Archive for the ‘memoir’ Category

Red is the color of lost empire

In the 1940s, when I was a schoolchild in New Zealand, we used our red pencils to color in maps of the world. Great Britain, of course: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (Eire was gone by then). Huge chunks of the African continent that still had their old names and boundaries: Sudan, Gold Coast, Cameroons, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, South Africa are just some I remember. The Indian subcontinent with neighboring Ceylon and Burma. Pieces of the East Indies archipelago. Australia, our nearest neighbor. Little red dots, lots of them, for Pacific island dependencies. The big swathe of Canada. More dots in the Caribbean, and a dab for British Guiana on the South American mainland. We pressed our red pencils hardest for New Zealand, the furthest outpost of the British Empire, on which, it was said, the sun never set.

This website has a fascinating time lapse view of

the rise and fall of the British Empire.

Even as we children beamed with pride at our splendid red maps, our world was changing. By the time I moved to England in 1962, the political geography I knew as a child was obsolete. The British had retreated from the Indian Empire, leaving behind a land painfully divided between Hindu and Moslem. The red chunks of Africa rearranged themselves into separate nations. South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand declared themselves a Commonwealth, still recognizing the Queen, but independent of British rule.

Old loyalties die hard. The Union Jack still fills the top left corner of the New Zealand flag. In 1962, New Zealanders still looked to England as the “mother country” and I could write to my parents, in my first letter from London: “[W]e have finally arrived in the Heart of the Empire.”

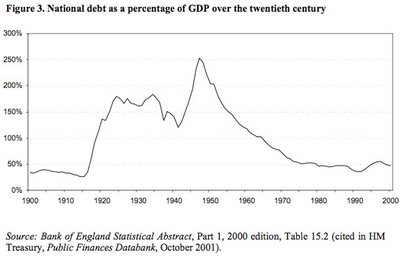

The mood I encountered in the old empire’s capital was bleak. Great Britain had survived World War II, but at an enormous financial cost, and the national debt hung like a shadow over the economy.

After the austerity of the 1950s, living standards were improving, but the country’s wealth, prestige and authority had been severely reduced. Economically, Britain was slipping behind its competitors. Relations between management and labor were bad; the newspapers were full of reports of strikes and unrest. It did not feel like a good place to be starting a new adventure.

Discovering the familiar

When I first went to London, I already knew it, or thought I did. The literature I studied growing up was English literature – novels by writers who lived in England and wrote about English life. From them I learned to find my way around London in my imagination. When I finally walked the London streets in 1962, I recognized names every time I glanced at a signpost. From Dickens I’d learned about the Inns of Court and Chancery Lane. I knew that Savile Row was filled with bespoke tailors, though I had only a vague idea what “bespoke” meant. Bond Street was where expensive jewelry was purchased by upper crust people who visited expensive doctors on Wimpole Street. Carnaby Street was where fashionable young people bought the latest fashions. As a newspaper reporter, I revered Fleet Street, where the great London dailies were headquartered.

The BBC world news, which in New Zealand we listened to on the radio every day, opened with the chimes of Big Ben, the clock at the Palace of Westminster, where the British Parliament met. I knew the sound, but still could write in amazement to my parents: When Big Ben strikes the whole street reverberates.

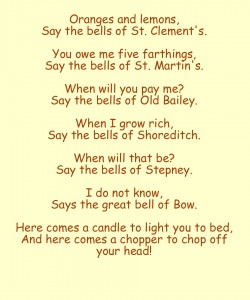

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

Here’s a Wikipedia page that includes a recording of the St. Clement Danes bells.

I wrote in my notes:

[V]ery difficult not to associate names of places in London with famous songs about them – find myself starting to hum the songs as I read the names.

We went to Buckingham Palace, of course, and I thought of my childhood book-friend Christopher Robin:

They’re changing guard at Buckingham Palace –

Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

Alice is marrying one of the guard.

“A soldier’s life is terrible hard,”

Says Alice.

