Archive for the ‘poetry’ Category

My new poetry collection

I am excited to announce that Finishing Line Press is now taking pre-publication orders for my new poetry collection, Earthward. It can be ordered now and will be printed and shipped in October. You can order online from the publisher at https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

The cost is $14 plus $2.99 shipping. The publisher bases the size of the print run on how many pre-publication orders they receive, so I hope you’ll consider adding to my tally. Please feel free to suggest this book to others you think might be interested too.

The poems in Earthward explore the cyclical patterns of life. Here is a sample poem:

Osprey With Fish

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

I’ve been honored to receive reviews from poets I admire:

With a naturalist’s eye for the precise and sensuous image and a writer’s care for the precise and sensuous word, Maureen Eppstein plants our human griefs into this book, roots them, and invites them to quicken into new life.

—Jane Hirshfield, author of Come, Thief

What captivates me about Earthward is the way Maureen Eppstein transforms ordinary landscapes into miraculous acts of affirmation. Turning compost becomes an opportunity to ponder death and resurrection, braiding garlic reminds us of the “pleasure taken in braiding the hair of the beloved”. This is poetry of quiet lyrical depth, that reconnects us with land and spirit. Earthward invites us to stand deeply rooted in each moment, “in awe and wild surmise at all this human brain can not yet comprehend.”

—Devreaux Baker, author of Red Willow People

In Earthward, Maureen Eppstein unites what would break us with what will bring us back to life. The wild ones, like us, must eat, and so kill. Lost sisters are mourned by proxy. Some things we love are transplanted and transplanted again, surviving and sometimes thriving. The tenacity Eppstein describes is the foundation of our lives. There are those who say that to write about the extraordinary one must look lovingly at the ordinary. Eppstein knows where, and how, to look.

—Camille T. Dungy, author of Smith Blue

Here’s a brief bio:

Maureen Eppstein is the author of two previous poetry collection: Rogue Wave at Glass Beach (2009) and Quickening (2007), both published by March Street Press. Quickening was also first runner-up in the 2007 Finishing Line Press/ New Women’s Voices competition. She has been a finalist in several other book contests. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including Poecology, Calyx, Basalt, Written River, Sand Hill Review, and Aesthetica 2014, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Crossing the boundary between the arts and the sciences, her poems have been included in a textbook on computer graphics and geometric modeling and used in a university-level geology course.

A Little House for Poetry

The idea came from an article in the Sept.-Oct. 2013 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine about a project to erect small installations, called poetry boxes, in public places. Their purpose, according to the artist, is to “connect people to landscape by combining poetry, visual art, and nature observation.”

The idea came from an article in the Sept.-Oct. 2013 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine about a project to erect small installations, called poetry boxes, in public places. Their purpose, according to the artist, is to “connect people to landscape by combining poetry, visual art, and nature observation.”

I decided to design a poetry box for myself. A simple little house, with just a touch of decoration: a carved spiral to symbolize the continuity of life, and a line of chevrons to signify water. I have no skill at woodwork, but my husband Tony does, and he readily agreed to take my plan and build it.

Here it is, mounted on the 6” x 6” gatepost of my fenced vegetable garden. The laminated text is thumbtacked to the back of the box, so that I can change it whenever I want to. For its debut, I placed an empty seed packet on the floor of the house and pinned up a few lines from my poem “Winter Greens,” which is published in my collection Rogue Wave at Glass Beach.

This is the gesture of hope:

to remember the taste of fresh-cut salad greens

and act on it.

This is the act of reconciliation:

muscle rhythm of shovel and wheelbarrow,

load upon load to fill the planting box.

This is the sound of faith:

a rake tamping down soil over new plantings—

snap peas, bok choi, lettuces—

tines on the diagonal, first one direction

then crisscrossed down the line.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I plan to read this poem at tonight’s Solstice event at Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino. Obviously it was written in a year other than 2013. We’ve had no rain all month, and none in the extended forecast, so face the likelihood of a drought year. I think of this piece as a kind of prayer.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I honor the rain that plummets from a leaden sky

on this day when the dying sun returns to life.

