Archive for the ‘history’ Category

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

What place have we come to?

I grew up in a country with strict gun control laws. In New Zealand in the 1940s and ‘50s, you needed a permit and a “proper and sufficient purpose” to acquire a firearm, and all weapons had to be licensed and registered. Automatic pistols were outlawed altogether. My dad kept a rifle in a locked closet, taking it out occasionally to go hunting for feral pigs with his friends. But guns were not part of my small town landscape. Even today, New Zealand police officers do not routinely carry firearms.

Imagine my state of mind then, when the newspapers of my newly adopted country ran daily news stories about firearm-related deaths. Looking back now at government statistics, I see that in 1968 the US, with a population of 200.7 million, had about 31,400 firearm deaths. (Since the Center for Disease Control bundled multiple years 1968-1980, this is an average.) CDC, in a 1994 report, predicted that people killed by firearms would by 2003 outnumber vehicle crash-related deaths. Louis Jacobson, in a PunditFact article, verifies Nicholas Kristof’s 2015 statement that “More Americans have died from guns in the United States since 1968 than on battlefields of all the wars in American history.”

On April 4, 1968, our family had been in the US less than a year. My husband Tony was in Washington, DC for an international magnetics conference. On March 30 I wrote to my parents: He is very excited about this, especially as he hopes to meet some of his friends from England who are expected there.

About a week later I wrote again:

10 April 1968

Tony also got involved last week in America’s other big trauma – the race riots following Dr. King’s assassination. He had great difficulty getting out of Washington on Friday [April 5], but fortunately the flight crew of his plane had the same problem, so managed to catch his correct flight a couple of hours late. I gather that the conference was very successful and useful, if somewhat exhausting.

Reading these words again today, I notice the calm, distancing tone. I couldn’t tell my parents that I was terrified. Tony had described to me the view from the night sky: cities in flames all across America.

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was fatally shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, shortly after winning the California presidential primaries in the 1968 election.

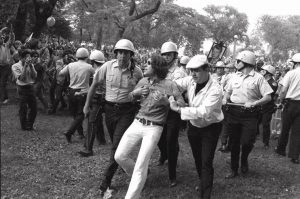

Police lead a demonstrator from Grant Park during demonstrations that disrupted the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968. (AP) Image from https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Yet more public and political mayhem was to come. In August we endured reports of the violent clashes between police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. In its report Rights in Conflict (better known as the Walker Report), the Chicago Study Team that investigated the incident stated that the police response was characterized by:

…unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night. That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring.

I have to agree with Haynes Johnson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who was covering the convention. He wrote in a 2013 Smithsonian Magazine story that the convention was

…a lacerating event, a distillation of a year of heartbreak, assassinations, riots and a breakdown in law and order that made it seem as if the country were coming apart.

Summer of 1967: an immigrant’s view

San Francisco, 1967. Sunday afternoon at Maritime Park. About twenty young black men sit on a low sea wall, bongo drums between their knees, thrumming an intoxicating rhythm. A crowd has gathered. Picnicking on the beach, my husband, children and I listen too, enthralled by the joyous sound. We have spent the morning exploring the old ships at the Hyde Street pier. Later in the day we explore the new tourist attraction of Ghiradelli Square.

In a letter to parents I wrote: … an old chocolate factory now converted into an arty plaza and shopping centre with fountains, outdoor restaurants, etc. … One of the most interesting places was the Children’s Art Centre – just a little gallery for exhibitions of children’s paintings, and free paper and crayons for any infant who felt like drifting in and drawing a bit.

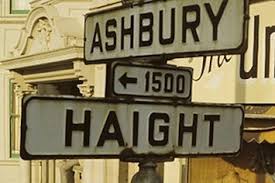

New to California, we had heard of the hippies in the Haight/Ashbury district, so on our way home to Cupertino we detoured along Haight Street. Sure enough, we passed storefronts with funky signage, long-skirted young women with hair held by braided headbands, long-haired and bearded young men in tie-dyed tee-shirts, a group playing music on a corner. Like travelers viewing exotic fauna, we gawked and drove on.

