A sisterhood of neighbors

Would she be able to watch my toddler for an afternoon while I went to a doctor’s appointment, I asked Margaret, my next-door neighbor in the block of new row houses we’d both recently moved into in 1965. An odd look came over her face, and a blush reddened her cheeks. A pause. “Actually, I have a doctor’s appointment that afternoon too.” Another pause. I don’t remember which of us said it first: “I think I’m pregnant again.”

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

Not having family in England to call on for help, I am forever grateful to this sisterhood of neighbors. Most of the women in our little close of twenty houses were stay-at-home mums with small children. We drank coffee together in the mornings and shared how our brains were turning to mush. Our children ran in and out of each other’s houses. We took care of each other.

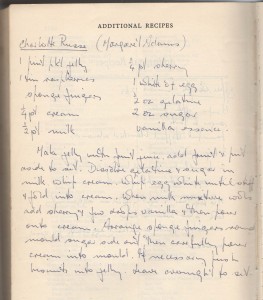

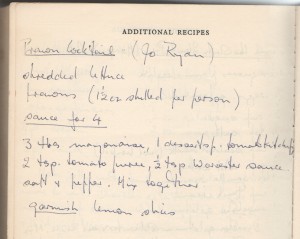

On the back pages of my English cookbook are two recipes, one for a Charlotte Russe from Margaret and a prawn cocktail from Jo, both classic 1960s recipes. I remember the occasion vividly. My husband Tony had accepted a position in California. We were waiting for our US green cards to come through –a nerve-wracking saga that I’ll write about sometime. Meanwhile, his prospective new boss was passing through on his way home to Denmark for Easter, and wanted to meet Tony. A dinner invitation was obviously required. But what to serve? In a panic, I turned to my sister-neighbors. They held my hand and helped me through planning a menu. Prawn cocktail to start, and Charlotte Russe for dessert. For the main course I probably served roast lamb, a traditional New Zealand staple.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

The woman on the moor

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The year was 1966. Knowing it might be our last year in England, our family (husband, two infant boys and me) took a summer trip through England and into Scotland, staying mostly in private homes that offered bed and breakfast. A farm in the Peak District of Derbyshire. Across the Yorkshire Dales to Huddersfield and Keithley, from whence my paternal grandfather had emigrated as a young man to New Zealand. Up to a gray stone village on the moors to take tea with a sweet great-aunt who had married and stayed behind when her siblings left, and whose knowledge of the whole New Zealand branch of the family put me to shame. The Lake District, lowering with storm clouds and redolent with Wordsworthian cadences. A stone circle near Keswick. Hadrian’s Wall, a loch in Scotland. Yellowing pictures now fill a photograph album.

The little roadside shop was somewhere in the northern hills of England, on our way home. A gray, damp day, a gray, bleak building. Nothing much else around. We all needed a break from driving, so we stopped. Quickly bored with the arts & crafts contents of the shop, our toddler and the baby drifted outside with their father. I lingered, drawn to the young woman attendant, who sat at a table threading beads into a necklace. A knitted shawl around her shoulders, long mousy hair falling in a braid down her back. We chatted. She had left an unhappy relationship and was determined to survive on her own.

She had the confidence I lacked. Brought up in a conservative culture and married young, I was struggling with a sense of powerlessness in my traditional wife-and-mother role. There were times I felt trapped, and thought of escaping with the children back to New Zealand. But this would have felt like defeat. Besides, it was impractical. I had no money to pay for fare, no clue about how I would manage on my own once I got home.

My encounter with the woman on the moor was brief. I never learned her name. But the amethyst ring symbolizes an unspoken pact between us. What I gave her was good wishes and payment for her work. What she gave me was confidence that I too could find my inner strength. This is what I remember when I wear it.

Trudging through bureaucratic thickets: a visa saga

Having lived through the experience of applying for a United States immigrant visa, my heart goes out to those who recently trudged through the bureaucratic thickets, only to be turned away at airport gates by Trump’s anti-immigration order.

Having lived through the experience of applying for a United States immigrant visa, my heart goes out to those who recently trudged through the bureaucratic thickets, only to be turned away at airport gates by Trump’s anti-immigration order.

Every immigrant’s story is different, of course. But maybe telling our story, as documented by my letters to parents during that time, will offer some insight into the process which, even in 1966-67, and even with a US company going to bat for us, was exhausting and nerve-wracking.