I honor the wet earth where fungi lift

the smells and secrets of their darkness

into forms potent with wildness

and fallen leaves grow slimy with decay.

I honor the sudden green suffusing

the face of the sun-scorched hill,

like the blush of knowledge in a woman’s face

after her first coupling.

I honor the flame of candle and hearth

that draws to itself the breaths

of all whose lives have sometime crossed,

mingles and transmutes them into warmth

and sends them out into the rain

where they caress the tender growing tips of trees.

Texts

Searoad, a story collection by Ursula K. LeGuin, has a permanent place on my bedside table. It’s there because every now and then I need to reread a certain story. A very short story, less than three pages, it is titled “Texts,” and tells of an older woman who, bombarded by messages and calls to action, retreats to the coastal Oregon village of Klatsand for a month-long winter break. As she walks on the deserted beach, she notices that the waves have left messages in the lines of foam, messages she can almost decipher. The laciness of the foam leads her to speculate that crochet work and lace might also be legible. In a handmade lace collar she reads a message that seems directed to her: “my soul must go, my soul must go … sister, sister, light the light.” There the story ends, with the woman not knowing “what she was to do, or how she was to do it.”

I think of this oddly moving little story every time I walk on Ten Mile Beach, as I did last Sunday. The receding waves left undulating lines of bubbles, iridescent in the hazy sunlight, that popped to form patterns of foam. Scattered across the beach were strands of bull kelp, dried into coils and loops that lay like a cursive script on the sand.

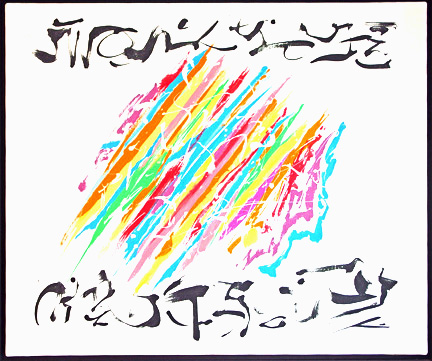

Yesterday, when the wind was brisk and the sea streaked with white caps, I remembered an interview I did for the Mendocino Art Center magazine. It was part of a series I wrote on artists who helped found the art center in the 1960s. By the time I met Jim Bertram in the early 2000s, he was senile and nonverbal, so I had to rely on material in the art center archives for information about his background and artistic vision. Nevertheless, Jim and I spent a wonderful afternoon together. I think a poem I wrote at the time sums it up:

MESSAGES

For JB

“Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.”

– Jim Bertram

These bright spring days, when the wind

scribbles its white calligraphy

on a wash of aquamarine,

I think of the artist in his studio

upstairs of a weathered storefront

overlooking Mendocino Bay.

Sheet after curling sheet he showed me, canvas

after canvas, covered with calligraphic forms

that could have been words, but were not.

In our shared silence I understood his drift:

how sometimes what matters most is inarticulate:

like the line of spray from a lifting wave,

the hand of an old man painting messages of love.

On my way downstairs from Jim’s studio, I fell in love with one of his paintings, which now has a place of honor in my house. I smile when I read its message.

Rain

This last month of our annual dry season, as grasses turn dusty brown and the trees droop, a phrase from a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem has been running through my head: “Send my roots rain.” This week the first good downpour broke the drought. I found and reread Hopkins’s poem, and recognized in it the cry of every writer who, like myself, goes through a dry spell and pleads for the rain of words and ideas.

Hopkins’s sonnet begins as a Job-like argument with God. He is angry that “sinners’ ways prosper” while he, a Jesuit priest who spends his life “upon thy cause,” sees his every endeavor end in disappointment.

The tone shifts in the second part of the sonnet. Hopkins points out the exuberant natural world:

See, banks and brakes

Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build …

He compares these images with his own struggles. He does not build, he says,

but strain,

Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Hopkins sold himself short, of course. His poems continue to waken in the minds of later generations. But that sense of self-doubt is one all writers share. Whatever our spiritual beliefs, we can join in the prayer of Hopkins’s closing line:

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

You can read this sonnet, and link to other poems by Hopkins, at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173669

Wave/Rock

I’m jealous of Scottish visual poet Ian Hamilton Finlay.