It is only now, looking back, I realize how little we understood of what we were seeing. The flower children who poured into San Francisco in what is now known as the Summer of Love were an eclectic group, revolutionary in their rejection of consumerist values, opposition to the Vietnam war, and embrace of free love, drugs, art and music. But this counterculture had a historical context, and this as immigrants we did not possess. I remember where I was when I learned in 1963 that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Like my English neighbors, I was shocked. But I did not experience that communal sharing of grief my American contemporaries remember. On British television I saw newsreel images of civil rights marchers being attacked by snarling dogs, fire hoses, and baton-wielding cops. But that was in some barbaric, far-off country. From the BBC news reports about Vietnam, it was obvious that American military involvement was a disaster, bound to fail as the French had before them. I’d not yet grasped the deadly impact of the draft on young American men.

Over the decades that followed our first summer in the US, I gradually filled in my knowledge gaps, mainly through snippets of personal information: a teacher who dodged the draft by moving to Canada, a veteran who came back from the war physically and psychologically maimed, a man who as a student registered voters in the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, a doctor and his poet wife who were cast out of their New England village because of their opposition to the Vietnam war. I took part in fair housing studies, and learned first-hand the effects of racism. I read histories of the period. But there has always been for me a sense of distance, a sense of being an outsider when my contemporaries discuss the experiences of their youth. I believe this sense of distance is true of all immigrants who come to this country as adults. Try as we might to ‘become Americans,’ we simply cannot share in the memory of those collective experiences that have shaped the early lives of our American-born neighbors and friends.

However, it has been fifty years since our arrival as new immigrants, since that summer of 1967. Over the years, new national crises and issues have unfolded. We have reacted to them, talked about them with friends, shared in community actions. We learned to belong. We too have finally become part of the American story.

They paved paradise

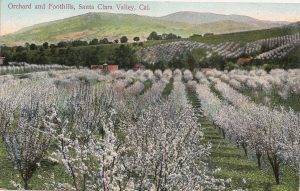

Golden fruit clings to leafy branches. Golden-skinned men climb orchard ladders, old metal harvesting pails in hand. Close to the road, a huge billboard: FOR SALE FOR COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT. The scene has stayed in my mind, my first introduction to the landscape of my new home.

I moved, with husband and children, to Cupertino, in Santa Clara County, California, in late May of 1967, just as the apricot harvest was beginning. Between our apartment, off N. Blaney Ave. by Interstate 280, and the nearest food market, on Stevens Creek Blvd., was a mile of apricot orchards. In other directions were acres of cherries, almonds and prunes. The Santa Clara Valley, a fertile alluvial plain, was until the 1960s the largest fruit production and packing region in the world. The beauty of all that spring blossom gave rise to the nickname “Valley of Heart’s Delight.”

The post-World War II economic boom and the rise of high-tech industry changed all that. My husband and I were part of a flood of new arrivals that forced out the fruit farmers and replaced orchards with tract houses, shopping centers, and business parks. It was a bittersweet time. On the one hand the energy and excitement of the new technological advances, the sense of living where the future started. On the other, sadness at the destruction of all those beautiful trees. Among my old notes I found a few lines of a poem I wrote in those early years:

The field is bare now where the orchard stood.

Apartment builders hammer at its brink.

How soon do we evict the meadowlarks

that saunter golden in the rainy dusk,

foraging through weeds by the highway’s edge?

In recent decades, with the growth of the environmental movement, there grew a collective sense that something important was being lost. Efforts were made to preserve at least the memory of that fruitful landscape. In 1994, the City of Sunnyvale preserved ten acres of Blenheim apricot trees “to celebrate the important contribution of orchards to the early development of the local economy” and created an interpretive museum beside it.