My memory of those first few days in London is a sense of wonder and excitement as places became real. At the same time, there was a disconnect. I had to let go of expectations that special buildings, Sir Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s, for instance, were set off from other buildings, up on a pedestal, giving off a radiant glow. Reality was grimy walls and a crushed cigarette packet in the gutter. I wrote:

Peculiar sensation frequently of almost having been here before – not the usual one, connected with place, but connected with names – so familiar, and the outlines themselves so familiar, except that until now we had not known how they stood in the context of the rest of the city. –so this is Big Ben – so this is St. Paul’s – and we know they are, we have always known them, but we did not know that we would find them just here, with this office building on this side, and that park or square on the other. To walk down to the Embankment, and just happen to come upon Cleopatra’s Needle, standing so casually by the river. Somehow I had expected the great tourist attractions to be set apart, and gazed at always in awe. It is a jolt to realise that millions of people live and work alongside them every day of their lives, and take them so much for granted that they hardly see them. They leave the gawking to the tourists, who pour in by the busload, scatter their trash, and depart. The permanent thing is the life that goes on all around these not so very sacred objects, and of which they form a part.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Navigating the spider web

When Tony and I finally arrived in London after our weeks-long journey, our college friends Bill Moore and Robert Ludbrook met us at Waterloo Station. I felt like hugging them both, but thought they might be embarrassed, I wrote in my notes. New Zealand men of our time did not go in for overt displays of emotion.

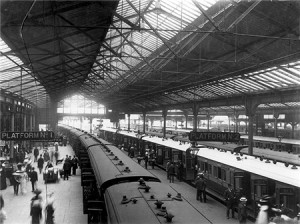

An early 20th century view of Waterloo Station. It looked much the same in 1962. Image from http://www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/

Robert spoke of his and his wife Miriam’s “traumatic experience” when they arrived. They sat for three hours in the huge Waterloo station, not knowing whether they were on the right platform, not sure what to do, or even if they could get to Derby, in the middle of the country, where Miriam’s parents lived. Their ten-month-old baby was crying from hunger – none of them had eaten for three hours. They knew no-one in the city. “I decided then that no-one I called my friend should suffer the same fate,” Robert said.

Waterloo Station is part of a transportation network that on a map looks like a giant spider web with the heart of London at its center.

The trains link to London’s famous Underground system, with which I became very familiar in the next few weeks as I searched for short-term accommodation while Tony job-hunted. I found these notes in my black filing cabinet:

Several days [after our arrival] I returned to Waterloo, and could not remember ever having seen the concourse of the station before, yet we must have passed through it on our way to the underground platform. I can remember the way the train came into the main platform – rows of long platforms jutting out into the track, with the entrance at the head of them, and the high wrought iron and glass ceiling, very dirty, overhead.

And I can remember standing on the underground platform, although that memory rapidly becomes confused with standing on other underground platforms, all confusingly similar. Always the same smell, compounded of dust and disinfectant and human bodies, always the same roar of the escalators, the same draughts of air rushing in or out, and the airless feeling when a train has passed, the rattle and screech of the trains grating on the ear-drum and jangling the nerves. The hypnotic movement, grinding to a halt at stations, and the doors swishing open. Some go in and some go out, but they are always the same people.

It is very easy to miss your own station if you do not concentrate very hard. The signs are easy to follow – in the station itself you do not get lost unless you are very blasé and think you know where you are going – but all the stations appear exactly the same – it is just that in each the maze of tunnels is different. But once on the right train you feel that you are safe, that you can relax for a while from the struggle of finding your way about. This is the most dangerous of all, as before you know what has happened, the train will have swished past your station while you were still dreaming.

Stereotypes and misconceptions

When I lived in England in the 1960s it bugged me that, when they learned where I was from, people would typically have one of three responses:

1) They had no idea where New Zealand was.

2) They thought it was part of Australia.

3) They knew of it as that pastoral paradise they’d dreamed of emigrating to when they were younger.

