The turning of the year

Here we are at the turning of the year. It’s been a hard year in many ways. My particular concern has been the environment and natural resources. I’ve had to witness oil and gas interests take precedence over the protection of fragile landscapes, sacred cultural resources and vulnerable water supplies. Wildfires have devastated Northern California, where I live, including parts of Santa Rosa, the city where we go for many services. A huge fire now threatens Santa Barbara, in southern California, where I lived in the 1970s. Here on the northern coast, warming ocean temperatures have wrought havoc on the kelp forests and the sea creatures that depend on them. Throughout the world, as starving people flee drought-stricken lands, tribal hostilities are increasing.

Meanwhile, the days follow each other. The sun’s arc rises lower and lower in the sky, its rising and setting further and further to the south, and the darkness of longer duration. There will be a pause, a solstice or sun-standing-still, and then a return of the light, and we will celebrate, in our various spiritual traditions, a return of hope.

May you all find hope and joy in the days to come.

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

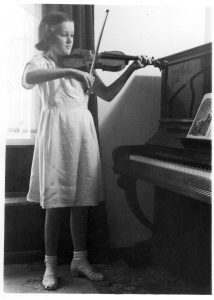

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.

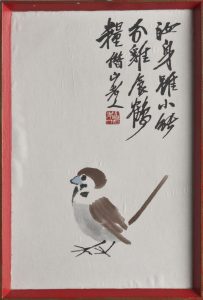

A tale of a sparrow

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

14 April 1969

A friend of Tony’s from Memorex came to dinner. A Korean boy … He is really charming, and we had a pleasant evening. One interesting thing that came out of it – Yun also reads and writes Mandarin Chinese, so was able to translate the inscription on our sparrow picture for us. Do you remember our sparrow? It is a little brush drawing that Tony picked up in a junk shop in Hawera when he was a student, shortly before reading in a magazine a story about a famous Chinese artist who was objecting to a government campaign to kill off the sparrows to improve the wheat production. He made these little posters, inscribed with sentimental stories about the sparrow. And this, as far as we can tell, is what we have got.

With the help of the Internet, I’ve been piecing together my fragments of knowledge about this period in Chinese history. What I discovered is a familiar story about well-intentioned interference with nature leading to ecological disaster.

In the First Five-Year Plan of the newly-founded People’s Republic of China, families were each given their own plot of land. In the Second Five Year Plan, begun in 1958, a new agriculture system was announced. Family farms were grouped into collective farms, making each village a single production entity in which everyone would have an equal share. Food would be provided in a communal kitchen.

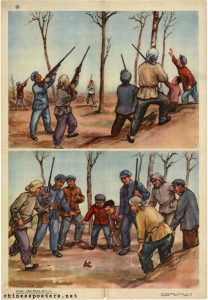

In theory, a collective farm where resources were centrally controlled should be more efficient and yield higher productivity. In practice, agricultural production figures fell. Food shortages were exacerbated by flood and drought. Believing that getting rid of sparrows, who ate grain, would improve production, Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Four Pests Campaign, which encouraged citizens to kill them, along with three other pests: rats, flies, and mosquitoes. Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks were killed. Many sparrows died from exhaustion; citizens would bang pots and pans so that sparrows would not have the chance to rest on tree branches and would fall dead from the sky. Citizens also shot the birds down from the sky. These mass attacks pushed the sparrow population to near extinction.

In hindsight, the result was inevitable. Too late, Chinese leaders realized that sparrows didn’t only eat grain seeds. They also ate insects. With no birds to control them, insect populations boomed. Locusts, in particular, swarmed over the country, eating everything they could find, including crops intended for human food. People, on the other hand, quickly ran out of things to eat, and tens of millions starved.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

Night train in winter

New Zealand’s Volcanic Plateau in daytime. Image from https://www.flyingandtravel.com/skiing-north-island-whakapapa-ruapehu/

An image haunts my mind like an old song in a minor key. From a train window late at night, a desert plateau spreads into the distance. In the foreground, scattered clumps of tussock, stiff with frost, emerge from a dusting of snow. On the horizon, three volcanic cones gleam white against the blackness. The scene is both bleak and beautiful. Tranquil even. A calmness fills me as I remember.

The year was 1968, the place the center of North Island, New Zealand, somewhere north of Ohakune on the Main Trunk Line. I was traveling by train, alone, to a funeral.

It had been a tense few months since my husband and I, with two young children, had decided to make the trip back to New Zealand, our home country, to visit our families. First there was boundary-setting to do with my mother on how much relation-visiting I would allow her to inflict on my shy infants. A few weeks prior to our departure date the children developed chickenpox, one after the other, pushing our schedule further into New Zealand’s winter and upending an itinerary that carefully divided our limited time between my husband’s family and mine. On arrival, I discovered my mother had sabotaged this division by taking a motel room in my mother-in-law’s town. Each day she ensconced herself in mother-in-law’s tiny living-room, dragging my embarrassed father and school-age sister with her. Other sisters later told me they’d remonstrated with her, but she’d insisted she had a right to see her long-gone daughter as soon as I arrived. My mother-in-law was gracious, but I was furious on her behalf.

Then fate intervened. On a night of heavy rain, my maternal grandmother’s husband stepped from between parked cars into the path of an oncoming truck. I did not know my step-grandfather, since he and grandma married about the time I left for college. But grandma had been an important part of my childhood, and she loved this man, so it mattered that I go to the funeral. Leaving the children with their father and his mother, I set out on the overnight journey. First a railcar from New Plymouth, on the west coast, which connected at Marton with the Night Limited express that ran each night between Auckland and Wellington.

I knew this train, having ridden it back and forth many times when I was in college. There was comfort in the familiar sway and smell of the overheated, stuffy carriage, the faded red plush covering high-backed seats, the clackety-clack of the wheels. There was peace too. For the first time since the children were born I was alone, with no responsibilities.

Beyond the desert and mountain vista on the Volcanic Plateau, the chuff and grind of the diesel engine became more labored as the narrow-gauge track rose into a more broken landscape, with forest a dark overhang outside the window. Then Taumarunui Station at 2:00 am, the refreshment stop, where bleary passengers streamed into the tea-room for meat pies or slabs of yellow pound cake and milky tea in thick white china cups. Sometime around dawn, a stop at Te Kuiti where relatives met me for the two-hour drive to Tauranga, where the funeral was to be held. Calmed by the journey, I willingly renewed acquaintance with uncles and cousins and aunts I’d argued with my mother about seeing.

Looking back, I understand what that spare, snow-covered landscape was telling me: that the land is vastly more important than human quarrels, that I needed to let go of my day-to-day tensions and anxieties and become merged with the wholeness of the earth.

Night of the cane toads

I recently asked my son Simon, now in his fifties, if he remembered anything of our visit to New Zealand when he was two. He thought for a moment. “I remember the frogs.” Ah yes, the frogs. Actually they were cane toads, but a two-year-old doesn’t bother with such distinctions.

Our flight from San Francisco to Auckland had a six-hour layover at Nandi, Fiji. When we arrived in Nandi at 4:00 am, we learned that the airline had very kindly provided a motel room so that we and the children could get a little rest. Tony and I looked forward to this. We were flying Qantas Airlines, and a bunch of young Australians partied all night in the rows behind us, oblivious to the flight attendant’s efforts to keep them quiet. The children, however, would have none of this going-to-bed nonsense. Their circadian rhythms completely out of whack, Simon and his brother were bright-eyed and ready for adventure.

We heard the toads first, a continuous high-pitched purring that filled the warm tropical night like the sound of a smoothly running motor boat. Then we saw them. Near the motel swimming pool stood a pole with a bug-zapping lamp attached. On the ground below, hundreds of cane toads clustered, waiting for the next flying creature to drop. The children were enthralled. Fortunately we did not allow them to go near the creatures, who can secrete a toxic poison.

The cane toad (Rhinella marina) is native to South and Central America. In 1935 they were introduced to Fiji and other places to control beetles on sugarcane plantations. The trouble was, the toads couldn’t jump high enough to eat the beetles, which live on top of cane stalks. With no natural predator in their new home, the cane toads bred in large numbers, and have proved to be an environmental disaster. They have voracious appetites, and will feed on almost any terrestrial animal and compete with native amphibians for food and breeding habitats. Their toxic secretions are known to cause illness and death in wildlife and in domestic animals that come into contact with them.

The cane toad disaster is a classic example of humans disturbing an ecological balance, inadvertently creating a new problem as they try to solve an existing one. Thinking about that tropical night makes me realize how little we still know about the complex interactions of the natural world. But on a personal, selfish note, the Fiji motel toads did provide entertainment for two rambunctious little boys.

The best laid schemes

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley

–Robert Burns

I’ll never forget how furious my mother was with me that day. I was about seven years old, and spending the day at my grandparents’ house while Mum ran last-minute errands. The next morning my parents, sisters and I were to leave on a camping trip, the first real vacation my family had ever had; Dad was an auto mechanic, and summer was his busiest time, with all the beach-goers flocking into our seaside town and needing help with their vehicles.

That afternoon I started to feel poorly. Grandma felt my forehead and promptly tucked me into bed. By the time Mum bustled in to pick me up the cause of my misery was obvious: my body covered with the red blisters of chickenpox.

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

11 May 1968

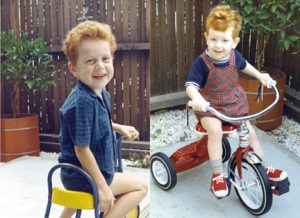

I did write to you earlier in the week, but it was obsolete before it was even posted, so I tore it up instead. Isn’t this business just typical of kids? Anyway, here is the present state of play: we have bookings … [revised details]… But this flight depends on Simon [our two-year-old] coming out in spots this weekend, or Tuesday at the latest. The chances are higher that we shall postpone again until the following week …

Here is my calculation of the odds: Incubation period 11-21 days. Say David came out in spots on the 11th day, and Simon, from the same contact, on the 21st day (i.e., next Friday) he has two weeks to have it over with.

Say Simon missed David’s contact, and gets it from David, he can come out in spots on the 11th, 12th, or 13th day, and has 11 days, or a reasonable chance, to be free of scabs. (The airline will take him if a doctor will certify that he is not contagious.)

Say Simon decides not to get it at all, he will have passed the 21st day by two days.

The only problem will be if he gets it from David after the 13th day. The 14th day is borderline; after that we would have to cancel. We are in a bit of a quandary as to what to do then … Meanwhile we are all twiddling our thumbs, and willing Simon to produce ‘chickenpops’, as he calls them. It seems such an awful thing to do to such an innocent little poppet, but so far he has remained obstinately clear-skinned and perky…

The ironic thing is that we had a mumps crisis last week. One of the children’s closest friends came down with mumps about two weeks ago. We flapped around for a while, seriously considered gamma globulin, in spite of the cost (about $60 just for shots for myself and the children). We had braced ourselves to go through with it, when at the last minute the doctor just couldn’t get hold of any, so decided to try a new mumps vaccine instead. This is a lifelong immunity, but doesn’t take full effect for a month. By this time, he hoped that the vaccine would have built up enough antibodies to resist the disease. So far it is working. It is quite interesting being guinea-pigs, and considerably less expensive, at only $5 each. So instead we get the chickenpox!

…I have just come in from a walk – after four days in the house with kids, I needed it, but have come back feeling more depressed than ever about the whole business.

Monday – Have postponed until 31 May…

20 May 1968

Believe it or not, Simon actually produced some ‘chickenpops’ today, so we have started believing again that we are really coming. … I’m still not really convinced that we will arrive, but as we are going in this Wednesday to pick up the tickets, I had better stir myself out of this legarthy.

The irony of this story is that when we finally arrived at Nandi, Fiji on our way to New Zealand, the immigration officer noticed that David’s smallpox vaccination was outdated. (You needed this at that time to get into New Zealand). In our panic over chickenpox, we has totally spaced on this detail. Fortunately the officer was kind “Just get it done as soon as you get there,” he said as he stamped our papers.

Uncles & cousins & aunts, oh my!

Recently, while reading Michael Krasny’s new book, Let There Be Laughter, I came across the Yiddish word naches, which Krasny defines as “the joy and pride a parent derives from a child’s accomplishments.” High on a mother’s list of accomplishments for her daughter would be the production of beautiful grandchildren. It was an ‘Aha!’ moment. I’d been re-reading some of my 1967-68 letters to parents (my mother saved them all and gave them back to me) and thinking about the strained mother/daughter relationship the letters revealed.

The occasion was our first visit back to New Zealand. It had been seven years since we left our birth country, and twelve years since I had spent more than a week or two with my parents. In the meantime I had earned an advanced degree, begun a career as a writer, married, moved to England, had a couple of children, moved to California. I had kept in touch faithfully through fortnightly letters but had had none of that face-to-face interaction that helps define a relationship.

I was wildly excited about the trip:

18 Sept. 1967

I have a bit of news that I have been saving up, partly because I still scarcely believe it myself – we are hoping to come for a visit to NZ about the middle of next year, probably in May. It will only be for a month – you get a cheaper excursion rate for 28 days – but hope that will be long enough to see everybody again, & for the children to sort out who all the vague names of grandmas, uncles, etc. are – David [our 4-year-old] has them hopelessly confused at the moment.

1 Oct. 1967

[On news that sisters & cousins were having babies] It will be fun to meet all these new members of the family – they certainly seem to be mounting up.

31 Oct. 1967

[re Christmas presents] Like you, finance is a bit low this year – as you can imagine, we are needing to save very hard for this trip.

My next letter has a firmer tone. With the help of a marriage & family therapist friend (thank you, Linda G.), I’ve been researching the psychology of mother/daughter relationships and discovered the Jungian concept of individuation, the process of becoming aware of oneself as a being separate from one’s parents. I also learned that tensions are normal in the parent and adult child relationship during this process of separating and setting boundaries.

17 Nov. 1967

I gather that preparations are already being made for our homecoming in May. I hope you realise that our time is going to be extremely limited. We hope to divide most of it between you & [my husband’s mother], but also must go to Christchurch for a few days, and also have friends around the country that we hope to visit. So you would do well to reckon on about a week (don’t forget flying time is included in the 28 days). This week will have to include relations too. The plan for an open day or weekend sounds a good one. I had better make it plain from the start that, apart from our immediate brothers & sisters, and possibly grandparents if they are too infirm to travel, we are not going to do any relation-visiting. For one thing, it wouldn’t be fair to the kids, dragging them round from one set of strange faces to another. If you are going to get to know them at all, which from our point of view is the purpose of the visit, we will need a quiet domestic atmosphere with as few strange faces as possible. It took David four months to adjust to living in this country. Also, two days of being an exhibition piece is about as much as T. or I could stand – we are pretty unsociable types!

Here’s where the Yiddish concept of naches comes in. Looking back, I realize now that it mattered deeply to my mother to be able to show us off. She had never seen our children, her first grandchildren, other than in photographs, and she had idealized them. But as a young mother, I was having none of it:

5 Dec. 1967

Glad you see my point about visiting relations, though reading your letter again I have a suspicion that you intend to have them turning up all the time anyway. If this is so, please think again. I know, Mum, you love to have your family about you, and find it hard to understand my attitude. But to me my family is my husband and children, and next, my parents and brothers and sisters. Now I shall be delighted to meet all my uncles and my cousins and my aunts, but since practically all of them are almost total strangers, it would be much easier on us to restrict their visits to a definite two days, and leave us free for the rest of the time to do what we came for, which is to visit you.

In my psychology reading I came across another concept, filial maturity, explained as:

1) By early adulthood, particularly in the 30s, taking on the responsibilities and status of an adult (employment, parenthood, involvement in the community), the child begins to identify with the parent.

2) Eventually, the parent and child relate to each other more like equals.

When I wrote these letters about our forthcoming trip to New Zealand I was 29. After fifty years of being a mother and a grandmother, I now understand why my mother and I were at odds. I’m sorry she had to deal with such a difficult and demanding daughter. I also know this was the way it had to be.

What place have we come to?

I grew up in a country with strict gun control laws. In New Zealand in the 1940s and ‘50s, you needed a permit and a “proper and sufficient purpose” to acquire a firearm, and all weapons had to be licensed and registered. Automatic pistols were outlawed altogether. My dad kept a rifle in a locked closet, taking it out occasionally to go hunting for feral pigs with his friends. But guns were not part of my small town landscape. Even today, New Zealand police officers do not routinely carry firearms.

Imagine my state of mind then, when the newspapers of my newly adopted country ran daily news stories about firearm-related deaths. Looking back now at government statistics, I see that in 1968 the US, with a population of 200.7 million, had about 31,400 firearm deaths. (Since the Center for Disease Control bundled multiple years 1968-1980, this is an average.) CDC, in a 1994 report, predicted that people killed by firearms would by 2003 outnumber vehicle crash-related deaths. Louis Jacobson, in a PunditFact article, verifies Nicholas Kristof’s 2015 statement that “More Americans have died from guns in the United States since 1968 than on battlefields of all the wars in American history.”

On April 4, 1968, our family had been in the US less than a year. My husband Tony was in Washington, DC for an international magnetics conference. On March 30 I wrote to my parents: He is very excited about this, especially as he hopes to meet some of his friends from England who are expected there.

About a week later I wrote again:

10 April 1968

Tony also got involved last week in America’s other big trauma – the race riots following Dr. King’s assassination. He had great difficulty getting out of Washington on Friday [April 5], but fortunately the flight crew of his plane had the same problem, so managed to catch his correct flight a couple of hours late. I gather that the conference was very successful and useful, if somewhat exhausting.

Reading these words again today, I notice the calm, distancing tone. I couldn’t tell my parents that I was terrified. Tony had described to me the view from the night sky: cities in flames all across America.

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was fatally shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, shortly after winning the California presidential primaries in the 1968 election.

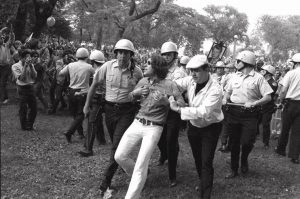

Police lead a demonstrator from Grant Park during demonstrations that disrupted the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968. (AP) Image from https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Yet more public and political mayhem was to come. In August we endured reports of the violent clashes between police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. In its report Rights in Conflict (better known as the Walker Report), the Chicago Study Team that investigated the incident stated that the police response was characterized by:

…unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night. That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring.

I have to agree with Haynes Johnson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who was covering the convention. He wrote in a 2013 Smithsonian Magazine story that the convention was

…a lacerating event, a distillation of a year of heartbreak, assassinations, riots and a breakdown in law and order that made it seem as if the country were coming apart.

A roof and a meal in 1968 dollars

While rereading letters dated early 1968 from California to my New Zealand parents, I discovered a conversation about the cost of housing and the cost of living generally. If you’ve seen the current astronomical real estate prices in the San Francisco Bay Area you will be mind-boggled at the numbers. For that matter, housing prices have also risen dramatically in New Zealand cities. (To take inflation into account, multiply the US 1968 numbers by 7.2)

The conversation started with mention that friends in the apartment complex where we lived had bought a house.

2 Jan. 1968

On Sunday we spent the afternoon at the J___s’ new house – they have managed to acquire a lovely rural acre running down to a creek – we are very envious.

26 Jan. 1968

You asked about the price of housing. Well, the J___s got theirs extremely cheaply, because of some easements on the property – power lines restrict building on one corner, and a road may possibly go down the side of it. Normally such a place would go for between $45,000 and $50,000 – they got it for under $35,000. Housing is generally pretty expensive here. If you want a genuine or potential slum you only have to pay about $18,000, but the vast majority of ordinary middle class suburban houses – about equivalent to the typical NZ suburban house – come in the range $22,000 to $28,000. New houses in this area, that is, the west side of the [Santa Clara] valley, are all $35,000 and up. Down payment is between 10%–25%. Which puts us out of the housing market for some time.

Just for comparison, what would an equivalent house in NZ cost now? The outer suburbs of Auckland or Wellington, for instance. It would also be interesting to compare costs of living – could you find out for me how much it would cost per week to keep house for a family like ours, for instance?

27 Feb. 1968

Thank you for the list of prices etc. Costs certainly seem to be fairly high. Your power bill is about the same as ours, and so is the telephone. Houses in NZ seem to be about half our price, but rents considerably lower – we are paying $160 a month, or $40 a week, and this is pretty reasonable for this area. To get a house we would have to pay $225 or more.

Your food bill is certainly much cheaper than mine. I have $40 a week for housekeeping, of which about $20 goes on groceries, $4 on fruit and vegetables, $5 on meat (and this is pretty frugal – we practically never eat steak, for instance. In fact, our standard of living hasn’t changed much from what it was in England.) The rest goes on miscellaneous sundries – sewing notions [I sewed all my own and the children’s clothes], postage, haircuts – at $3 a go for an ordinary cut it’s just well I don’t go in for sets, perms, etc., and the boys’ hair I cut myself.

…This seems to be turning into a grouch about costs, which is not really fair, as salary levels are comparably higher. At present we are managing to save about 10% of Tony’s salary, which is better than we have ever done.

Those new houses in Cupertino that in 1968 were selling for $35,000 are now listed at over $2,000,000. That’s eight times the inflation rate. Economists might say that’s the law of supply and demand.