The Olson family, whose 100-acre cherry orchard was one of the last vestiges of cherry farming in the area, still retains a few acres of trees and the roadside fruit stand that began in 1899. Owner Deborah Olson commented: “We try to educate people just moving in to the area, who don’t know what it’s all about. They get a sense of place, about how it began here, and they kind of feel a part of the community.”

Blogger Lisa Prince Newman, whose family also moved to the valley in the 1960s, is collecting stories, pictures and apricot recipes from the few farming families still in the valley.

The chorus of Joni Mitchell’s song “Big Yellow Taxi,” written in the late 1960s, sums up the sense of profound loss:

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Hear Joni sing “Big Yellow Taxi”

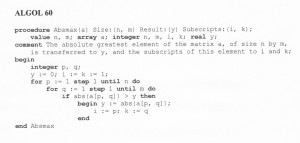

When programming was a women’s job

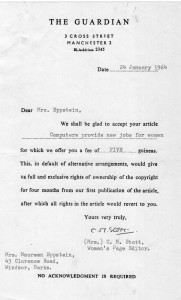

Back in the day when computer programming as a profession was so new it lacked a gender bias and could well have become a female specialty, I wrote an article about a woman programmer which helped launch a successful freelance business staffed almost entirely by stay-at-home mothers. For me too, it was a big breakthrough: the story was published by the Guardian newspaper on 31 Jan. 1964 under the headline “Computers provide new jobs for women.”

I first met Stephanie (Steve) Shirley in 1963, when our same-age babies were tiny. We had a pleasant chat about what intellectually stimulating work programming was. Frustrated with the sexism that prevailed in the world of employment, Steve had left her job with Computer Developments, Ltd., to start her own company, Freelance Programmers. Her workload was growing as new clients learned of her services, and she was starting to reach out to other former programmers for help.

In a letter to parents a week after the article was published, I wrote:

… My article was published in the Guardian, and since then I have had a flood of letters. Mainly for forwarding to the woman mentioned in it, a computer programmer, retired with a baby the same age as ours, who is trying to get other women like herself to join her in working on a free lance basis.

Less than a year after my first article, the Guardian published my follow-up. Freelance Programming Ltd. was launched. Over time it grew to 8,000 employees, and Dame Stephanie Shirley is now recognized as a pioneer of the British information technology industry. Here’s the follow-up article:

Computer women

In January of this year Mrs Steve Shirley was working quietly at home making up computer programmes in between caring for her baby and doing her housework. Now she has found herself the head of a company employing upward of twenty retired, home-bound programmers like herself. Like many businesses, it started in a very small way. When she retired from her job as a programmer with a big computer company, she was offered a few programming projects to keep her occupied at home. She could work at them in a leisurely fashion, enjoying the contrast between the stark, modern, technical world of computers and the idyllic charm of her cottage in the Chilterns. In this way she found a mental satisfaction that had not been fully achieved in caring for her home and family.

As her circle of clients widened, she was considering seeking out other retired programmers like herself who could help with the load of work. Then a Guardian article on programming as a career for women [my first article] brought in a flood of letters from women who were desperately needing something more stimulating to do with their time. Many were very highly qualified, but because of their children could not consider going back to a job that wanted them on an all-or-nothing basis.

There are some obvious difficulties in running a part-time business of this kind, and Freelance Programmers Ltd. is now having to face some of them. The first is one of organisation. To get a reasonable standard of efficiency, Mrs Shirley had to eliminate those applicants who did not have access to a telephone. The business is at present being run from the cottage, where the telephone rings at all hours of the day and night, and Mrs Shirley herself works very long hours keeping in touch with her staff. In order to get back herself to the part-time basis which would give her time for her family, she plans to open a central office. Here she would be able to employ a typist—at present she does the typing herself, or sends it out to one of her staff, thus making a two-day time lag. The office will be in an area where some of the staff are already living, and her plans are for a combined office and nursery suite, so that the mothers who come to the office will have the children cared for, but will be at hand if needed.