Reading my old notes about coming to England in 1962, I realize that I too had huge misconceptions about what my new home would be like. Here is the account of our arrival:

First view of England – not counting faint views through the foggy channel – picturesque houses of Isle of Wight – only we thought it was Southampton and decided England must be charmingly antique and folksy, with church spires peeping through the trees and glowing green fields running down to the sea. but we were a little perturbed that we couldn’t get our geography right. Fascinated by the light – very soft, still a little hazy after the rain and fog of the day before, but with the sun coming through in pale golden streaks.

Our ship anchored off the Isle of Wight and passengers were sent ashore by tender. We managed to miss the boat train by being held up at Customs – a fuss over a lens Tony had bought in New York. But were well looked after by the railway porters, who rushed to get us into a taxi to catch the same train at the central station. On the way, the taxi-driver casually pointed out the old Roman wall of the town. As we gazed in amazement at something 2000 years old, and taken for granted, we began to realize the sense of history about the place, which confirmed even more the feeling of newness about New Zealand. My notes continue:

As the train pulled out of the centre of Southampton we discovered the slums. Obviously not the worst of the slums, but up till then we haven’t really believed that they existed, although we could mention them matter-of-factly. England from New Zealand looked a golden land, a land of opportunities, a land that housed the rich heritage of the old world. It definitely did not mean rows and rows of dreary brick buildings exactly alike, and behind them rows and rows of exactly similar yards, with blackened paling fences and rubbish tins. But occasionally we recognised the cry of a human spirit – from among the debris would rise a patch of golden daffodils dancing in the pale sun, cultivated by loving hands. And for a time we passed through farmland, with pussy-willow growing fat by the railway track, and small boys ambling cheerfully by hedges. Even one or two thatched cottages and barns, and we felt with a sentimental rush that we really were in England. But as we neared London the houses grew thicker and more dreary, their bricks blackened with smoke and soot, their monotony more grey. But even here people were making the best of their situation with window boxes full of bright flowers.

As well as misconceptions, I had opinions. I was amused to find in my notes that, with no knowledge of English social attitudes and no background whatsoever in urban planning, I laid out an argument about high density housing:

I have not yet resolved the problem of what is the best form of high density housing for such a city. Most people are housed in these old row houses, a monotonous block, but at least with some little bit of ground, however filthy and untidy, that they can call their own. The other alternative seems to be tall apartment blocks in their own parks. The disadvantage of these seems to be that the people shifted into them lose their sense of community – they no longer feel that their home is their castle, for they share it and its services with dozens of other families. I would feel the lack of a bit of ground of my own to cultivate, or just sit in. A semi-public park is all very well, but it gives no opportunity for creative contact with the earth. I have seen a few modern blocks of row houses, some of which are quite pleasant, but others will obviously become the future counterparts of the present monstrosities – pleasing to look at now because they are new, but once the newness has worn off little of artistic value will remain. Others, particularly a small block seen near Primrose Hill, had a cheerful friendly atmosphere that appeared more durable.

Ah, the certitude of youth.

The Rain in Spain and all that

In April 1962, fresh off the boat from New Zealand, I stood on a railway platform in Southampton, on England’s south coast. All around me the sound of voices, English voices. In notes written a few days later, and saved in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

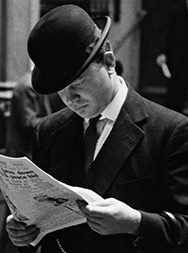

Railway platform – probably much the same as those in NZ, but had a sense of Englishness about it – hard to define, but probably due to the language spoken – correct English accents as if they were the most normal thing – this takes a bit of getting used to. … Here on the Southampton platform we heard the ‘jolly hockey sticks’ manner of speech for the first time. In all cases, it is difficult to distinguish in the mind between the real thing and the caricature which up to now is all we have known. The same with men in bowler hats and umbrellas.

Reading these notes fifty-three years later, I see in them the ambivalences and ambiguities that filled my formative years. Europeans had been in New Zealand for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain, the English, Irish and Scots immigrants brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. For my father and his friends, a man was considered useless unless he was good at working with his hands. An Englishman, especially if he had a “posh” accent, was teased about being a “Pom” and eyed with suspicion until he could prove himself as one of the blokes.