Born in New Zealand, we were living in England, where my husband Tony designed and tested disk drives for the rapidly-growing computer industry. He interacted with people from US companies, several of whom had shown interest in offering him a position in the US, where skilled high tech workers were in short supply.

9 Aug. 66

p.s. Have you got my B.A. or M.A. certificate? If so, would you please send them airmail.

A complication was that when we left New Zealand in 1962, we boxed up belongings we didn’t think we needed to take and left them in a friend’s basement. Those friends sold their house and moved, sending the boxes to Tony’s mother, who sold her house and moved, sending them to my parents, who sold … By this time they were (we hoped) with my sister, Evelyn.

A complication was that when we left New Zealand in 1962, we boxed up belongings we didn’t think we needed to take and left them in a friend’s basement. Those friends sold their house and moved, sending the boxes to Tony’s mother, who sold her house and moved, sending them to my parents, who sold … By this time they were (we hoped) with my sister, Evelyn.

22 Aug. 66

Don’t bother any more about the degrees. …we are going to rely on a statement from the university registrar instead. It is for American visa – we need proof of special qualifications etc. to get onto special entry list. However, there is no hurry as yet, as American job is still a mirage on the horizon – needless to say we are both a bit edgy with all this uncertainty.

An excellent job offer from a Silicon Valley company came through in early October, and we put our house on the market immediately.

An excellent job offer from a Silicon Valley company came through in early October, and we put our house on the market immediately.

17 Oct. 66

The property market is very depressed here at the moment … so we can only hope for the best.

We don’t expect to leave until after Christmas anyway. The visa will take quite a few weeks to come through, & Tony can’t give his month’s notice until he gets it.

… After so many months of waiting around, we are finding it hard to believe that it has actually happened.

31 Oct. 66

We had our first viewer for the house yesterday….

You may have heard that we have had a delay over visas – U.S. authorities have stuck over this question of Tony’s degree & they insist on the fancy bit of paper. I wrote to Evelyn last week, so hope she has managed to do something about looking for it. Could you find out how she is getting on? It is possible she may still be assuming that it is in a mailing tube – it ain’t necessarily so – it could be flat in an envelope – or anywhere. Another thought – has she got all our things, or has Mrs. L. still got some? It really is urgent that it be found.

Apart from these problems, things are going quite well. We had a note from the removal firm the other day asking when we wanted them to come in – it seems that everything will be packed for us, transported, & unpacked at the other end – unheard-of luxury!

Having gone through every box, Evelyn finally found the degree certificate in a box labeled “Dining-room stuff.” She registered the package and mailed it with first class air mail postage.

Having gone through every box, Evelyn finally found the degree certificate in a box labeled “Dining-room stuff.” She registered the package and mailed it with first class air mail postage.

12 Nov. 66

I suppose you will have heard of the latest little crisis – bloody N.Z. Post Office managed to send the degrees by ship, due to reach us about Christmas! However, it mightn’t be disastrous. B.Sc. sent by Mrs. L did arrive safely, & the firm are cabling the university to send a duplicate of the degree. But it has got to the stage where I am beginning to wonder how much else can go wrong before we actually leave.

15 Dec. 66

…[Have] had another difficult week – actually, I had been putting off writing until we got our affairs a bit straighter. Anyway – on Monday we learned that the visa petition had not yet been filed – they are still waiting for the M.Sc. degree. The ship was supposed to berth yesterday, but as the mails are already in chaos with the Christmas rush, heaven knows when it will turn up. So, having found out where the petition had got to, we thought we might as well check up on the time scale from the embassy. Here we got a horrible shock – we were cheerfully informed that it was going to take five months from the time the thing was filed in San Francisco – don’t ask me how they manage to stretch the red tape that far – that’s just what they said. Contracts half-way through being signed for sale of house – still legally possible to back out – just – but very inconvenient for everybody else, so we are going on with sale, & still negotiating a deferment of the completion date. Even so, we will probably have to find somewhere else to live for a while, which is going to be a bit of a problem. Tony very depressed at the thought of staying at [his current job] for another six months, still waiting to hear whether California are prepared to wait that long.

30 Dec. 66

How up-to-date are you with our plans? The degree has been sent to America, we haven’t heard yet whether it & its associated papers have been presented to the authorities, we have until the middle of April to get out of the house, & the name of someone in the American embassy whom it is possible (possibly) to push to get a visa sooner, and at present are gathering together all the documents (in triplicate) we require, such as birth certificates, marriage certificate, photographs, etc.

18 Feb. 67

I forgot to tell Evelyn that we have received a letter of apology from the Postmaster-General, though no compensation – didn’t really expect it!