There will still be many of the staff working by themselves at home. Some of them are doing it because they need the money, but for the great majority it is a release from the pressure of four walls and a roof and a tedious round of housework. Mrs Shirley has proved that this method can be made to work, particularly for fairly short-term projects. A larger job, that might take perhaps two years to complete, she prefers to give to women less tied to family responsibilities.

She also needs more free women for the large amount of travelling and meeting clients involved in the business. An ideal staff member is a woman with no children, who is married to a schoolteacher. She had been unable to get a normal job because she wanted all the school holidays off to be with her husband, and not just the regulation three weeks. But for several months at a stretch she is free to go anywhere, do anything for the company.

It has become clear that an entirely homebound, part-time organisation will not work satisfactorily. But a group that is basically of this sort, with a leavening of more mobile staff and with an efficient central organisation, may well be a model on which similar groups of professionally trained women might be based.

Ducks and swans and boats, oh my!

My son’s first word was “duck.” This is not surprising. We lived in Windsor, England, downhill from Windsor Castle and a few blocks from the River Thames, a destination for our daily walk.

There was always something to see on the river. Sometimes rowing crews from Eton College, eight oarsmen in a long narrow shell sweeping the water with long strokes, the cox calling the rhythm. Lots of boats. My family’s special favorite was the elegant “Esperanza,” one of the many riverboats that took visitors on trips upriver.

David’s favorites were the ducks. There were hundreds of them on the river, dabbling among the water weeds, bobbing under with their tails in the air, or clustered enthusiastically close to the walkway if we remembered to bring stale bread to throw to them.

The swans were more scary. They were big, and their large beaks looked ready to take a nip if they were feeling feisty.

The swans of course are famous. Some of the mute swans on the Thames belong to the Queen, others to two ancient guilds, the Vintners and the Dyers. Each year, toward the end of July, there occurs a ceremony called Swan Upping, during which Thames swans with cygnets are rounded up by official Swan Uppers, caught, checked for health, marked with the appropriate leg rings, and then released under the direction of the Swan Marker.

Swan Upper with swan. Photo by Bill Tyne, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29175336

Every day, something new to see.

A Shakespearean ghost and an old tree

Herne’s Oak, Windsor Park circa 1799

Etching with hand colouring, attributed to Samuel Ireland (1744-1800). The two Merry Wives of Windsor, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford, are standing with Falstaff at Herne’s Oak.

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

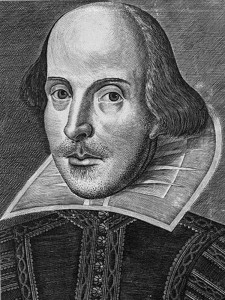

In the grounds of Windsor Castle in England stand thousand-year-old oaks so huge and gnarled and blasted it’s easy to imagine them haunted by spirits. Shakespeare used this conceit in his play “The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

When I was a Windsor wife in the early 1960s , I attended a performance by the Windsor Repertory Theatre of “Merry Wives” one summer evening in the castle gardens. Probably written to amuse Queen Elizabeth I, the play uses as its setting then-familiar Windsor landmarks, such as the 14th century Garter Inn on High Street and Herne’s Oak in Windsor Great Park.

The play centers around the drinker and gambler Sir John Falstaff, known from the plays Henry IV part 1 and part 2. Short of money, he comes to Windsor where he attempts to seduce both Mistress Page and Mistress Ford in hope that at least one of them will share her husband’s wealth with him. He writes each wife an identical letter, but the two women, who are close friends, immediately show each other their letters and are outraged.

The wives decide to teach Falstaff a lesson, and pretend to lead him on while planning his downfall. He is dumped from a laundry basket into the muddy River Thames, and beaten while disguised as the Old Woman of Brentford, who is believed to be a witch. With their husbands in on the secret, they concoct a final revenge for his clumsy insults to their virtue. Mistress Page sets the scene:

There is an old tale goes that Herne the hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv’d, and did deliver to our age,

This tale of Herne the hunter for a truth.