On the other hand, well-spoken Englishwomen dominated the social life of the resort town where I grew up. English bone china teacups clinked in parlors where pictures of thatched cottages might grace the walls, and genteel conversation was made about making the trip “Home” to the old country.

Prejudices about accent can cut both ways. The longer I stayed in England, the more I realized that how one speaks was critically important in that class-bound society. I quickly dropped all the Kiwi slang I ever knew. But, unlike Eliza Doolittle in “My Fair Lady,” I could not get my tongue around the inflections and tonalities that signified “proper” English. My accent slotted me into a pigeonhole labeled Colonial, from which I could escape only by leaving.

Westernesse in the rain

An Aran Island scene on a sunnier day. This aerial photograph by Aongus O’ Flaherty is from http://www.aerarannislands.ie

My first glimpse of the British Isles was the Aran Islands, at the mouth of Galway Bay, where our trans-Atlantic ship stood off to land a few passengers. It was an emotional moment. The destination of our long sea journey at last become visible. Vague romantic dreams faced with reality. I was shocked by the bareness and bleakness of the landscape. Heavy rain was falling, and wind lashed waves onto the shore. The bare rock of the grayish white hills (karst limestone, I later learned) was dotted with tiny scraps of green that glowed brightly in the rain-sodden air. A few white cottages of plain design: four walls and a pitched roof, a door in the middle and small windows at each side.

In notes written at the time, I tried to capture my sense of the place:

Centuries old, yet timeless. Feeling of age and solidity of a way of life that has gone on for centuries – the grimness of it, the few rewards. Can imagine the people to be tough and dour. Weather-beaten faces of seamen who brought the tender out to pick up passengers. No-nonsense faces, with a wry sense of humour.

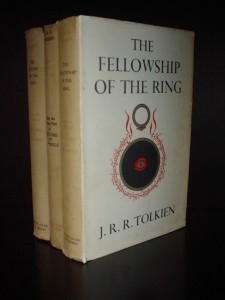

The Lord of the Rings trilogy in its original format as published by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. in the mid-1950s.

From halfway across the world, the reality of the British Isles was also mixed with romantic fantasy. Before we left New Zealand, copies of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the device on its cover of Sauron’s eye within the Ring, surrounded by Elvish script, were passing from hand to hand among our friends. As I looked across the sea to this westernmost part of Ireland, I couldn’t help thinking of Tolkien’s Westernesse, the place to which the fairy people set out when life on Middle Earth became impossible for them.

The curtain of rain swept down again. The ship moved on, headed for Southampton, the end of our journey and the beginning of our new life.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

A Kiwi at the Top

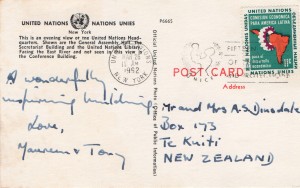

It felt like being in a fairytale. There I was, a country bumpkin on the 37th floor of the United Nations Building in New York, interviewing a man second only to Secretary-General U Thant himself.