Trying to get information about the status of our application proved almost impossible. Before 8:00 am, the phone at the US Embassy would ring and ring. From 8:00 am to 5:00 pm we’d get a busy signal. But finally, one day I got lucky.

Trying to get information about the status of our application proved almost impossible. Before 8:00 am, the phone at the US Embassy would ring and ring. From 8:00 am to 5:00 pm we’d get a busy signal. But finally, one day I got lucky.

28 Feb. 67

You’ll have to excuse me if my letters are a bit erratic in the next few weeks. We have to be out of the house in six weeks, and it is just possible that we may be leaving for America about then. The papers arrived from San Francisco last week. I don’t think I told you that we had the petition changed a few weeks ago, on the advice of the American consul in London. We had applied for 3rd preference – for those with degrees, etc., but the waiting list for this category goes back to last September for NZers – as there are only 100 immigrants a year total [from NZ] and 10% for this preference, this is not surprising. Anyway, he suggested trying for 6th preference – skilled workers not easily available in U.S., for which Tony, being an electronics engineer, would qualify, & for which there are places available now for NZers. So a frantic dash to London by me, to bring back yet another lot of forms to fill in. Can you remember all the addresses you’ve lived at since you were 16? …

15 Mar. 67

The petition has now gone for clearance to Wellington (checking up on our murky past). I don’t doubt there will be another delay, in which case we will have to move into a flat or something here. The estate agent who sold the house is looking for something for us, but I expect we shall have to pay through the nose for it.

We were lucky to find a furnished flat. On April 14 packers moved in and packed our household goods for shipment to California. We took with us only the clothes for ourselves and the two children (ages three and one) that would fit into suitcases weighing under the economy class limit, and borrowed a few items from friends, such as a cot and stroller for the baby.

We were lucky to find a furnished flat. On April 14 packers moved in and packed our household goods for shipment to California. We took with us only the clothes for ourselves and the two children (ages three and one) that would fit into suitcases weighing under the economy class limit, and borrowed a few items from friends, such as a cot and stroller for the baby.

15 April 67

… The clearances have now arrived… Now we only need a quota number from Washington, a medical check & formal interview, and that is the lot. At least we have this place until the end of May, which gives us a breathing space.

1 May 67

Believe it or not, we now have immigrants’ visa to the United States. We spent all day at the Embassy today. Having got up about 5:30 in order to be there by 8:30 as instructed, eight hours of sitting around – though I must give them credit for having things reasonably well organised, considering the numbers of people they had to get through. We were through the whole rigmarole by about three o’clock, & they offered to post the visas out to us instead of making us wait around with the kids for another couple of hours while they finished the processing – offer gratefully accepted. Actually, the kids were extremely good, considering David’s boundless energy & Simon’s lack of sleep. We were well stocked up with sweets & biscuits & story books, & of course there were plenty of other children to play with…

We are booked to leave England on Sat. 20th May, flying direct to San Francisco over the pole.

My letter of 18 May 67 speaks of farewell visits with many friends. At the last minute I learned that the company was flying us out first class, so I could have had more of the children’s gear with me for the last few weeks. But that was a minor irritation compared with the relief of having the ordeal over with, and gratitude that the Californian company kept the job open for Tony all those months. I wish all today’s visa-holding immigrants and visitors could have an equally happy ending to their story.

My letter of 18 May 67 speaks of farewell visits with many friends. At the last minute I learned that the company was flying us out first class, so I could have had more of the children’s gear with me for the last few weeks. But that was a minor irritation compared with the relief of having the ordeal over with, and gratitude that the Californian company kept the job open for Tony all those months. I wish all today’s visa-holding immigrants and visitors could have an equally happy ending to their story.

Fight or flight: an expatriate ponders

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

In this period of political unease in the US, when many have expressed a wish to go live somewhere else, I think back to our last few years in England in the mid-1960s, and how alienated we felt then.

An economics text for UK students cites several reasons for the dour mood of the country in those years. Author Tejvan Pettinger writes:

Despite higher economic growth, the UK performed relatively poorly compared to major competitors. UK productivity growth was relatively lower due to several factors. such as:

- Lack of willingness / ability to innovate

- Poor industrial relations with a growing number of days lost to strike action. Some argue this was exacerbated by Britain’s class system.

- Trade unions effectively blocked efforts at reform.

- Complacency.

- Lack of public sector infrastructure.