Last Sunday morning I walked on the cliffs at Chapman Point, just south of Mendocino. Tony, who does the graphics for Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, was taking photographs that might become next year’s program cover or a display ad in Poets & Writers magazine . I contemplated spume lifting from waves as they rolled in steady rhythm against the rocks, and thought about words I might use to convey the sense of transience that pervades this dramatic boundary between earth and sea.

Back home, I started making a list: undercut, backwash, swirl, surge, strata, submerge, carve, crevice, recede, collapse, uplift, unrest, rockfall, bull kelp, blueness, sheer … A few lines started to appear:

In the curve of the undercut

at the cliff’s base

the shape of wave

I decided to let the lines sit for a while and turned to another project. My friend Mary Marcia Casoly had recently sent a link to an anthology, Shadows of the Future: An Otherstream Anthology containing two of her poems. “Vispo,” she called them, visual poetry. Not a form I knew much about, so I Googled it and found a number of sites that had definitions and examples. Visual poetry, I learned, is “poetry that cannot suffer any translation into alternative visual or typographic form without sacrificing some of its meaning and integrity… The ‘quality of presence’ we get from the work depends on visual means, such as typefaces, format, spatial distribution on the page, or the physical form of the book or book object.” (Johanna Drucker)

I opened an example at random. Immediately my entire afternoon at my desk was washed out to sea. Before me was Ian Hamilton Finlay’s “Wave/Rock” from Aspen #7. Just two words repeated: the brown rockrockrock stacked on top of each other so that the near-vertical strata are visible; the blue wave words spread and broken as they crash against the rocks.

Anniversary of a Departure

Fifty years ago today, my husband Tony and I said farewell to family on the quay in Wellington, New Zealand, and walked up the gangplank of the ocean liner Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt, drawn by that migratory urge young New Zealanders have to explore the other side of the world. This poem says a little about how it felt.

LEAVING NEW ZEALAND

I am Katherine Mansfield come again

on that slow ship out of Wellington.

Taste of bile in my mouth, I endure

the airless heat of the lower decks

rank with galley smells

and the deep-throated thump of engines.

The ice-slick of my daughter’s death

stumbling my speech,

I sit with parties playing Scrabble on the deck

where Indonesian stewards in white jackets

rattle tea-trolleys.

Evenings, I watch for that streak of light

as sun plunges into viscous sea.

Then sudden dark.

Familiar stars of my Antipodes

recede southward.

In their place, carved mahogany panels

that fill the walls of staterooms and stairways:

solemn eyes of strange beasts

peer from behind carved vines,

birds in extravagant plumage

perch on the edge of my dreams.

A Lifetime of Friendship

“I have not written these poems, nor even read them; this is a spoken book,” declares my friend Diana Neutze on the back cover of her latest collection, AGAINST ALL ODDS. The title refers not just to her illness—she has battled Multiple Sclerosis for well over forty years—but to the difficulties inherent in transforming poems from her mind to the printed page. As MS closed down her body, she progressed from longhand, to one finger on the computer, to voice recognition. “But now I dictate to Gabrielle, my editing carer. Even the editing has been done by voice, backwards and forwards in the air.”

I was privileged to receive a copy of this handsome limited edition. Written over the past three years, the poems chronicle the poet’s recognition that her death is imminent and her determination to live each remaining day in the beauty of the moment. The poems are rich with images such as: …a tangle of branches/ peremptory against a crystal sky. She asks:

If I died tomorrow, what would

happen to the poems in my head?

Christchurch, New Zealand, where Diana lives, has suffered a series of devastating earthquakes and aftershocks that figure in many of the poems. In “Elsewhere” she writes:

…the earth where I thought

to lay my final bones

is writhing like a wounded snake.

The earthquake draws her mind outward to share a communal grief:

I mourn for the lost, the mained, the dead.

I mourn for our grieving city.