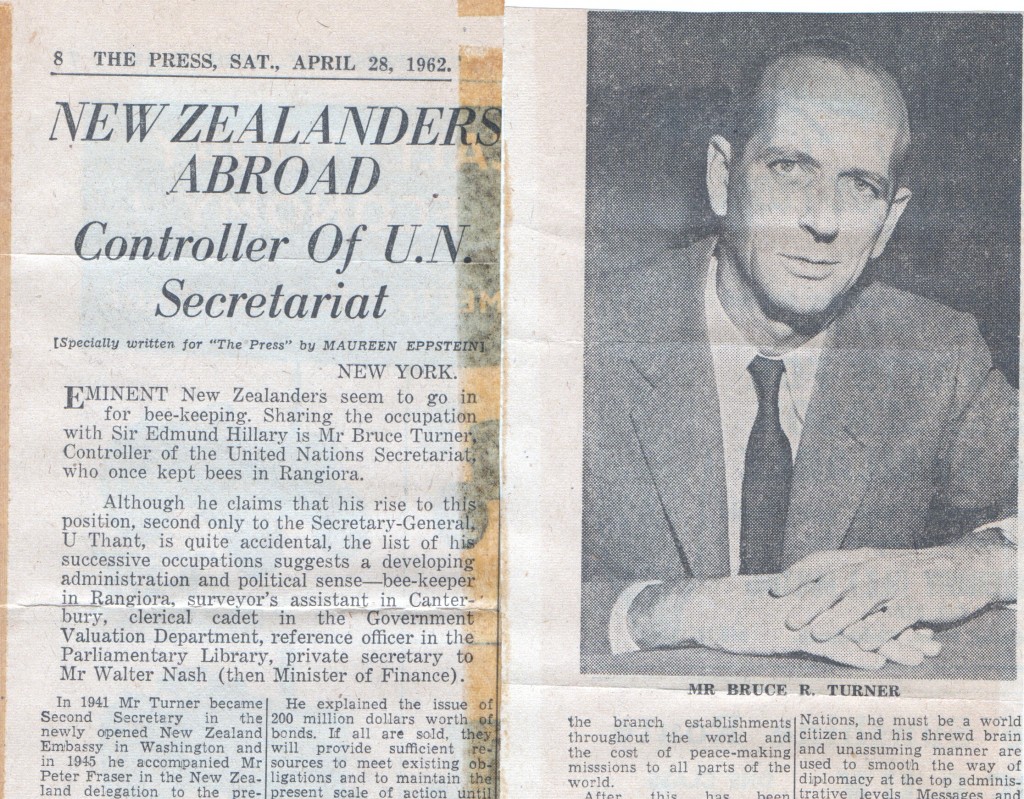

When I left my job at The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, to go abroad in 1962, the paper’s editor handed me a list of names. “These are New Zealanders who have done something interesting with their lives. Track them down and send me back some interviews,” he said.

On the list was Bruce Turner, Controller of the UN Secretariat. In a letter to parents, I described him as “A typical Kiwi c haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

Here’s a transcript of the interview.

1962 Bruce Turner interview

Eminent New Zealanders seem to go in for bee-keeping. Sharing the occupation with Sir Edmund Hillary is Mr Bruce Turner, Controller of the United Nations Secretariat, who once kept bees in Rangiora.

Although he claims that his rise to the position, second only to the Secretary General, U Thant, is quite accidental, the list of his successive occupations suggests a developing administrative and political sense—bee-keeper in Rangiora, surveyor’s assistant in Canterbury, clerical cadet in the Government Valuation Department, reference officer in the Parliamentary Library, private secretary to Mr Walter Nash (then Minister of Finance).

In 1941 Mr Turner became Second Secretary in the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Washington and in 1945 he accompanied Mr Peter Fraser [the NZ Prime Minister] in the New Zealand delegation to the preparatory commission on the first session of the new United Nations.

“Here Mr Fraser had the misguided generosity to lend my services to the first Secretary-General, Trygvie Lie, and I haven’t been able to get out of it ever since,” Mr Turner said recently in New York.

Vast Responsibility

On him rests the responsibility for all financial aspects of the organisation’s activities. “And since everything we do involves money, this means, in effect, the whole lot. The position would be comparable in New Zealand to that of the Treasury, the Auditor-General and in some respects the Public Service Commission, all rolled into one. Sometimes I suspect that I don’t know entirely what the job involves myself,” he said.

His department prepares in advance a budget of regular expenditure. This includes the administration of the secretariat in New York and the branch establishments throughout the world and the cost of peace-making missions to all parts of the world.

After this has been approved by the Administration and Budgetary Committee of the General Assembly, commonly known as the Fifth Committee, the money is collected on a quota system, based on the capacity of each member government of the United Nations to pay. This quota is periodically revised by a committee of ten experts.

But for extraordinary expenditures, such as the United Nations Emergency Force sent to the Middle East in November 1956 and the force sent to the Congo in July, 1960, a separate budget is required, although the proportion borne by each country remains the same.

