When anger management issues become art

Alec McCowen as the Fool, Paul Scofield as King Lear, RST 1962. Photo from the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive

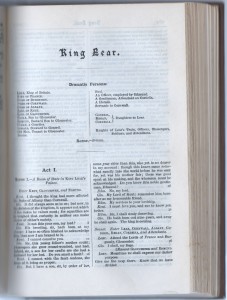

Even today, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 1962-64 run of King Lear, directed by Peter Brook, is considered by the company’s actors the finest performance they have ever put on, and Paul Scofield’s role as Lear one of the greatest ever performances of this challenging role. I count myself incredibly lucky to have seen it. Tickets were in such high demand that the theater ran a lottery. Friends scored three of the precious cardboard chits in February 1964 and invited me to join them. Leaving the baby at home with my husband, I eagerly boarded the London train.

I had studied Lear in high school, but it was in the context of cramming for a national scholarship exam. The wild language of the storm scene as Lear descends into madness thrilled me, but I was more concerned with how I would write an essay about “objective correlative,” the idea that the storm as an outward happening can correspond to an inward experience and evoke this experience in the reader. Even so, the play’s themes resonated. At a sheltered seventeen, I knew little about sexual jealousy—married sisters fighting to the death over the attentions of a lover. But I knew about families, that instinctive knowledge about which of their offspring a parent loves the most, and competition for approval from the father.

The plot of Lear interweaves stories of two dysfunctional families: King Lear and his three daughters, the Earl of Gloucester and his two sons. A man prone to towering rages, Lear banishes a devoted daughter who has refused to express her love for him in the flowery language her sisters have used. Lear divides his kingdom between the two remaining daughters, Regan and Goneril, proposing to divide his days between them. Once in power, the daughters try to control him and his retinue. Furious, Lear takes to the outdoors where, in a raging storm, he descends into madness, accompanied by his fool and, in the guise of a madman, Edgar, the elder son of Gloucester, who has been framed by his younger brother Edmund. Meanwhile, Edmund is paying court to both Regan and Goneril. In the end all the principal characters are dead, except for two of the good guys, Edgar of Gloucester and the Duke of Albany, Goneril’s husband. Albany closes the play:

The weight of this sad time we must obey;

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest hath borne most: we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.

Paul Scofield was breathtaking as Lear. On the Shakespeare Blog I found quotes from reviews of the time:

Scofield’s gravelly voice found its perfect setting in the harshness of Brook’s King Lear. The Daily Telegraph review of the stage production commented on his “unsentimental, awesome, rasping delivery” and the depiction of a “society only one degree removed from savagery”. The Times commented on his “grating low tones, the powerful air of authority”.

I missed the last train back home to Windsor. Curled up with a blanket on my friends’ couch, I could not sleep. I watched the glowing embers of their hearth fire fade to black as I replayed over and over the intense emotions of this great performance.

Maureen,

So well written. You had a “once in a life-time experience.”

Your remembrances are delightful .

How glad I am you have had this experience. We’ve been going to the Globe quite a bit recently in London and I’m always impressed at how multi talented so many actors are. Ray Fearon was a particularly gripping Macbeth when we saw him last month.

I feel I’m there with you, Maureen! How marvelous!