Even though we might have returned to New Zealand then, our lives did not take that turn. In my old black filing cabinet I found a letter to my parents that lays out the situation.

19 July 1966

… [W]e are still unsettled about what we are going to do with ourselves. We did have serious ideas of returning to New Zealand, but I am afraid that is now dropped through lack of interest on the part of N.Z. firms. We are feeling rather sour about the whole affair, especially as N.Z. is always griping about the country’s young brains staying away in their thousands. A year ago Tony made a private enquiry to I.C.T. (NZ) asking about the prospects of getting a job, and did not even get the courtesy of a reply. Then six months ago head office in London offered to arrange a transfer for him. After much prodding, official letters to N.Z. eventually got answered, but in such unsatisfactory terms that no-one knew quite what they wanted. It has taken six months for N.Z. to agree to take Tony, but they have made it plain that they consider he is being foisted on them by London, and that they are still suspicious of him. Their terms are that he is to have a year’s training in computer systems, and not until “they see how he gets on with the training” will they consider discussing position or salary. Since Tony is one of I.C.T.’s top authorities on computer tape, and already has a big general background in computer systems, he has taken this as a not-so-polite brush-off and told them what they can do with the job. If he were in his early twenties, without family, and determined to get back, it might have been different. But at his age—rising thirty is a critical age in his line of industry, since the job decisions he takes now will set the line his career is to take. So you see he just can’t afford to throw away yet another year on a job that might still not eventuate, and would probably be a frustrating backwater if it does. Other computer firms in N.Z. take much the same line—not interested enough to get him an interview in London, just “drop in when you get to N.Z. and we will see if there is anything doing.”

Meanwhile, he is still negotiating for a job with an American firm, which might mean going to live in California, but nothing has been settled yet, We feel it is time we got out of this country—the present economic crisis is just a symptom of a general decadence and backward-looking attitude, and we can’t see any future for Britain.

You mentioned your feelings towards Britain as a spiritual home—I can understand this, and think it is one of the main forces that pushes young people into coming over here. I think it is this thing about historical roots—it gives a wonderful sense of history and continuity to visit places that have been lived in for so long by so many different peoples. But it is necessary to distinguish between this feeling and the present political reality. Modern Britain doesn’t care two hoots about New Zealand—it is either confused with Australia (well, they are both on the other side of the world, what does it matter?) or else N.Z. is regarded as some sort of idealised paradise where it is never rainy or cold, and where they would like to go to escape from reality. As a political or economic entity it just doesn’t exist. And while N.Z.ers continue to believe that it doesn’t exist either, except as an offshoot of Britain, there is not much hope for its future, and the young brains will continue to stay away in their thousands.

Which makes us more or less permanent exiles, at least spiritually. But if we do go to America, it is probable that Tony will be earning enough money for us to afford the occasional holiday in N.Z. I feel very sad that the children do not yet know their grandparents, but that is one of the penalties of our decision. I hope you will understand.

Robin redbreast on a fence

I still ponder why it meant so much, that Christmas morning in England in the 1960s, that a robin sat on the back fence. The field behind the fence was white, the fence wires thick with hoar frost, and the little red-breasted bird made the scene perfect. Finally, I told myself, a ‘real’ Christmas.

I have tried for many years to clarify my feelings about the disconnect between the traditional trappings of the season and my experience of growing up in New Zealand, where the seasons are reversed. My childhood Christmas memories are of summer: the tree laden with oranges in my grandmother’s garden where we hung our presents and picnicked on the lawn; the scent of magnolia blossom outside the church on Christmas Eve.

Also the Christmas cards with their images of snow (which I’d never experienced) and yes, the English robin. I knew about robin redbreast from the old nursery rhyme, but until that Christmas I hadn’t seen one.

Now on the coast of Northern California, I have a different understanding of how to celebrate the winter season. Our multicultural society recognizes many winter festival stories and traditions: the birth of Jesus in a stable, the menorah candles of Hannukah, the Swedish light-bringer St. Lucia, the gift-bringer St. Nicholas (known also as Santa Claus), and many others. The celebration that holds the deepest meaning for me now is Winter Solstice, the return of the light. From summer to winter, I note where on the horizon the sun sets, and how the darkness grows. Even as clouds gather, the place where sun disappears into ocean fogbank moves steadily to the south. When the prevailing westerly wind shifts to the southeast, I know to expect the winter rains. Sometimes a shower or two, sometimes, such as this past week, a prolonged deluge that floods rivers, downs power lines, and closes roads.

Meanwhile, the earliest spring flowers are breaking bud, and over-wintering birds gather hungrily at my feeder: Steller’s jay, spotted towhee, hermit thrush, acorn woodpecker, hordes of white-crowned sparrows. I love them dearly. I am happy that I have learned to understand the connection between the flow of seasons and human efforts to explain them with stories and festivals. And I still have a place in my heart for the memory of that cheery robin redbreast who brightened an English winter.

A season for love (and cake)

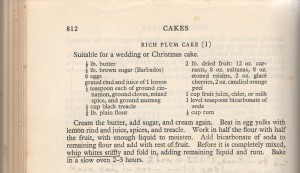

What I loved about living in England as a young woman in the 1960s was the traditions around the holiday season. On foggy street corners in London, vendors with portable braziers sold roasted chestnuts, hot in the hand, but so good. Butchers’ shop windows would fill with huge hams, neighbors’ kitchens be redolent with the aroma of figgy puddings steaming on stove tops. I would pull down the English recipe book my mother-in-law had given me and assemble ingredients for my Christmas cake: an assortment of dried and candied fruit, spices, juice, eggs, butter, brown sugar, treacle, flour, and the all-important dash of rum.

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

Making a proper English fruitcake is a multi-day affair. First, the careful preparation of the tin and timing of the baking so that it doesn’t go dry. My Constance Spry Cookery Book devotes several pages to these matters. Then the making of the cake itself. Several days later, in preparation for icing, the cake is brushed with a warm apricot glaze. My cookbook declares:

The object of this protective coating is to avoid any crumb getting into the icing and also to prevent the cake absorbing moisture from the icing and so rendering it dull.

Next comes the layer of almond paste or marzipan, rolled out like pastry and smoothed on with the palm of the hand. A day or three later comes the smooth base coat of royal icing, made by mixing egg whites and lemon juice with the sugar. When this layer is perfectly stiff and hard the decoration is piped on.

When we moved to California, I continued to make Christmas cake for a few years, until I realized that fruitcake in America is the butt of seasonal jokes and that my lovingly prepared cake sat in the pantry scarcely touched. I am grateful that until his death a few years ago, my late brother-in-law Derek Heckler, who lived not far away, continued to bake and share a splendid traditional cake.

As earth and sun roll toward another pausing time, let us remember dear friends and family members now gone, and reach out in love to those still with us. However you celebrate the season, may it be filled with the traditions you hold dear.

Oh, to be shoe-less in the summer sun

My sister Alison’s family, gathered in New Zealand for Christmas. It’s summer there, that time of year. Note the absence of shoes.

My old black filing cabinet has yielded a treasure: the carbon copy of a 1960s letter to a newspaper editor. Reading it again, I’m struck by how much it reveals about my homesickness for the more casual lifestyle of New Zealand and my resentment of the strictures of English custom. I was reminded of these differences when my sister Alison, who lives on a beach north of Auckland, posted on Facebook a photo of her gathered family, and American friends of the family joked about the lack of shoes. Here’s the 1964 letter:

The Women’s Editor

The Guardian

Manchester

Dear Madam,

As a fellow colonial I share [Guardian feature writer] Geoffrey Moorhouse’s feelings about English clothing habits. The conformity begins at an early age. This summer my one-year-old toddler and I have been subjected to cold stares and even sarcastic comments from total strangers. The cause is his shoe-less feet. I am obviously considered a poor mother, for not providing leather for his feet, and looking round, I noticed that even during the hottest days, while my infant sat comfortable in only napkin and sunhat, most of his contemporaries were firmly laced into heavy shoes, and many were even inflicted with neatly buttoned shirt and tie.

I am not against shoes on principle. Now that the weather is turning cold, my son wears shoes and socks with his long trousers. But I do object to this pressure to dress young children according to society’s idea of respectability, disregarding the dictates of the weather.

I don’t go barefoot in Mendocino. It’s cold here, and there’s burr clover and native blackberry underfoot. But sometimes I miss those carefree New Zealand summers of my youth.

The red stain of near disaster

Whenever I see old blackberry canes, dark red as the stain of their summer juice, I remember blackberrying in England when my son was small, and a dark red guilt sweeps over me. I described our expedition in a letter to parents:

8 Oct 1965

We went blackberrying on St. Ann’s Hill, not far from here. Got a lovely lot—have been busy making jelly, pies, etc. David had a wonderful time—it was so sweet to see the solemn single-mindedness with which he set about collecting his berries—and he didn’t eat a single one until Tony offered him a handful—to comfort him when he tumbled down a slope into a patch of brambles.