A Major Problem

Here lies one of Mr Turner’s biggest headaches. Certain countries claim that they have no legal liability for their quota of this extraordinary budget. Meanwhile, funds are running low, but the need for maintaining forces in the Congo continues.

He explained the issue of 200 million dollars worth of bonds. If all are sold, they will provide sufficient resources to meet existing obligations and to maintain the present scale of action until the end of 1963.

Mr Turner put the problem in the smoothly rounded language of diplomacy and press statements: “On the success of this bond issue depends the future of the whole organisation and its peace-keeping operations.” He broke off to joke grimly: “Oh well, if it fails, this place will be blown up and I will be out of a job.”

He spread his hands lightly round the pleasant wood-panelled room with its quiet beige and jade upholstery. Heavy curtains hid a view of the East River and Brooklyn in the early evening. On a low table, beside a bowl of spring flowers, a handsome Maori carving gave a hint of the occupant’s country of origin.

“Some day I might retire to New Zealand—that would be the normal procedure for any expatriate New Zealanders,” he said. “It would be somewhere with a warm, mild climate. Tauranga perhaps—that is not too far from my friend in Hamilton who owns a brewery.”

Meanwhile, like all other employees of the United Nations, he must be a world citizen and his shrewd brain and unassuming manner are used to smooth the way of diplomacy at the top administrative levels. Messages and telephone calls continued to pour into his office, telling of Government decisions on the bond issue. The maintenance of forces in the Congo, while still a grave problem, seemed a little more hopeful.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Art stuns like a hammer blow

With gold velvet drapery as backdrop, the newly acquired Rembrandt, “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,” stood on an easel in the foyer of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Spotlights accentuated the golden glow of the painting’s surface. As I gazed, I felt a resonance with the feelings of the person depicted, my thoughts drawn into his as if into a dizzying vortex. I was astounded that brushstrokes and pigment could have such power to move me.

I had not seen great art before, except in books of reproductions. I had devoured the collection of large format books in my high school art room, and spent hours browsing the art section of secondhand book shops when I was in college. When we left New Zealand in 1962, Tony and I had as a priority to visit art museums and see the work of artists we admired. But nothing had prepared us for being in the presence of the real thing. Upstairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art we found a whole room of Rembrandts. Dancing down a broad staircase, a whole series of bronze sculptures by Edgar Degas. We saw so many great works we discovered the phenomenon we named “mental indigestion” and wished we had more time in the city so that we could come back. We knew it would take weeks, months even, to absorb all this museum had to offer.

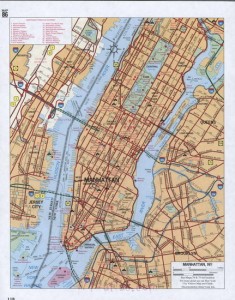

We visited other art museums during this stopover in New York on our way to England. Some we loved, some less so. In a letter to parents I wrote: “Sunday afternoon we went out to The Cloisters, which is right up at the northern tip of Manhattan. This is a religious museum. Parts of the remains of many old churches of Europe have been brought across and incorporated into the present structure, which keeps as closely as possible to the original styles. In a sense it is a success – some of the old fragments of stonework are very fine, and there are some very fine paintings, altar ornaments, and some magnificent tapestries – the highlight of the whole exhibition. But in spite of their attempts to reproduce chapels, all sense of reverence has been lost – the things are a curiousity for the locals to gawp at, and even sacrilegious.”

As I look back on these youthful letters and these memories, I see opinions about what matters to me already forming and clarifying. Many more experiences of the power of art would come in future years: sitting on a bench in a crowded London gallery, weeping over Georges Rouault’s “The Old King;” gazing in awe at the rose window in Chartres Cathedral; feeling the silence of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Always, enriching these experiences, the memory of that stunning awakening in New York.

