Archive for the ‘Movies’ Category

Technological breakthrough brings excitement

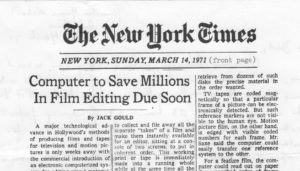

On March 29, 1971 I scrawled a letter to my parents on the back of a copied newspaper clipping. In it I wrote:

We thought you might be interested in this cutting from the New York Times. It was also reproduced in the local paper, as well as the major papers in Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles, and the phone hasn’t stopped ringing at CMX [the company where my husband Tony worked] ever since. They have been demonstrating to all the major movie & TV producers & advertising agencies – a fascinating assortment of characters around the place, Tony says. Tony is going to Denver, Colorado for a magnetics conference the week after Easter. I think he is feeling quite amused about confronting the magnetics “Establishment” who were convinced that what he did (using magnetic computer disks to record video pictures) was technically impossible.

The article, by Jack Gould, the New York Times’s television and radio critic and reporter, goes into more detail. “Computer to Save Millions in Film Editing Due Soon” is its title. Calling it “a major technological advance in Hollywood’s methods of producing films and tapes for television and motion pictures,” he wrote:

The article, by Jack Gould, the New York Times’s television and radio critic and reporter, goes into more detail. “Computer to Save Millions in Film Editing Due Soon” is its title. Calling it “a major technological advance in Hollywood’s methods of producing films and tapes for television and motion pictures,” he wrote:

“In layman’s terms, the heart of the CMX system is its ability to collect and file away all the separate “takes” of a film and make them instantly available for an editor, sitting at a console of two screens, to put in coherent order. This working print or tape is immediately made into a running whole while at the same time all the trims and cuts are preserved for later consideration.

“Operation of the system borders on the eerie. The console operator can order up whatever he wishes to see. He presses no buttons or pulls any switches. Rather, he uses a pencil light that directs the system to offer a choice of “menus,” i.e., whether he wants the system to record, play back or edit.

“If the director wants to see Scene 1 of Act 2, he presses his pencil light, actually a photoelectric cell, against those words on the face of the screen. Instantly there is a still picture denoting that the sequence is ready for study. The light is then pressed against the word “run” and the scene starts.

“With the same pencil light the operator can order the system to stop. He can thereupon order a new starting point and new ending. Thereafter he can review the edited scenes and, if he wishes, compare them with the original.”

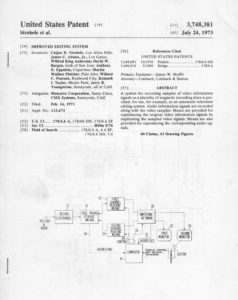

CMX Systems was a joint venture between the Columbia Broadcasting System television network and Memorex Corp., the company that had brought us to California in 1967. According to Wikipedia, the company’s name stood for CBS, Memorex, and eXperimental. Tony and his colleagues shared a patent for their work, as well as the satisfaction of having contributed to a breakthrough in technology. The company was sold in 1974, and Tony returned to Memorex, where he continued to work on magnetic recording technologies.

Movies for the intellectual set

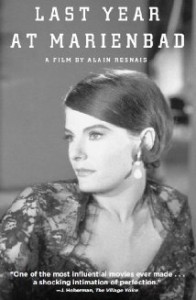

“I’ve seen Last Year at Marienbad seventeen times already,” our college friend Bill told us as he showed us around London on our arrival in 1962. “I still haven’t figured out what really happened. I’ll have to go again this weekend.” This enigmatic movie, directed by Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet, is considered a masterpiece of the French New Wave. The movie website rottentomatoes.com comments: “Elegantly enigmatic and dreamlike, this work of essential cinema features exquisite cinematography and an exploration of narrative still revisited by filmmakers today.”

For my husband Tony and me, it exemplified the rich cultural life we discovered in London. In New Zealand, where we grew up, to be an intellectual was to live as a small coterie on the outskirts of society, viewed with suspicion by the mainstream. To be an intellectual in London was to be part of a big vibrant conversation, fueled by articulate reviews of movies, books, art exhibitions, plays and dance performances in the Sunday Times and other papers. In between job hunting and flat hunting, we took the opportunity to participate as much as possible.

Reading again a letter to parents dated April 18, 1962, not long after we arrived, I note a distancing of myself from this new world of ideas, possibly a Kiwi reluctance to admit my eagerness to be part of it. I wrote:

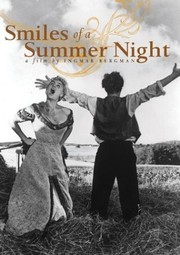

London is chockfull of fascinating characters – you meet them everywhere – on the street, in the Underground. All sorts and shapes and sizes. We met the intellectual set last night – went up to a cinema at Hampstead Village – on the edge of the Heath – which is obviously run by and for the intellectual crowd – hard red and black in the décor, and the finishing touch a handsome beaten copper plaque for the exit sign. They have been showing a series of all Ingmar Bergman, the modern Swedish director’s films. The place was packed out with long hair and beards and intense faces. Almost as interesting to watch as the film. It was a very delicate and charming piece called “Smiles of a Summer Night.” We also saw another interesting film the other night – Alain Resnais’s “Last Year at Marienbad” – highly psychological (and apparently the intellectuals’ current talking-point!) The story (if you can call it that) is that a woman meets a man at a spa who tries to convince her that they were intimate there the previous year, but she thinks she has never seen him before. Scope for highly intriguing playing around with time and facts, with emotional distortions.