Modern American parents would probably be horrified at how lackadaisical we young mothers in England were about supervising our children’s play. Once the daddies were gone to work, our little close of twenty-eight row houses was almost completely free of traffic. The kids, twenty of them under school age, ran in and out of each others’ houses and romped together across the grassy front yards.

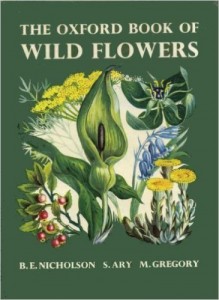

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

While Tony, who had come home from work for lunch, went to tell the mother of the other child what had happened, I tried everything I knew of to make our baby throw up. Nothing worked. We called an ambulance. Since I was within a week or two of giving birth to our second child, a neighbor, seeing the ambulance, came over to wish us well. I am still grateful that when she learned the story, she called the police, and still guilty it hadn’t occurred to me that other children might be involved. Some days later I wrote to parents:

Watercolor illustration by Barbara Nicholson in The Oxford Book of Wildflowers, Oxford University Press, 1960. Shown are: Comfrey, Common Mallow, Musk Mallow, Deadly Nightshade, Duke Of Argyll’s Tea Plant, and Woody Nightshade.

13 Oct. 1965

The police organised all the rest of the kids in the close whose parents couldn’t prove they were somewhere else that morning into another convoy of ambulances for a mass stomach pumping session. About a dozen altogether involved, of which four (including David) were confirmed cases, though they decided to keep the whole lot overnight for observation, just in case.

Meanwhile the newspapers had got hold of the story. We refused to see them at the hospital, but when we got home about 7:00—completely exhausted, & having had nothing to eat since breakfast—we were invaded by a posse of reporters. A highly garbled & exaggerated account appeared the next day. I suppose it’s not every day one makes the front page of the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, & the BBC News, but I shouldn’t care for the honour to happen again.

Anyway, the story ended well—all the kids were discharged the next morning, with none but the hospital staff any the worse for wear—in fact the sister-in-charge of the children’s ward where the confirmed cases were confessed that she hadn’t known that four such tiny boys could get so involved in riots and punch-ups all up and down the ward, and they were very pleased to see the back of them.

Fingernails on glass

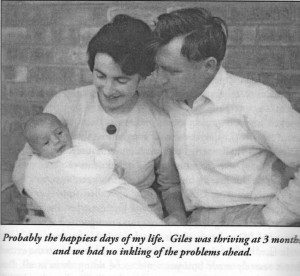

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

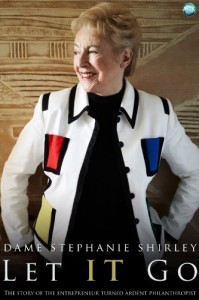

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012

Furnishing a house, 1960s style

A magazine clipping tumbles from a November 1964 letter from England to my parents. It’s the picture of a dinner service I won in a menu-planning competition. Looking at the geometric pattern on the dishes, I realize that the way we furnished the row house we bought that year has many elements of what is now recognized as a distinctive 1960s aesthetic: bold shapes and strong colors.

Having limited funds, Tony and I refurbished or made many pieces of furniture. The dining table he made was a heavy white plastic-veneered slab with straight, varnished wood legs. He built, and I upholstered, a sofa and side chairs with squared-off, simple lines, a copy of a set we particularly liked, but whose price was prohibitive. I made all the curtains from fabric purchased at Heal’s of London, the store that carried the trendiest of household furnishings. I wrote:

8 August 1964

The sitting room curtains are quite magnificent – deep orange flame colour, with a pattern called “Armada,” the formalised ships’ hulls giving the impression of a dark horizontal stripe.

A shag (another 1960s design element) area rug that matched the curtain’s colors helped warm up the coldness of the room. After battling the developer over the house’s color scheme, we had compromised on gray vinyl tile floor and plain white walls. In the kitchen and dining area, we covered the white with a geometric wallpaper. A photograph reveals more geometrics: the gray and white kitchen curtains, the cups and saucers on the counter.

We still have one platter from that dinner service I won. A few other items, mainly metal, have survived the years. A pewter jug purchased on board ship during our emigration from New Zealand to England still sits on our kitchen windowsill. To the right of the dinner service picture, behind a porcupine of cheese chunks on skewers, are familiar objects: salt and pepper shakers just like the ones we still use every day. I guess we, like these furnishings, can all be labeled “vintage.”