Country bumpkins in New York

The friends we were traveling with chose the hotel, the cheapest they could find. It was on W. 46th Street, just off Times Square. Only one thin hand towel in the grungy bathroom. What to do? We called the desk. A maid appeared, to tell us the towels were not yet back from the laundry. In hindsight, a tip might have made towels magically appear. But we knew nothing about tipping; it wasn’t a part of the culture we knew.

Breaking our 1962 journey from New Zealand to England as young married couple off to see the world, Tony and I had disembarked in New York to visit my sister Evelyn, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University in upstate New York. From there the three of us traveled by Greyhound bus to Baltimore to spend a few days with her friends Brian and Jennifer Wybourne and visit Washington, DC.

Driving with the Wybournes back to New York, where we were to board another ship bound for England, we were wide-eyed at our first glimpse of the New Jersey turnpike. In a letter to parents I wrote: “…one of the most famous of the turnpikes – 150 miles of unhindered 6-lane highway. Then navigating the streets of the city – practically all are one-way, which makes it complicated, and you can imagine the traffic.”

The letter continues: “The next morning we went up to the top of the Empire State building – early, before the mist got up. The view from the top is terrific – you can see the whole extent of New York city – which is saying something.” I look back in memory and see the young woman I was, neck stiff from craning upward at rows of skyscrapers that made deep canyons of the streets, mind agog at the level of luxury displayed in store windows. I remember wandering through several of the huge department stores, feeling lost and out of place.

One day we walked to the tip of Manhattan and back, excited to see Wall St. and Greenwich Village, and to walk on Broadway. I wrote: “We were really footsore by the time we reached the hotel, but then we had the big experience of our trip – riding the New York subway during rush hour. That was some experience. We held each other tightly, and shoved with the rest. Sardines in a can had nothing on the train – but you had to make sure you weren’t pulled out with the rush at each station.” Evelyn, who was taking us out to the Bronx to dinner with the family she was staying with, wrote in her letter home: “I deliberately engineered it to be at Grand Central Station about 5 past 5 at night. It was quite an eye-opener for them…”

On each of the other nights we had the new experience of dining in a restaurant of a different nationality, all quite cheap by New York standards, and all in the same block as the hotel – Greek, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, as well as American – hamburgers and doughnuts.

For lunch Evelyn introduced us to automats. I commented: “We found foreign food much more interesting than American – they process it and vitaminise it, and goodness knows what – the result is rather tasteless.”

In future weeks I’ll talk about other aspect of our first visit to New York: the art, the music, the experience of visiting the heart of the United Nations secretariat.

And yes, a few more threadbare towels did eventually show up in our hotel room.

Other people’s weather

An ethereal music filled the air as Tony and I stepped down from the Greyhound bus at Niagara Falls in March 1962, a music so sweet and high it seemed to come from some magical place. I gazed about me. Nothing but bare trees and an almost empty parking lot. A wind that stung my ears. Then I saw them: icicles, many inches long, hanging from every twig and tinkling against each other with every gust.

Growing up in the subtropical north of New Zealand, I did not see snow until I was an adult. Our winters had heavy rain and an occasional frost, enough to whiten the grass and form thin sheets of ice on puddles. But nothing like this: the gigantic falls themselves half frozen and the temperature the coldest I had ever known. Historical records tell me it was probably about 30°F. (though the wind chill factor would have made it seem colder), and that the winter was pretty much a normal one.

We had broken our journey from New Zealand to England in New York to visit my elder sister, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University. As we rode the Greyhound bus upstate to Syracuse, what fascinated me as much as the landmarks my sister pointed out were the piles of dirty snow everywhere. I began to comprehend the northern hemisphere stories I had grown up with, where winter was a time of death and darkness, the weather something to be feared, and the spring thaw a time of great rejoicing.

Having recently passed through the tropical miasmas of Panama, I was also discovering that people could learn to live in places where the climate was not friendly, though the strategies they used to deal with the climate sometimes left us puzzled. In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for example, where our ship had berthed for a day on its way to New York, we were stunned by the difference between the searing heat outdoors and the air-conditioned iciness inside the big stores.

Tony and I realized then that that we were just starting on the great adventure of learning how the rest of the world lives.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes