Archive for the ‘history’ Category

Politics in an old English village

My journalist instincts kicked in when I discovered a seething political battle behind a traditional English fair, in Wraysbury, a village on the Thames west of London. In my old black filing cabinet I found a copy of the article I wrote in 1962 for my Christchurch, New Zealand newspaper. I’ve appended a transcript.

A 2014 soccer game on Wraysbury Green. Photo courtesy of Cookham Dean Football Club.

A postscript: the Wraysbury Village Association won their appeal in July 1962. A search on Google Maps shows there is still a substantial green, with playing fields and tennis courts.

LEGAL BATTLE OVER VILLAGE FAIR

In the shade of ancient oaks and chestnuts, where the sweet scent of hay rises from the scythed grass, the sounds of the fair blare out from merry-go-rounds and coconut shies. Across the green, starry with clumps of white daisies, tents and stalls are filled with people inspecting plants, basketwork, and local works of art, or watching a potter at his wheel, or quaffing ale in the refreshment tent.

Wrestlers, fencers and gymnasts display their skills, and a model train, ponies and donkeys give rides across the green to excited children. The soft fluff of dandelion seeds fills the air, and above the trees dozens of swirling balloons make patterns against the warm summer sky. Pretty girls in long skirts, frilly white blouses and straw bonnets are selling programmes.

This is an English country fair, but one with a difference. It is an act of defiance by a village threatened with destruction, a self-consciously archaic revival of an ancient right and custom against the encroachments of suburban London. Its background is a feud that has split the village in two.

Wraysbury, Bucks., was a flourishing village when the Domesday Book was written, and inside its parish boundaries, on an island in the Thames, Magna Carta was signed by King John. Now overhead the whine of airliners rising from London’s Heathrow airport vie for attention with the swooping and twittering swallows. All round the village the tentacles of London’s urban sprawl show themselves in rows of smart modern houses. Closer and closer to the village the heavy machinery of the gravel merchants turns this swampy land on the north banks of the Thames into untidy pools and mounds of gravel.

Now the old manor farm, a relic of feudal times, is to go under the hammer. Most of the farm will be broken up—“for building development and gravel extraction.”

Most of this change has been taken philosophically by the residents of Wraysbury, many of whom have themselves come to the village from the crowded heart of London. But three years ago a crisis developed. A building speculator who had bought part of what was once the village green asked the villagers to waive their rights to this patch of land.

“What rights?” the villagers asked. They discovered that when the great enclosures had taken place in the 18th and early 19th centuries, a private Act of Parliament had in 1803 safeguarded to the use of the villagers certain footpaths down to and along the banks of the Colne Brook, which runs through the village, and also the right to hold, on the Friday afternoon after Whit-Sunday, the ancient and traditional fair on the village green.

This green is now in three sections, one of which was bought by public subscription for the village. Another section was bought by the local tennis club, and the third by the building speculator.

The speculator’s plot, like his request, is insignificant in itself, but the villagers believe that a major principle is at stake, particularly as a gravel contractor at the same time asked for a waiving of rights on one of the old footpaths, in order to extend his gravel extracting operations.

The villagers’ main concern is their remaining village green. If they were to give way in the two present cases, they feel that the Act which safeguards their rights will be undermined, and they will have no means of defending what is left.

When the matter was first broached, friends of the builder called a public meeting of the residents, who turned down the request by about 300 votes to 10. The builder decided, however, to continue his scheme. His opponents formed a residents’ association to protect their rights, accused the parish council of complicity, stupidity, or both, and applied to the court for an injunction to restrain the builder.

On the other side were ranged the parish council, half of whom were replaced by the association’s nominees at the next election, and those builders who were interested in property development, and who considered that the opposition were obstructing legitimate progress.

