… One of the hazards of a speculative development – they are very reluctant to depart from the standard model, which in this case is decidedly murky – masses of dark grays, black, browns & blues. I’m getting a bit fed-up – sick of looking at samples & doing sums – I want some action round the place.

8 August 1964

… ran into trouble over the alterations we wanted to the colour scheme – we were met with a blunt ‘take-it-or-leave-it.’ However, eventually Tony rang up & told them they were a lot of bloody-minded so & so’s, & managed to get the most important concession – the colour of the tiles on the floor. The rest of the detailing we shall probably have to rip out & replace as we can afford it. Infuriating, but the housing situation being what it is, we daren’t tell them to go to hell.

Inevitably, construction delays kept postponing the finish date for the house:

26 Sept. 1964

We went up to London on Tuesday to sign the lease & mortgage documents for the house. Exciting, but still somewhat unreal. I am ceasing to believe in the existence of the house, and find it rather unsettling to go over every other weekend or so & find they have done a tiny bit. Still no idea when we can shift in – it will probably be weeks yet.

8 December 1964

It is still hard to believe that we have actually moved in. Up to 9:15 on Friday morning, with the carrier already piling boxes into the van, we still didn’t know if we could – it all depended on the cheque from the building society being in our solicitor’s post. A strange, unreal situation to live through. However, talking to some of the other people who have moved in, they seem to have had much more trouble than us, so we must be thankful.

Anyway, in all the chaos of cancellations, postponements, etc., it was too much trouble to cancel our housewarming party, so we held it as planned on Saturday night. The earliest arrivals were detailed off to put up curtain rails, shift packing cases from the middle to the sides of rooms, etc. Quite a successful party, I think. About a dozen people (& kids) stayed overnight, dossing down wherever for what was left of the night – we got to bed about 4 am, & a few more people dropped in for brunch the next morning. Needless to say by today we are both pretty worn out, but the house is more or less habitable. Strange what an effort, both physical & mental, to make a shell filled with boxes into a habitable room.