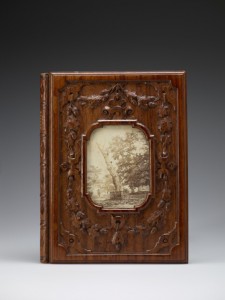

Cover of William Perry’s “A Treatise on the Identity of Herne’s Oak, Shewing the Maiden Tree to Have Been the Real One”

Probably presented to Queen Victoria by William Perry, c. 1867

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

The Royal Collection website notes:

Perry’s treatise claiming the authenticity of this tree echoed Queen Victoria’s own belief, though his view was not entirely unbiased since he had been given portions of the wood to carve into souvenirs, which include the binding of this book. A photograph of the tree shortly before its fall is inserted in the front board.

Falstaff is induced to dress as the ghost of Herne the Hunter and wait for the two women at Herne’s Oak, where he is pinched and tormented by local children dressed up as fairies.

Since Herne’s Oak has now fallen, exactly which tree it was—the one that fell in 1799 or the one in 1863—remains in dispute. Also unclear and undocumented are the origins of the myths about Herne the Hunter. Shakespeare was the first writer to mention him. His purported connection to ancient archetypes representing the primal power of nature may be an artifact of Victorian story-makers. Some evidence suggests there was a real game-keeper in Windsor Great Park named Herne or Horne, possibly in Elizabeth I’s time, possibly earlier, who, having committed some great offence for which he feared a dreadful punishment, hanged himself on an oak tree. Maybe Mistress Page had it right: the memory of such an event at a scary-looking tree could be enough to start a legend about a ghost.

What I learned at Stanford

The New Zealand high school I went to, Tauranga College, recently celebrated its 70th anniversary and hosted a reunion for those who attended the college before 1957, the year it split into two single-sex schools. I was one of four alums invited to give a five-minute talk on some aspect of our lives. I was in prestigious company: an emeritus professor of chemistry, the manager of New Zealand’s cricket team during many of its World Series tours, and a researcher doing impressive work in health economics. I chose to talk about my 20 years as an administrative writer and editor at Stanford University, a relatively low-level job, but one in which I had considerable personal satisfaction.

Later that day, many women came up to me to tell me how much they appreciated my words. “I felt affirmed,” one woman said. Our generation was taught rather firmly that a woman’s role in life was to marry and take care of husband and children. Many of course took on paying jobs and volunteer work, but “women’s work” was not highly valued in that strongly patriarchal society.

Here’s the text of my talk:

What I learned at Stanford

I’m sure most of you have heard of Stanford University. The name might bring to mind words like Silicon Valley, medical breakthroughs, prestigious think tank. There’s another, less visible part of the story: the staff work that keeps the university going.

I’m still amazed at how I found myself there in 1979. I was easing back into the job market after being a home-maker and struggling freelance writer. At a neighborhood gathering, I learned that the Stanford administration had a crisis. The federal government was changing the rules for how to calculate the indirect costs for research contracts and grants. (For instance, how much of the university’s electricity cost can reasonably be charged against a particular contract.) When the finance department and the research department put together task forces to figure out how to implement the new rules, they discovered that the faculty doing the research had no idea what the accountants were talking about. They needed someone to translate accounting-ese into English. Could I do it? my neighbor, a Stanford professor, asked. At that time my accounting knowledge was zilch. But what I did have, as a journalist, was the ability to ask the dumb questions that would get me a highly technical story in everyday language. So I was taken on, and within a couple of weeks was ghost-writing memos for the Controller and the Dean of Research.

I stayed at Stanford for twenty years, working on projects related to administrative systems and policies, and support networks for department administrators. During that time, Stanford administration was going through a sometimes painful transition to the world of computers. Imagine if you will a dark basement in an old stone building. Rows of desks are filled with elderly women, most of whom have been there forever, processing Accounts Payable by hand. They’ve never touched a computer, and they’re terrified.

I was part of a group doing our best to help ease this transition. For instance, when I became editor of Stanford’s annual financial report, the entire $450 million of income and expenditures was typed up and tallied by hand. I brought in someone familiar with a computer spreadsheet program to reduce the manual labor. As editor of administrative policies, I headed up an Information Technology skunk works to fulfill a dream of making all the university’s policy and procedure documentation available online. (This was in the early 1990s, before the World Wide Web took off.) I also designed and implemented support programs to gently persuade computer-phobic department administrators to give up their paper copies and use the new system. These programs were the topic of papers that I presented at national conferences.

Sometimes I would ask myself: Does anyone really understand how much power I have? How is it that I, a relatively low level administrative analyst and editor, am dictating annual report deadlines to Stanford’s prestigious external auditors, or leaning on vice-presidents to update their policies, or even writing the policies for them?

The answer is that there are two kinds of power. One is hierarchical: you’re the boss, so you have the right to tell those under you what to do. The other kind of power is interpersonal: if people trust and respect you, they will willingly help you implement a common goal. I learned at Stanford that trust and respect are really all that matter.

A nuclear protest in the rain

Participants in the 1963 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament march from London to the nuclear weapons facility at Aldermaston in Windsor High Street. Image by Tony Eppstein.

To walk from London to the UK’s Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in Berkshire takes four days. Starting in 1958, the year the UK and the US signed a mutual defense agreement “on the uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defense Purposes” tens of thousands of people did it over Easter weekend each year, to protest the risks to humankind and to the earth itself from the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

I first watched the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s march on Easter Saturday, 1963. Heavily pregnant, I stood with other townsfolk on the sidewalk of Windsor High Street. Rain had fallen all week and continued to fall, a cold, relentless, English rain. About mid-morning the first marchers came, under a sky the same brooding gray as the rain-soaked castle walls above us. Their clothes sodden, they chanted fitfully to the dogged drumbeat of wet shoes on streaming pavement. Some carried banners bearing the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament symbol.

We had a friend in the march. An hour passed before we spotted him, poncho flapping, wet hair plastered to his face. We cheered and called out. He grinned and waved. Another hour or more before the last stragglers passed through the town. We cheered them too. I leaned on my husband’s arm, feeling the weight of the unborn life inside me.

Postscript: organized protests against nuclear weapons in the UK continue to this day. You can see an overview at the Action AWE website.

Good old days at the post office

In December of 1962, before there were mail codes or mechanical sorters, I worked for a week at the post office in Windsor, England, helping with the Christmas rush. I mentioned it in letters to parents:

18 Dec. 1962

…Hope this reaches you in time for Christmas – along with the other thousands of tons of mail being posted this week. I know – I have to sort the stuff. I am spending the week working in the sorting room at the post office. Very difficult job! – turning the stamps up the right way as the letters come out of the postbags. Have to work pretty hard, but it’s rather fun – very cheerful, friendly crowd – and good money.

26 Dec. 1962

…I had a very interesting week in the Post Office. Halfway through the week I was promoted to sorting, which was a bit more fun, though harder work than facing up.

Those were the days, before email, Facebook, Twitter and other social media, when the annual holiday greeting card was how one kept in touch with extended family and friends. According to Wikipedia the custom of sending greeting cards has a long history, dating back to the ancient Chinese. The postage stamp was introduced in England in 1840. Cards started being mass produced by the 1850s. From then on, mailboxes became crammed each December with penned good wishes.

Every card and letter had to be sorted by hand. Mechanical sorting, which depended on reducing the address to a machine-readable form, came in a few years after my stint at the Windsor post office: the 5-digit ZIP code was introduced in the U.S. in 1963, and England’s alphanumeric postcode system in 1966.

Communication methods have changed, and fewer greetings now go by “snail mail.” The U.S. Postal Service reports that First-Class Single Piece Mail; that is, mail bearing postage stamps, such as bill payments, personal correspondence, cards and letters, etc., declined by 47 percent in the decade 2005–2014. But that urge to reach out to those we love during the holiday season is still with us.