The association won their case, but an appeal is pending. Meanwhile, they determined to revive the traditional fair, which had not been held for 50 years. The fair itself, like most English country fairs, is a relic of pagan times, when it was a feast to honour gods and heroes. With the coming of Christianity the custom was adapted to a wake, or all-night vigil, which the parishioners spent in the church. It was followed the next day by eating and drinking and rural games.

The wakes, which had by that time become very riotous affairs, were stopped by Henry VIII. Charles I revived the old custom, but took the precaution of ordering that his Justices of the Peace should be responsible for preventing any disorders. By this time the religious aspect of the feast had become of secondary importance, and hawkers and peddlers of merchandise of all descriptions began to put in an appearance.

But the right to hold a fair was still held so sacred that, even through the great enclosures of the agrarian revolution, it was preserved to the village on the remnants of common land. It is this right which the villagers of Wraysbury are defending today. They do not see their fair as a sacred feast, but rather as a symbol of their right to keep a beautiful patch of ground for their, and their children’s recreation.

The explain it in their programme, which describes the purpose of the fair:

“In these days of giant squid corporations and almost omnipotent local authorities, it is by no means impossible that what the Act of 1803 salvaged from the ruins of the old manorial system might yet get mislaid and turn up in somebody’s back yard.”

Droplets in an immigrant wave

In a 1962 article I wrote for my old paper, the Christchurch (NZ) Press, a draft of which I found in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

I have learned a healthy admiration for people of all countries who leave their homes to make a new life in another country. After three months as an immigrant in England, I realize how difficult it could be.

It took my husband two months to find a suitable job. It took us three months to find a permanent place to live. This is in a country where we, as New Zealanders, did not have to cope with language or cultural difficulties, or racial prejudice, like so many other members of the Commonwealth also drawn to the magnet of London.

We had no idea at the time of the hugeness of the immigration wave in which we floundered. To aid in post-war reconstruction in the 1950s, Britain had recruited labor from its colonies, primarily the West Indies and the Indian sub-continent. At that time people from the Empire and Commonwealth had unhindered rights to enter Britain. However, by the late 1950s, with the British economy faltering, racial prejudice reared its violent head. The Conservative Party government proposed legislation to make immigration for non-white people harder. One aspect of the proposed bill was to deny entry to dependents of immigrant workers. Before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 could go into effect, the entry of dependents into Britain increased almost threefold as families attempted to beat the deadline. Total immigration from what was known as the New Commonwealth swelled from 21,550 in 1959 to 58,300 in 1960 and a record 125,000 in 1961.

Statistics are from Paul Foot, Immigration and Race in British Politics (Penguin, 1965)

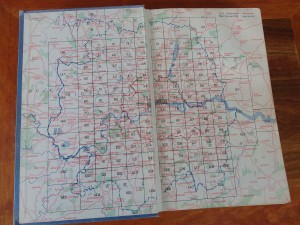

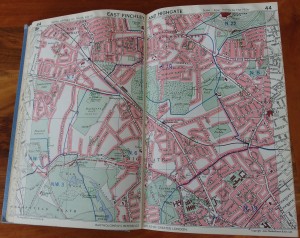

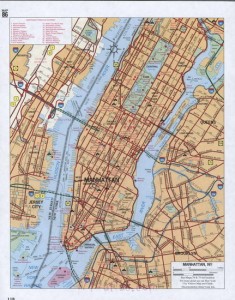

All these people needed somewhere to live. It is no wonder then that rents soared and accommodations of any sort were snapped up. While Tony job-hunted, I haunted rental agencies for a short-term apartment (or flat, as they’re called in England) and, the hefty Bartholomews Atlas of Greater London under my arm, braved the Underground and navigated the suburbs. My letters to parents are full of observations like this one:

It’s amazing how so many of the little villages that have been absorbed into the city still retain their village atmosphere – you pop up from an Underground station and could imagine yourself miles out in the country – unless you happen to be on a bit of a rise, when you see nothing but houses as far as the eye can see. One place I visited, for instance, Muswell Hill, you had to go by bus through a very extensive patch of woodland to get to it. That place I didn’t take, incidentally, because the bath was in the kitchen – covered by a lift-up board and a little frilly curtain. When I mentioned this to another English landlady she didn’t even raise an eyebrow.

My letter continues:

We have now moved out of our hotel into a bedsitter out at Hampstead, for which we are being grossly overcharged – I guess we just took it in a moment of desperation.

The rent was six and a half guineas a week (the same buying power as about $200 in current U.S. dollars.) Every piece of furniture was shaky about the legs, and the cooking facilities were two gas rings crammed into a cupboard with about six inches of counter surface. The shared bathroom was down the shabby hall. I described the landlady as

a bit of a social type – she was too busy preparing for her cocktail party last night to attend to our wants, which brassed me off considerably. Still we get on quite well with her little dog, so with a little careful handling relations might improve.

Relations did not improve. Still vivid in my mind is one of our shouting matches. I had returned from the local laundrette with clothes still damp, in spite of multiple coin feeds to the drier, and had strung clothesline around the room. In walked Mrs. Ashley-Davis. “My furniture! My furniture!” she wailed, hand to her heart. Other disputes must have followed. In a letter to parents dated May 25, after giving the news that Tony had accepted a job near Windsor, I mention that we have given notice

…after some somewhat violent disputes with the landlady, in which I managed to lose my temper – catastrophe!

Finding permanent housing proved even more frustrating. I told my parents:

…for the last three or four days we have been footslogging, railriding, bussing, and generally getting fed up in a wide arc around the area…

We moved out to a hotel near Tony’s new job. My letters for the next few weeks are full of the false hopes and discouragements of the search. Finally we got lucky: a second floor flat in a Victorian brick semi-detached house just down the hill from Windsor Castle. A roof over our heads at last!

Here’s a modern Google Maps street view of the neighborhood. It still looks much the same.

Red is the color of lost empire

In the 1940s, when I was a schoolchild in New Zealand, we used our red pencils to color in maps of the world. Great Britain, of course: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (Eire was gone by then). Huge chunks of the African continent that still had their old names and boundaries: Sudan, Gold Coast, Cameroons, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, South Africa are just some I remember. The Indian subcontinent with neighboring Ceylon and Burma. Pieces of the East Indies archipelago. Australia, our nearest neighbor. Little red dots, lots of them, for Pacific island dependencies. The big swathe of Canada. More dots in the Caribbean, and a dab for British Guiana on the South American mainland. We pressed our red pencils hardest for New Zealand, the furthest outpost of the British Empire, on which, it was said, the sun never set.

This website has a fascinating time lapse view of

the rise and fall of the British Empire.

Even as we children beamed with pride at our splendid red maps, our world was changing. By the time I moved to England in 1962, the political geography I knew as a child was obsolete. The British had retreated from the Indian Empire, leaving behind a land painfully divided between Hindu and Moslem. The red chunks of Africa rearranged themselves into separate nations. South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand declared themselves a Commonwealth, still recognizing the Queen, but independent of British rule.

Old loyalties die hard. The Union Jack still fills the top left corner of the New Zealand flag. In 1962, New Zealanders still looked to England as the “mother country” and I could write to my parents, in my first letter from London: “[W]e have finally arrived in the Heart of the Empire.”

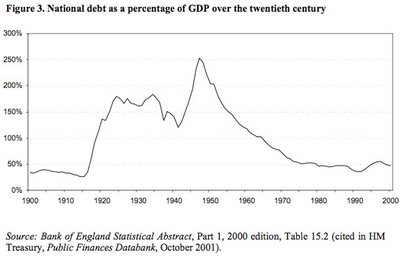

The mood I encountered in the old empire’s capital was bleak. Great Britain had survived World War II, but at an enormous financial cost, and the national debt hung like a shadow over the economy.

After the austerity of the 1950s, living standards were improving, but the country’s wealth, prestige and authority had been severely reduced. Economically, Britain was slipping behind its competitors. Relations between management and labor were bad; the newspapers were full of reports of strikes and unrest. It did not feel like a good place to be starting a new adventure.

A Kiwi at the Top

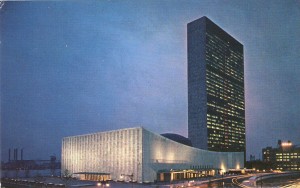

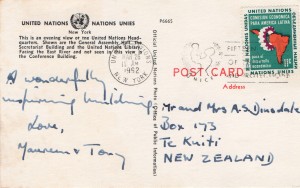

It felt like being in a fairytale. There I was, a country bumpkin on the 37th floor of the United Nations Building in New York, interviewing a man second only to Secretary-General U Thant himself.

When I left my job at The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, to go abroad in 1962, the paper’s editor handed me a list of names. “These are New Zealanders who have done something interesting with their lives. Track them down and send me back some interviews,” he said.

On the list was Bruce Turner, Controller of the UN Secretariat. In a letter to parents, I described him as “A typical Kiwi c haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

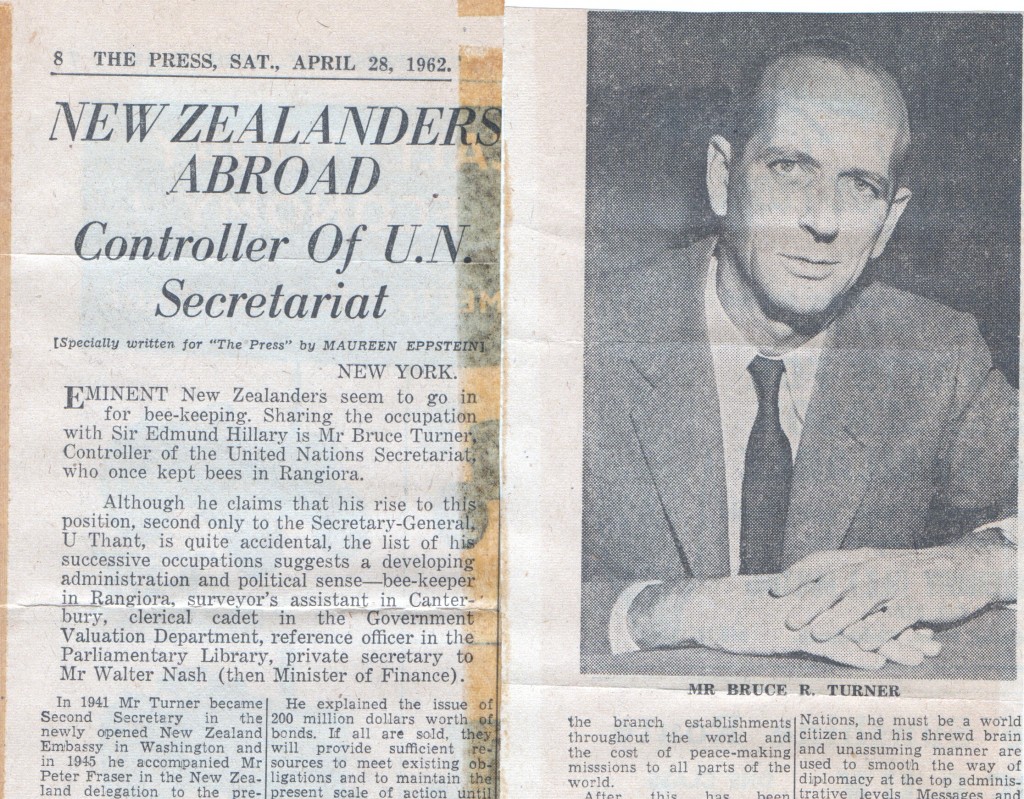

Here’s a transcript of the interview.

1962 Bruce Turner interview

Eminent New Zealanders seem to go in for bee-keeping. Sharing the occupation with Sir Edmund Hillary is Mr Bruce Turner, Controller of the United Nations Secretariat, who once kept bees in Rangiora.

Although he claims that his rise to the position, second only to the Secretary General, U Thant, is quite accidental, the list of his successive occupations suggests a developing administrative and political sense—bee-keeper in Rangiora, surveyor’s assistant in Canterbury, clerical cadet in the Government Valuation Department, reference officer in the Parliamentary Library, private secretary to Mr Walter Nash (then Minister of Finance).

In 1941 Mr Turner became Second Secretary in the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Washington and in 1945 he accompanied Mr Peter Fraser [the NZ Prime Minister] in the New Zealand delegation to the preparatory commission on the first session of the new United Nations.

“Here Mr Fraser had the misguided generosity to lend my services to the first Secretary-General, Trygvie Lie, and I haven’t been able to get out of it ever since,” Mr Turner said recently in New York.

Vast Responsibility

On him rests the responsibility for all financial aspects of the organisation’s activities. “And since everything we do involves money, this means, in effect, the whole lot. The position would be comparable in New Zealand to that of the Treasury, the Auditor-General and in some respects the Public Service Commission, all rolled into one. Sometimes I suspect that I don’t know entirely what the job involves myself,” he said.

His department prepares in advance a budget of regular expenditure. This includes the administration of the secretariat in New York and the branch establishments throughout the world and the cost of peace-making missions to all parts of the world.

After this has been approved by the Administration and Budgetary Committee of the General Assembly, commonly known as the Fifth Committee, the money is collected on a quota system, based on the capacity of each member government of the United Nations to pay. This quota is periodically revised by a committee of ten experts.

But for extraordinary expenditures, such as the United Nations Emergency Force sent to the Middle East in November 1956 and the force sent to the Congo in July, 1960, a separate budget is required, although the proportion borne by each country remains the same.

A Major Problem

Here lies one of Mr Turner’s biggest headaches. Certain countries claim that they have no legal liability for their quota of this extraordinary budget. Meanwhile, funds are running low, but the need for maintaining forces in the Congo continues.

He explained the issue of 200 million dollars worth of bonds. If all are sold, they will provide sufficient resources to meet existing obligations and to maintain the present scale of action until the end of 1963.

Mr Turner put the problem in the smoothly rounded language of diplomacy and press statements: “On the success of this bond issue depends the future of the whole organisation and its peace-keeping operations.” He broke off to joke grimly: “Oh well, if it fails, this place will be blown up and I will be out of a job.”

He spread his hands lightly round the pleasant wood-panelled room with its quiet beige and jade upholstery. Heavy curtains hid a view of the East River and Brooklyn in the early evening. On a low table, beside a bowl of spring flowers, a handsome Maori carving gave a hint of the occupant’s country of origin.

“Some day I might retire to New Zealand—that would be the normal procedure for any expatriate New Zealanders,” he said. “It would be somewhere with a warm, mild climate. Tauranga perhaps—that is not too far from my friend in Hamilton who owns a brewery.”

Meanwhile, like all other employees of the United Nations, he must be a world citizen and his shrewd brain and unassuming manner are used to smooth the way of diplomacy at the top administrative levels. Messages and telephone calls continued to pour into his office, telling of Government decisions on the bond issue. The maintenance of forces in the Congo, while still a grave problem, seemed a little more hopeful.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Country bumpkins in New York

The friends we were traveling with chose the hotel, the cheapest they could find. It was on W. 46th Street, just off Times Square. Only one thin hand towel in the grungy bathroom. What to do? We called the desk. A maid appeared, to tell us the towels were not yet back from the laundry. In hindsight, a tip might have made towels magically appear. But we knew nothing about tipping; it wasn’t a part of the culture we knew.

Breaking our 1962 journey from New Zealand to England as young married couple off to see the world, Tony and I had disembarked in New York to visit my sister Evelyn, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University in upstate New York. From there the three of us traveled by Greyhound bus to Baltimore to spend a few days with her friends Brian and Jennifer Wybourne and visit Washington, DC.

Driving with the Wybournes back to New York, where we were to board another ship bound for England, we were wide-eyed at our first glimpse of the New Jersey turnpike. In a letter to parents I wrote: “…one of the most famous of the turnpikes – 150 miles of unhindered 6-lane highway. Then navigating the streets of the city – practically all are one-way, which makes it complicated, and you can imagine the traffic.”

The letter continues: “The next morning we went up to the top of the Empire State building – early, before the mist got up. The view from the top is terrific – you can see the whole extent of New York city – which is saying something.” I look back in memory and see the young woman I was, neck stiff from craning upward at rows of skyscrapers that made deep canyons of the streets, mind agog at the level of luxury displayed in store windows. I remember wandering through several of the huge department stores, feeling lost and out of place.

One day we walked to the tip of Manhattan and back, excited to see Wall St. and Greenwich Village, and to walk on Broadway. I wrote: “We were really footsore by the time we reached the hotel, but then we had the big experience of our trip – riding the New York subway during rush hour. That was some experience. We held each other tightly, and shoved with the rest. Sardines in a can had nothing on the train – but you had to make sure you weren’t pulled out with the rush at each station.” Evelyn, who was taking us out to the Bronx to dinner with the family she was staying with, wrote in her letter home: “I deliberately engineered it to be at Grand Central Station about 5 past 5 at night. It was quite an eye-opener for them…”

On each of the other nights we had the new experience of dining in a restaurant of a different nationality, all quite cheap by New York standards, and all in the same block as the hotel – Greek, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, as well as American – hamburgers and doughnuts.

For lunch Evelyn introduced us to automats. I commented: “We found foreign food much more interesting than American – they process it and vitaminise it, and goodness knows what – the result is rather tasteless.”

In future weeks I’ll talk about other aspect of our first visit to New York: the art, the music, the experience of visiting the heart of the United Nations secretariat.

And yes, a few more threadbare towels did eventually show up in our hotel room.

Old age has its advantages

I’m taking a break this week from tales of my youthful travels to share a poem I wrote as homework in a Stanford Online class: 10 Pre-Modern Women Poets, taught by Eavan Boland. This week we studied “Saturday: The Smallpox” by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Written in 1747 in the voice of Flavia, a young beauty whose face is disfigured by the disease, the poem is a sad satire on the priorities of that era’s fashionable society. Our assignment was to write a poem using the heroic couplet form in which “Saturday: The Smallpox” was written.

Lady Mary, who was herself afflicted with smallpox, was a pioneer in vaccination for this dreaded disease. I find it particularly discouraging that 267 years later, people are still arguing about the value of vaccination against measles, a disease that nearly killed my father when he was a child.

However, my poem isn’t about the ravages of disease, but rather the emphasis on fashion still rampant today. It was a lot of fun to write.

A Grandmother Responds to Flavia

Advancing age has this one recompense,

That I can clothe myself with common sense.

Invisible already to the young,

I’m from the prison of convention sprung,

At last to dress as I have lately dressed,

I don’t wear heels; I’ve never seen the point

Of teetering at risk to ankle joint.

My fingernails are bare of chip-prone paint,

My hair goes where it wills, without restraint.

When grayness first revealed itself, I bought

Some dye, but soon discovered what I thought

Was beauty was instead a bathroom mess,

Despite my brave attempts at carefulness.

For lack of make-up, blame my allergies,

My nose rubbed naked every time I sneeze.

For lack of lipstick, blame Ms Magazine,

Which in the Seventies proclaimed with spleen

That face paint was an INEQUALITY;

If men don’t have to do it, why should we?

So now my silver hair surrounds a face

Where age’s wrinkles have an honored place.

I am content with plainness; jeans and boots

Shall walk me earthward to my simple roots.

Encountering Carnival in Panama

Panama City, March 1962

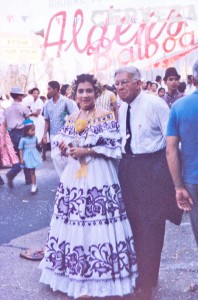

I had no idea that we’d arrive in Panama during Carnival. Even as our ship sidled into port at the end of the Pacific crossing, we could hear the sounds of it, the ramshackle city pulsing to a beat like none I’d ever heard. Once docked and allowed to disembark, we passengers pushed our way through dense crowds of people, among which wove decorated floats, costumed dancers, bands crowded onto the beds of battered trucks, men on the street beating drums or, lacking drums, the metal sides of the trucks, all singing and shouting to the heady Latin American rhythms. Sometimes a figure in fantastic costume would pass, surrounded by a group of friends singing and shouting together.

Everyone dresses up for Carnival. I was fascinated to see women wearing the pollera, the Panamanian national costume. Spanish in origin and atmosphere, the dress is of white cambric, embroidered in a bold floral pattern in a contrasting color, usually red, black or blue, each frill trimmed with a border of hand-made lace.

At roadside stalls we watched Panamanian boys scrape blocks of ice for the local sweet. They pressed the ice shavings into a paper cup, and poured over it a bright colored syrup and condensed milk. A bit tasteless, but very refreshing.

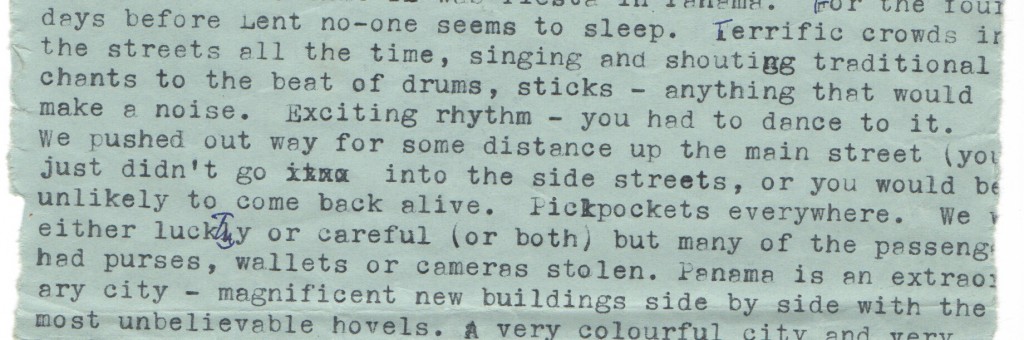

Passengers had been warned before we disembarked about the level of crime on Panama’s streets. There’s a hint of bravado in my letter to parents: “You just didn’t go into the side streets, or you would be unlikely to come back alive. Pickpockets everywhere. We were either lucky or careful (or both) but many of the passengers had purses, wallets or cameras stolen.”

What I didn’t write about was the effect on me of the incessant drums, the shouts and snatches of tune, the rhythm syncopated, hypnotic. I wanted to drown in it, swirl with the dancers forever into the glittering ocean of color and sound. But like the hawsers holding the ship to the dock, my past tethered me: syrupy fifties songs about marriage and children, strictures on proper behavior, appropriate dress. We wandered in the crowd for a day, then moved on.

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Scrabble and other equatorial diversions

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

After the storms and seasickness of the first week, we had perfect weather: sunny days, calm seas, and just enough breeze to keep things cool. I decided that ocean voyages were not so bad after all.

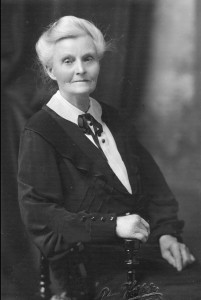

I had time to dream. When my husband Tony and I carried our bags up the gangplank of the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” earlier that month, bound for New York and then England, I felt I was walking in the steps of my role model, the great New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, who also went abroad at a young age to pursue a literary career.