London is chockfull of fascinating characters – you meet them everywhere – on the street, in the Underground. All sorts and shapes and sizes. We met the intellectual set last night – went up to a cinema at Hampstead Village – on the edge of the Heath – which is obviously run by and for the intellectual crowd – hard red and black in the décor, and the finishing touch a handsome beaten copper plaque for the exit sign. They have been showing a series of all Ingmar Bergman, the modern Swedish director’s films. The place was packed out with long hair and beards and intense faces. Almost as interesting to watch as the film. It was a very delicate and charming piece called “Smiles of a Summer Night.” We also saw another interesting film the other night – Alain Resnais’s “Last Year at Marienbad” – highly psychological (and apparently the intellectuals’ current talking-point!) The story (if you can call it that) is that a woman meets a man at a spa who tries to convince her that they were intimate there the previous year, but she thinks she has never seen him before. Scope for highly intriguing playing around with time and facts, with emotional distortions.

Over the next few years, we saw almost all of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, which I still love, along with many by the French New Wave directors. I learned to accept that I too was an intellectual.

Over the next few years, we saw almost all of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, which I still love, along with many by the French New Wave directors. I learned to accept that I too was an intellectual.

Inside a 1960s newspaper office

In graduate seminar at the University of Canterbury, Professor Neville Phillips fixed me with a stern eye as he returned my latest effort. “You are getting through your history papers, Miss Dinsdale, on your writing style, not on your knowledge of history.” I flinched, and worried. Graduation was coming up, and I planned to apply for a job on The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. Within the next week or two I needed to ask him for a letter of reference. Not only was Prof. Phillips head of the history department, he was a former newspaperman himself, and still had deep connections at The Press.

I needn’t have worried. Not only did he write me a nice reference, he also penned a personal note to the paper’s editor, Arthur Rolleston (Rollie) Cant, that opened the door to my dream job.

Press Building, Cathedral Square, Christchurch, NZ. Photo by Michael Whitehead from

http://www.nzine.co.nz/features/150years_the_press.html

I had known since childhood that writing was what I wanted to do. Movies about newspapers such as While the City Sleeps (1958), Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) and Ace in the Hole (1951) filled me with fantasies about the drama and excitement of the reporter’s life. Here was my chance to prove myself.

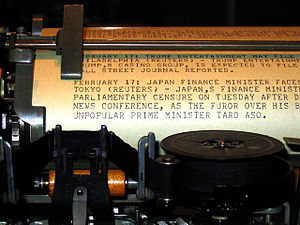

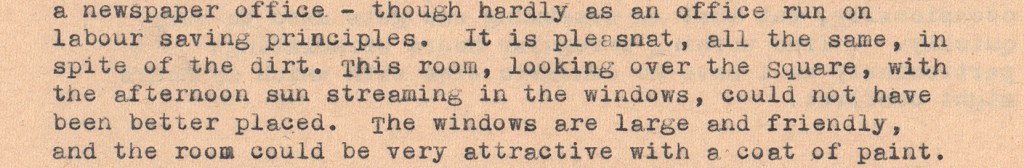

I loved working at The Press. A great Gothic pile on Cathedral Square, in the heart of Christchurch, the Press Building was a newspaper office out of one of those Hollywood movies: a cavernous newsroom that smelled of newsprint and dust, where telephones jangled, the chief reporter barked commands and the urgent clatter of the Teletype machine signaled a breaking story somewhere in the world.

Picture of Merganthaler linotype machines in a compositing room from the archives of the Nieman Foundation http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/

Sometimes I would be sent on an errand out back to the compositing room, a shadowy cave where enormous Mergenthaler Linotype machines made a deafening clatter. Deeper into the heart of the building, the throb and rumble of the great press itself, and the bustle of loading trucks in the small hours of the morning for long distance runs. When The Press celebrated its 100th anniversary in May 1961, its circulation was 62,000, with subscribers throughout the South Island.

It felt glamorous to work late into the evening, rushing back from meetings to meet the deadline for next morning’s paper. I shared dreams with the other young reporters, all of us with a few scratched notes tucked away for what each of us was sure would be the Great New Zealand Novel. We all had the sense of being part of an old tradition.