The experience of working with composer Anthony Ritchie on a song sycle of her poems draws her to a new awareness of the importance of people in her life. The final poem in the book reworks “Goodbye,” the final poem in the song cycle. Keeping the opening lines: If this day were to be/ my last …, she traces the trajectory of her preparations for death, from spiritual and inward-looking to a recognition of a fear in which …I relegated/ my friends to the outer suburbs. The poem ends:

If tonight were to be my very last,

I would be desolate

at leaving behind

a lifetime of friends.

I have been friends with Diana since our freshman year at the University of Canterbury, fifty-four years ago, where we met in English Literature class. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate parents of small children in London. Over the years and across the globe we have stayed in touch, supporting each other as best we could in times of grief, commenting on each other’s poems, occasionally visiting. I honor this lifetime of friendship as I read AGAINST ALL ODDS.

Words and Music from an Inner Garden

For more than forty years, my friend Diana Neutze has endured the relentless thefts of multiple sclerosis and grief for a son lost too young. Throughout that time, she has continued to write powerful and moving poems. Recently, her body closing down, she commissioned the New Zealand composer Anthony Ritchie to set some of her poems to music. The cycle of seven songs, “Thoughts from an Inner Garden” premiered April 2011 in a performance at Diana’s house in Christchurch, New Zealand. Diana recently sent me a CD of that performance. I’ve been playing it over and over, overwhelmed by the beauty and intensity of the work.

From Diana Neutze’s published collections, A ROUTINE DAY and UNWINDING THE LABYRINTH, Ritchie selected poems that express the poignancy of the poet’s sense of connection with the tangled garden that surrounds her house, a garden that has become her world. Transcending the nightmare of her chronic illness, she finds meaning in the details of the natural world: the play of light and shadow, the song of a bird.

The cycle opens in a minor key, an ancient, timeless sound that describes a day of wet greyness without wind when the garden is holding its breath. In “Bridal,” the second song, the poet, showered by autumn gold, imagines the roses and smoke bush as witnesses to a marriage between herself and the garden. The mood changes in “Chronic,” where Ritchie’s urgent rhythm reflects the tick-tocking of illness/ relentlessly. “And the Birds Sing” is a meditation on the cycles of life and death. “A Scent of Water” offers a fragile hope in the face of grief: a frosting of growth/ a shivering of buds in the morning light. The rhythms of an old folk dance come to mind in “Meaning.” A moment in late afternoon, a blackbird singing in a weeping elm, and the day is flooded with meaning. The cycle closes with “Goodbye.” The poet recalls the garden images she will die loving. The theme of a Bach partita enters the music as she describes its architectural splendour … arch after musical arch soaring upwards.

Season Words

A small group meets at my house once a month to talk about poetry. We take turns to choose the topic and lead the discussion. Yesterday’s topic was haiku, a classic Japanese form. We considered the arguments about Robert Hass’s poems in recent issues of Poetry, and agreed that the small fragments quoted have to be considered in the context of the whole poem. They should not be thought of as haiku. We read translations, by Hass, Jane Hirshfield and others, of the great Japanese masters. We pondered Gary Snyder’s comment: “I do not think we should even ‘think’ haiku in other languages and cultures. We should think brief, or short poems. [Haiku] has elements that can indeed be developed in the poetries of other languages and cultures, but not by slavish imitation. To get haiku into other languages, get to the ‘heart’ of haiku, which has something to do with Zen practice and with practiced observation—not mere counting of syllables.” We read some of Snyder’s haiku-like fragments and some of Hirshfield’s “Pebbles,” her tiny poems that she describes thus: “A pebble … is seemingly simple, but also a bit recalcitrant: it isn’t quite completely present until it has been finished inside the reader’s reaction.”

We also talked about some of the rules of classical Japanese haiku: the “turning” that often occurs, from outward observation to inside the poet’s mind, and the use of kigo, words or phrases associated with a particular season. We decided it would be fun to come up with a set of season words that would fit the environment of the Mendocino Coast. Here’s the start of our list. We’d welcome additions.

Whales swimming south

Whales swimming north with calves

Blennosperma spreading gold over Glass Beach Headlands