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out;

At one stride comes the dark

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

I haven’t played Scrabble in years, and don’t remember what happened to our old game set. But this week we bought ourselves a new one. Nostalgia filled my heart as I pulled out from the bag a handful of little wooden tiles.

JVO photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet, which contains 55 years of letters, notes and memorabilia.

Hurricane at Sea

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

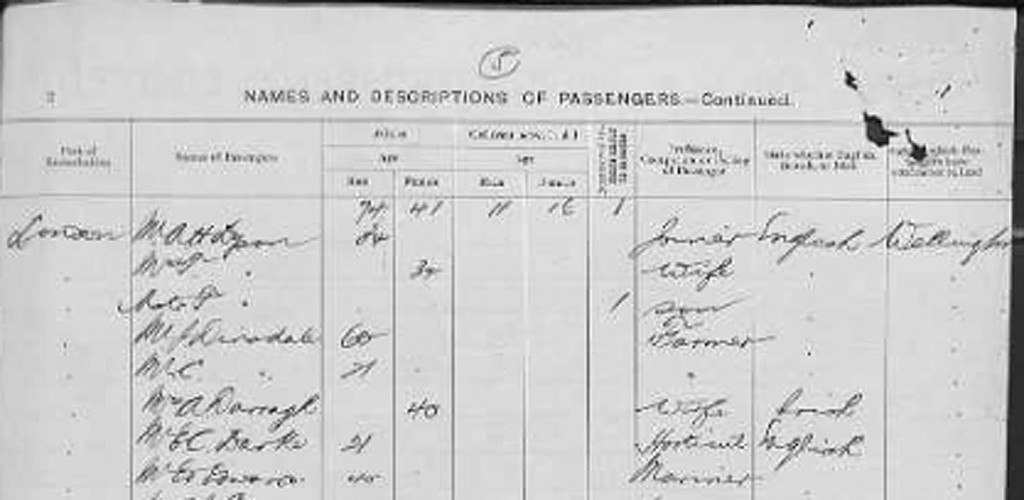

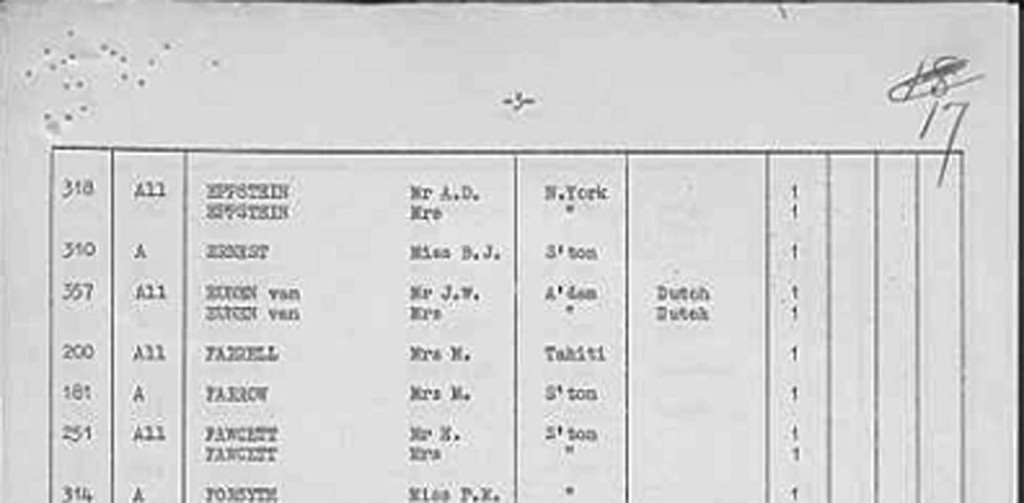

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.