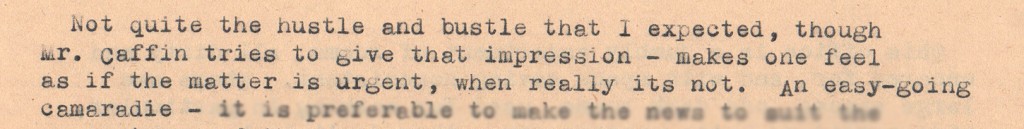

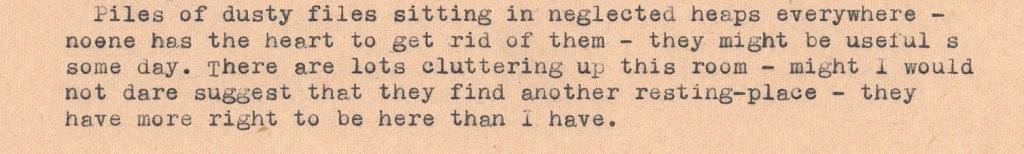

Among my notes I found this description of the office, written in 1960. Christchurch at that time was a sleepy provincial city of 193,000 people, and exciting news stories didn’t happen all that often.

I described the office as a jumbly assortment of rooms, all dirty and uncared for, and with space saving nonexistent.

I particularly appreciated my desk in the women’s department, by a window where I could gaze out across Cathedral Square. I’ve written about this view in an earlier post.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Cooking for 120 in a remote fishing camp

The Curious Cove camp, now known as Kiwi Ranch. It looks much the same as when I worked there in the late 1950s.

If you take the ferry from Wellington, New Zealand across Cook Strait and through the Marlborough Sounds to Picton, at the northern end of South Island, you will sail past the entrance to Curious Cove. At the tip of that narrow inlet is the tiny fishing camp where I worked through all my college vacations. Reachable only by boat, Curious Cove was a magical little world. The job, passed down through word of mouth by University of Canterbury women students, was perfect for this impoverished student, with board and lodging provided, nothing but a tiny tuck shop to spend money in, and a nice paycheck at the end of the season. I started off as a kitchen hand and was later promoted to second cook.

The guests, about 120 at a time, would come in for a couple of weeks. We would feed them a full breakfast, then scramble to pack lunch sandwiches for those going out fishing. Those who stayed behind got freshly baked scones with their mid-morning tea, and a salad and cold cuts lunch. By late afternoon, when the launch, “Rongo” hove into view with Charlie the skipper at the helm, the kitchen crew was already at work on the evening meal. It would be plain, traditional New Zealand fare: a roast with gravy and several vegetables, plus a dessert such as apple shortcake with custard.

Here’s a classic New Zealand apple shortcake recipe.

Almost everything was made from scratch. The 1950 movie Cheaper by the Dozen, the story of time and motion study experts Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and their twelve children, was as big a hit in New Zealand as it was in the U.S. Following the Gilbreths’ methods, the Curious Cove kitchen crew, being university students, amused ourselves by figuring out more efficient ways to do things.

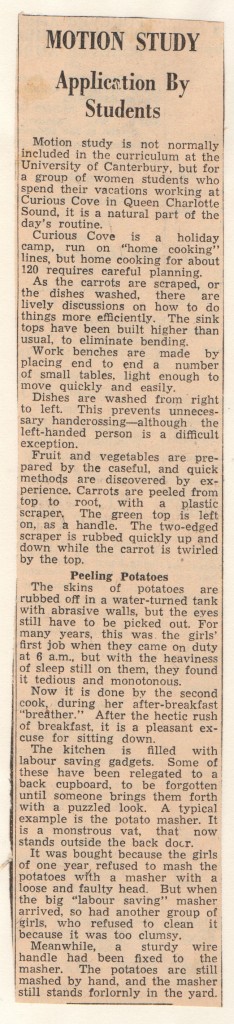

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The King’s Speech

This weekend we saw the movie, “The King’s Speech,” that has been nominated for a slew of Oscars. Enjoyed it very much. Although the history was prettified (the British administration’s attitude toward Hitler was more ambivalent than shown), this did not detract from a moving story. I was only a toddler when King George VI made the famous war speech that climaxes the story, but I must have heard excerpts, the sound of the words was so familiar. My earliest memories are of the hush in our New Zealand home when the BBC news came on. First the stately chimes of Big Ben. Then the announcer’s voice, orotund and crackly over the long-distance airwaves: “This is London calling. Here is the news, read by …” Pictures in the newspapers of King George and Queen Elizabeth inspecting bomb damage in London and comforting the survivors. They were our king and queen, and we loved them too.

The story of “The King’s Speech” is of the future king’s terrible stammer, and of his relationship with the Australian speech therapist Lionel Logue, a World War I veteran who stayed in England after that war ended to help soldiers whose powers of speech were traumatized by their experience.

One scene hit me hard. Logue, an aspiring actor and Shakespeare enthusiast, is auditioning with a local dramatic society. Their snobbish rejection, based on his Australian accent, thrust me painfully back to the years I lived in England during the 1960s. The English class structure was rigid. My accent pigeonholed me as a colonial, a box from which I could not escape.

Whether fictional or not, the king’s loyalty to Logue the Australian, in the face of his advisors’ disapproval of the fellow’s humble origins and lack of proper credentials, endeared me further to His Majesty.